A New Orleans restaurant owner’s Facebook was hacked. It put her business in jeopardy

Hillary Hanning stands behind the bar of The Little House, the Algiers Point neighborhood restaurant she owns and operates in New Orleans, on January 20, 2025.

“Swamp chic” is how Hillary Hanning describes The Little House, the neighborhood bar she owns on New Orleans’ West Bank.

It’s the kind of place where a customer can sip Croatian orange wine while surrounded by hanging chicken feet and taxidermied alligators.

“Everything with this place, like even the colors on the wall, has something to do with family or a good memory or a friend,” Hanning said from behind the bar. “It’s struggling to death but we’re having fun.”

But that effort to keep the bar alive was made much harder after fraudsters took over her social media accounts and stole about $10,000.

While multi-million dollar ransomware attacks and data thefts targeting governments and industry giants grab headlines, small businesses increasingly find themselves in online scammers’ crosshairs — they’re victimized at a rate of almost four times more than large organizations are, according to a recent Verizon report.

The reason is simple: mom-and-pops are much easier targets. They often have to be their own accountants, facilities managers and plumbers on top of being their own cyber security expert — a task where failure can lead to shutting down. Nearly half of the medium and small sized businesses in a Mastercard survey experienced a cyberattack, with nearly 20% of them going bankrupt or closing.

“Small businesses are the perfect target for bad, malicious cyber actors because they generally have worse security,” Adam McCloskey, the director of the Louisiana Small Business Development Center at Louisiana State University. “Cyber attacks are one of the top threats that small businesses face.”

The most common way an online scam gets started is by the fraudster convincing someone to freely give access. Doing that often means making a would-be-victim frantic. In other words, cyber scams are less about tech and more about emotions.

“They have perfected their art,” Curtis Dukes, executive vice president of security best practices at the Center for Internet Security, said. “They know exactly which pressure points to apply to get you to react.”

It’s even easier when the target already has a dozen other concerns on their mind, which is what happened with Hanning.

In November, Hanning was busy putting together a fundraiser for a North Carolina winery devastated by Hurricane Helene. She got a Facebook message that appeared to be from Meta’s support team about fraudulent activity on her account. In a knee-jerk moment, Hanning clicked the link.

Soon after, her phone exploded with people asking about strange products — trucks, golf cars, televisions and more. Friends called saying those items were listed as for sale on her account. In reality, those posts were from the fraudster using Hanning’s reach to try and scam others.

Hanning could no longer get into the Facebook and Instagram accounts for The Little House with her password — which was no small loss. For companies like Hanning’s, Facebook is not a place for silly memes. It’s mandatory to keep business going. Posting on those accounts, and to neighborhood pages, helped her attract customers for events like crawfish boils.

“We’re so small, we can’t afford discretionary things like advertising,” Hanning said. “We just don’t have the money for it.”

Hanning reached out to Meta and the accounts were eventually shut down. She lost the 4,000 followers she worked hard to build across the two sites and left Hanning shocked she couldn’t get the help she needed from the social media giant. While Meta has online help centers, Hanning said that didn’t help and she couldn’t find a way to connect with a real person at the company.

Cyber security experts are sympathetic to the scale of Meta’s Sisyphean task to protect literal billions of accounts, but also believe the company should do more. Last year, 41 state attorneys general demanded Meta take immediate action over what they said was a “dramatic and persistent spike in complaints” over account takeovers.

A large part of the reason for concern is the scale of the damage from online scams. For Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, more than $250 million was lost to online crimes in 2024.

About three weeks after her accounts were stolen, a friend said he finally got what Hanning wanted. He connected with Hanning on a three-way call and said the other person with them was a Meta representative he found through Facebook’s help center.

Hanning spent four and a half hours on the phone while driving around running errands for both a business owner and mother of three. She described the experience as the best customer service she’s ever had. But when it was over, she realized this was another scam.

This time, she was defrauded for $10,000 — all drained from her mother’s bank account.

“You’re vulnerable and you’re hopeful because you’re like, ‘I’m going to get all this stuff back,’” Hanning said. “And then you’re just humiliated.”

All of Hanning’s problems — believing the first message was from Facebook, the company not restoring her account because she no longer had the latest credentials and the fake customer service — stem from the challenge of proving who people say they are online.

“That challenge of authentication in cyber space is a really big one,” Michael Daniels, head of the Cyber Threat Alliance, said. “And is the root of a lot of the problems that we have in cyber security.”

Daniels said there needs to be a better way for companies to confirm who you are, and vice versa, but admits there is no easy fix. There’s value to internet privacy, but that anonymity provides a smokescreen for bad actors.

Hanning has slowly rebuilt her Instagram following on a new account, now up to a little over a thousand followers. Ultimately, she feels disappointed in herself putting people she loves at risk and for falling for it.

Daniel said he tries to avoid using the “falling for it” language. While it’s important for small business owners to protect themselves in the same way they should lock their doors when closing, the scale of the problem is so large and lopsided against mom-and-pops that it’s unfair to put the blame on them.

“I don’t think someone should beat themselves up for that because the entire deck is stacked against you,” Daniel said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

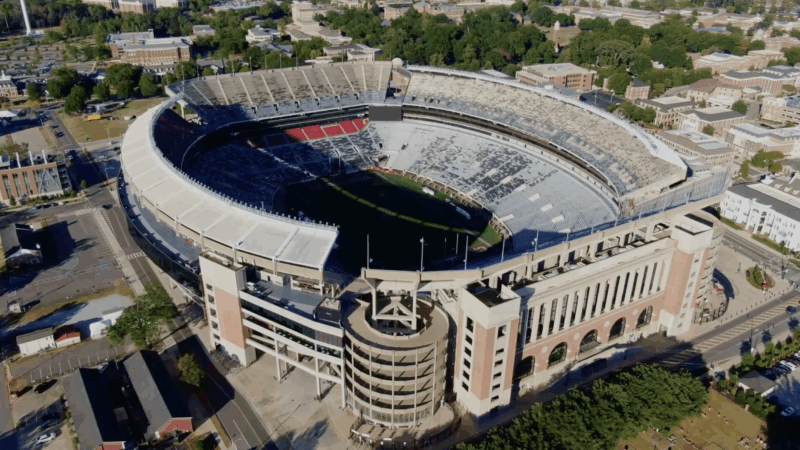

Auburn tabs USF’s Alex Golesh as its next coach, replacing Hugh Freeze on the Plains

The 41-year-old Golesh, who was born in Russia and moved to the United State at age 7, is signing a six-year contract that averages more than $7 million annually to replace Hugh Freeze. Freeze was fired in early November after failing to fix Auburn’s offensive issues in three seasons on the Plains.

Alabama Power seeks to delay rate hike for new gas plant amid outcry

The state’s largest utility has proposed delaying the rate increase from its purchase of a $622 million natural gas plant until 2028.

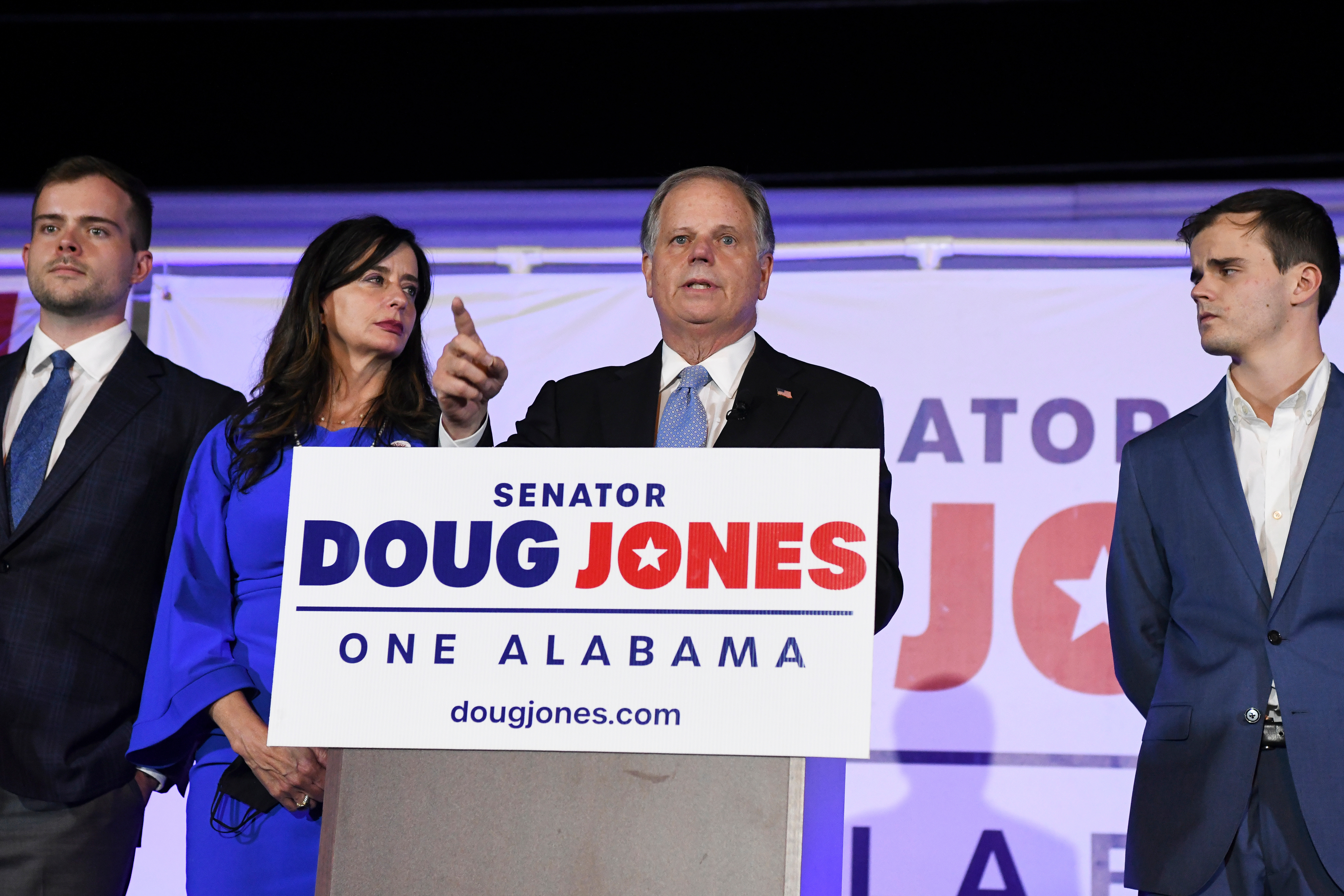

Former U.S. Sen. Doug Jones announces run for Alabama governor

Jones announced his campaign Monday afternoon, hours after filing campaign paperwork with the Secretary of State's Office. His gubernatorial bid could set up a rematch with U.S. Sen. Tommy Tuberville, the Republican who defeated Jones in 2020 and is now running for governor.

Scorching Saturdays: The rising heat threat inside football stadiums

Excessive heat and more frequent medical incidents in Southern college football stadiums could be a warning sign for universities across the country.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring an Audio Editor

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring an Audio Editor to join our award-winning team covering important regional stories across Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana.

Judge orders new Alabama Senate map after ruling found racial gerrymandering

U.S. District Judge Anna Manasco, appointed by President Donald Trump during his first term, issued the ruling Monday putting a new court-selected map in place for the 2026 and 2030 elections.