Medicare Change a ‘Huge, Significant Thing’ for Alabama

It’s about noon on a recent Thursday in Sylacauga. Local resident Phyllis Caudle just arrived at Coosa Valley Medical Center to have lunch with her sister.

“We eat here every day!” Caudle says.

The hospital’s cafe regularly draws a big crowd, according to Vanessa Green, Coosa Valley’s chief development officer. Green says the hospital also operates a popular catering service out of the cafe. While it may sound a little odd, she says it helps engage with the community and it’s successful.

“We do whatever we need to do around here to make it work and to make it happen,” Green says.

These days, rural hospitals in Alabama have to get creative. Danne Howard, chief policy officer with the Alabama Hospital Association (AHA), says it’s increasingly difficult to make ends meet. Many rural hospitals have had to freeze or cut salaries. Some have eliminated services, like obstetrics and gynecology. Howard says others partner with outside groups or bigger health systems to take some of the financial pressure off.

“It’s clear to see that we’ve got a number of hospitals that may not survive in the current financial environment,” she says.

In the past decade, seven rural hospitals have closed in Alabama, and of those that remain, 88% operate in the red.

But Howard says Medicare is throwing the state a lifeline. The federal health insurance program, primarily for senior citizens, recently approved a plan to start paying rural hospitals a little more money.

“Fundamentally it is a Flawed System”

Glenn Sisk, CEO of Coosa Valley Medical Center, says it’s a step in the right direction. Medicare covers about 50% of patients at Coosa Valley, which is typical in rural areas. But Sisk says it also creates a significant financial challenge.

“Rural Alabama hospitals have the lowest reimbursement from Medicare of any hospital in the United States,” Sisk says.

Medicare uses a complicated formula, called the Wage Index, to determine reimbursement rates across the country. It is based on the idea that salaries are higher in certain states and bigger cities, so hospitals in those areas receive more money for the same services. For example, Medicare might pay a rural Alabama hospital $4,000 for treating a patient with pneumonia, but it pays an urban one in California $6,000 for the same treatment.

“The rich get richer and the poor get poorer,” Sisk says. “So fundamentally it is a flawed system that makes absolutely no sense.”

Industry leaders and academics across the country have long criticized the Wage Index. In a meeting with reporters last month, Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), called the formula an example of the “distortions in Medicare policy” and a strain on the nation’s rural hospitals.

That mounting pressure has led to change. Starting next month, Medicare reimbursement rates will increase for hospitals in the bottom 25%, which includes just about all hospitals in Alabama. Danne Howard with AHA has been advocating for the move for decades.

“This is the first time any steps have actually been taken to recognize that disparity and to start looking at ways that we can address it,” she says.

Not the Final Fix

Howard says the new Wage Index formula, which will be in place for four years, is expected to bring in an additional $38 million dollars for the state during the first fiscal year. But hospitals in Alabama will still get reimbursed much less than in states such as California or Massachusetts. And Howard says health care providers face other challenges.

“This is a huge significant thing for Alabama,” she says. “It’s not however the final fix.”

She says hospitals will continue to spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year caring for patients who fall into the coverage gap — people who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but don’t make enough to qualify for Affordable Care Act Marketplace premium tax credits or subsidies.

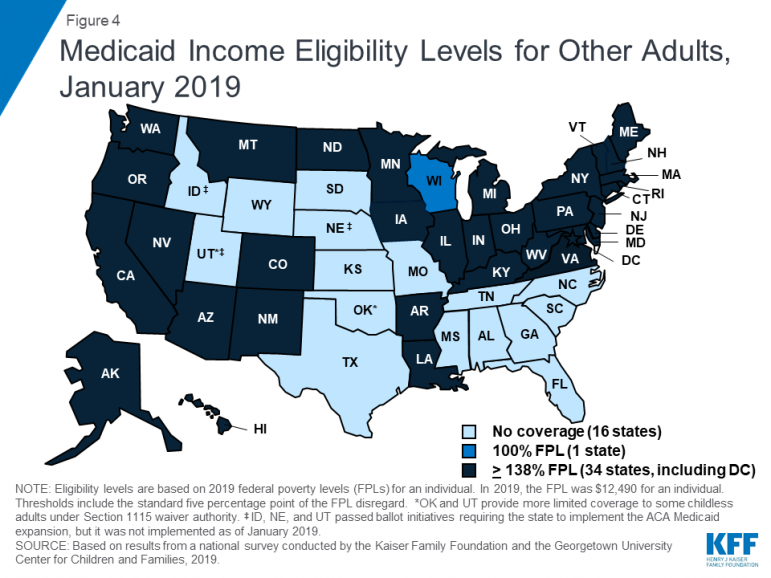

Alabama has among the strictest Medicaid eligibility requirements in the nation. To qualify, adults with at least one child must earn less than $3,839 a year, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Adults without children or a disability do not qualify.

Howard and hospital leaders across the state continue to advocate for Medicaid expansion, which would extend coverage to parents and other adults who earn up to 138% of the federal poverty level. Alabama remains one of 13 states that refuses to expand. A recent study projects expansion would yield an $11.4 billion economic impact statewide over a four-year period.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

A new film follows Paul McCartney’s 2nd act after The Beatles’ breakup

While previous documentaries captured the frenzy of Beatlemania, Man on the Run focuses on McCartney in the years between the band's breakup and John Lennon's death.

An aspiring dancer. A wealthy benefactor. And ‘Dreams’ turned to nightmare

A new psychological drama from Mexican filmmaker Michel Franco centers on the torrid affair between a wealthy San Francisco philanthropist and an undocumented immigrant who aspires to be a dancer.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.