School Funding In Alabama: A View From Sumter County

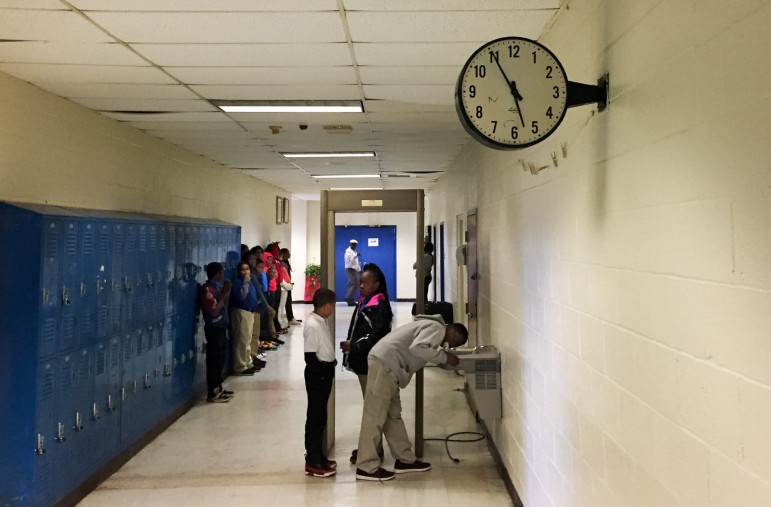

The front door at Livingston Junior High in rural Sumter County is something of an early warning system. It screeches so loudly that visitors can hear it — from the parking lot. Once inside, the scale of disrepair becomes clear.

“In the girls restroom, they may have four or five stalls, but only one works,” says principal Tramene Maye, giving a quick walking tour. “And the funds are limited, so what do you deem necessary? If one is working, that’s what you’re going to allow to continue.”

And Livingston’s problems don’t end with a loud door and broken toilets. One former classroom leaks when it rains. Garbage cans catch some of the water, but the moldy smell and buckled floor prove they miss plenty. Around the school, it’s a similar story: broken windows, peeling paint, cracked floor tiles. Maye insists there just isn’t enough money to fix it all.

“We have 580 students. Everything should be functioning,” Maye says. “When you have to spread that money thin like that, it’s hard to put it in the right places. But we do the best we can.”

Sumter Central High senior and star student Jewel Townsend’s school is in better shape than Livingston, but she says it’s still hard when she travels to schools and sports facilities outside the district.

“I see that Sumter County doesn’t have that,” she says, her voice catching. “It’s like, ‘Wow, really? Why can’t we have that?’”

This largely low-income, all black school district doesn’t have a baseball or soccer team. And, says superintendent Tyrone Yarbrough, “we would love to have music and art in all of our schools. We don’t have that. If we had us some kids who were interested in, say, orchestra … we don’t have that.”

In more affluent districts, local property tax revenue makes a big difference for schools. But in rural Sumter, which is mostly farms and timberland, there isn’t much to tax. It’s also hard to raise rates on what is there.

In Alabama, local voters have final say on tax hikes. Sumter school supporters have tried and failed twice in recent years to raise local rates. While some states send extra need-based dollars to districts like Sumter that serve lots of disadvantaged students, Alabama does not.

Sumter County school board member Julene Delaine says Sumter schools have another challenge. While basically all of their students are African-American, roughly a quarter of the county’s population is white.

“They live in this county, but they will not send their children to the schools in this county,” Delaine says. Instead, many white families send their kids to a local private academy or outside the area. “We shop in the same place. We eat at the same restaurant. So why can’t our kids go to school together?”

In a 2011 lawsuit that literally put centuries of Alabama history on trial, plaintiffs from Sumter and another county tried to prove the state’s school-funding system – with its uniquely low tax revenue from farms and timberland, and its political hurdles to raising local taxes – has always been racially discriminatory.

The federal judge excoriated the system in an 800-page opinion but ultimately found the plaintiffs were not entitled to relief from the court.

That didn’t surprise state senator and education committee chairman Dick Brewbaker. The former teacher is planning to resign his chairmanship because of what he calls “colossal failures in education” in Alabama. Even so, he doesn’t think the state will – or should – change from enrollment-based funding to need-based funding. He says districts like Sumter need to step up.

“If you look at the poorest school systems in the state, their local tax effort is extremely low. I mean extremely low,” he says. “And at the same time, they want to make these loud arguments for equity funding. That dog is not going to hunt in Alabama. The students are the innocent victims. But they’re not solely victims of the state legislature.”

Sumter Central High senior Jewel Townsend says it’s unfair but doesn’t see herself as a victim. Instead, she hopes to change the system from the inside. Townsend plans to go to college in the fall — to become a teacher.

This story is part of the NPR reporting project “School Money,” a nationwide collaboration between NPR’s Ed Team and 20 member station reporters exploring how states pay for their public schools and why many are failing to meet the needs of their most vulnerable students. An interactive map where you can see school spending for your district is below.

House Dem. Leader Jeffries responds to air strikes on Iran by U.S. and Israel

NPR's Emily Kwong speaks to House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), who is still calling for a vote on a war powers resolution following a wave of U.S.- and Israel-led airstrikes on Iran.

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed in Israeli strike, ending 36-year iron rule

Khamenei, the Islamic Republic's second supreme leader, has been killed. He had held power since 1989, guiding Iran through difficult times — and overseeing the violent suppression of dissent.

Found: The 19th century silent film that first captured a robot attack

A newly rediscovered 1897 short by famed French filmmaker Georges Méliès is being hailed as the first-ever depiction of a robot in cinema.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.