Doctors remove pig kidney from an Alabama woman after a record 130 days

Towana Looney, a pig kidney transplant recipient, gets a morning check-up with Dr. Jeffrey Stern at NYU Langone Health in New York, Friday, Jan. 24, 2025.

By Lauran Neergaard

WASHINGTON (AP) — An Alabama woman who lived with a pig kidney for a record 130 days had the organ removed after her body began rejecting it and is back on dialysis, doctors announced Friday – a disappointment in the ongoing quest for animal-to-human transplants.

Towana Looney is recovering well from the April 4 removal surgery at NYU Langone Health and has returned home to Gadsden, Alabama. In a statement, she thanked her doctors for “the opportunity to be part of this incredible research.”

“Though the outcome is not what anyone wanted, I know a lot was learned from my 130 days with a pig kidney – and that this can help and inspire many others in their journey to overcoming kidney disease,” Looney added.

Scientists are genetically altering pigs so their organs are more humanlike to address a severe shortage of transplantable human organs. More than 100,000 people are on the U.S. transplant list, most who need a kidney, and thousands die waiting.

Before Looney’s transplant only four other Americans had received experimental xenotransplants of gene-edited pig organs – two hearts and two kidneys that lasted no longer than two months. Those recipients, who were severely ill before the surgery, died.

Now researchers are attempting these transplants in slightly less sick patients, like Looney. A New Hampshire man who received a pig kidney in January is faring well and a rigorous study of pig kidney transplants is set to begin this summer. Chinese researchers also recently announced a successful kidney xenotransplant.

Looney had been on dialysis since 2016 and didn’t qualify for a regular transplant – her body was abnormally primed to reject a human kidney. So she sought out a pig kidney and it functioned well – she called herself “superwoman” and lived longer than anyone with a gene-edited pig organ before, from her Nov. 25 transplant until early April when her body began rejecting it.

NYU xenotransplant pioneer Dr. Robert Montgomery, Looney’s surgeon, said what triggered that rejection is being investigated. But he said Looney and her doctors agreed it would be less risky to remove the pig kidney than to try saving it with higher, riskier doses of anti-rejection drugs.

“We did the safe thing,” Montgomery told The Associated Press. “She’s no worse off than she was before (the xenotransplant) and she would tell you she’s better off because she had this 4½ month break from dialysis.”

Shortly before the rejection began, Looney had suffered an infection related to her prior time on dialysis and her immune-suppressing anti-rejection drugs were slightly lowered, Montgomery said. At the same time, her immune system was reactivating after the transplant. Those factors may have combined to damage the new kidney, he said.

Rejection is a common threat after transplants of human organs, too, and sometimes cost patients their new organ. Doctors face a balancing act in tamping down patients’ immune systems just enough to preserve the new organ while allowing them to fight infection.

It’s an even bigger challenge with xenotransplantation. While these pig organs have been altered to help prevent immediate rejection, patients still require immune-suppressing drugs. Which drugs are best to prevent different, later forms of rejection isn’t clear, said Dr. Tatsuo Kawai of Massachusetts General Hospital, another xenotransplant pioneer. Different research groups are using different combinations, he said.

“When we have more experience, we’ll know what kind of immunosuppression is really necessary for xenotransplant,” Kawai said

Montgomery said Looney’s experience offers valuable lessons for the upcoming clinical trial.

Making xenotransplant ultimately work “is going to be won with singles and doubles, not swinging for the fence every time we do one of these,” he said.

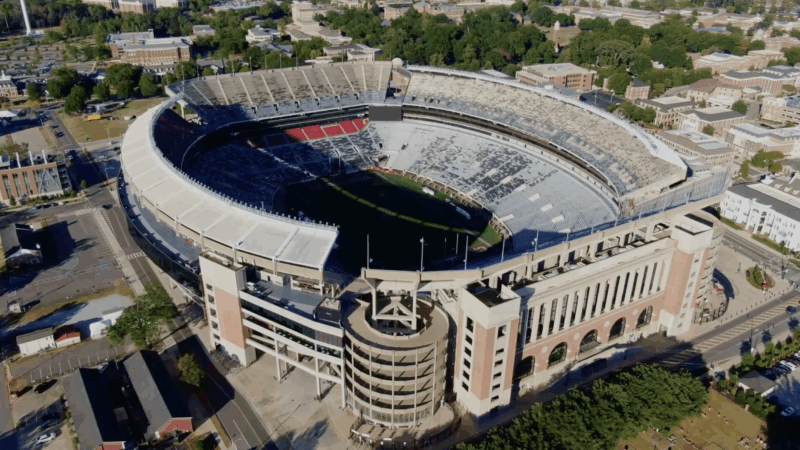

Auburn tabs USF’s Alex Golesh as its next coach, replacing Hugh Freeze on the Plains

The 41-year-old Golesh, who was born in Russia and moved to the United State at age 7, is signing a six-year contract that averages more than $7 million annually to replace Hugh Freeze. Freeze was fired in early November after failing to fix Auburn’s offensive issues in three seasons on the Plains.

Alabama Power seeks to delay rate hike for new gas plant amid outcry

The state’s largest utility has proposed delaying the rate increase from its purchase of a $622 million natural gas plant until 2028.

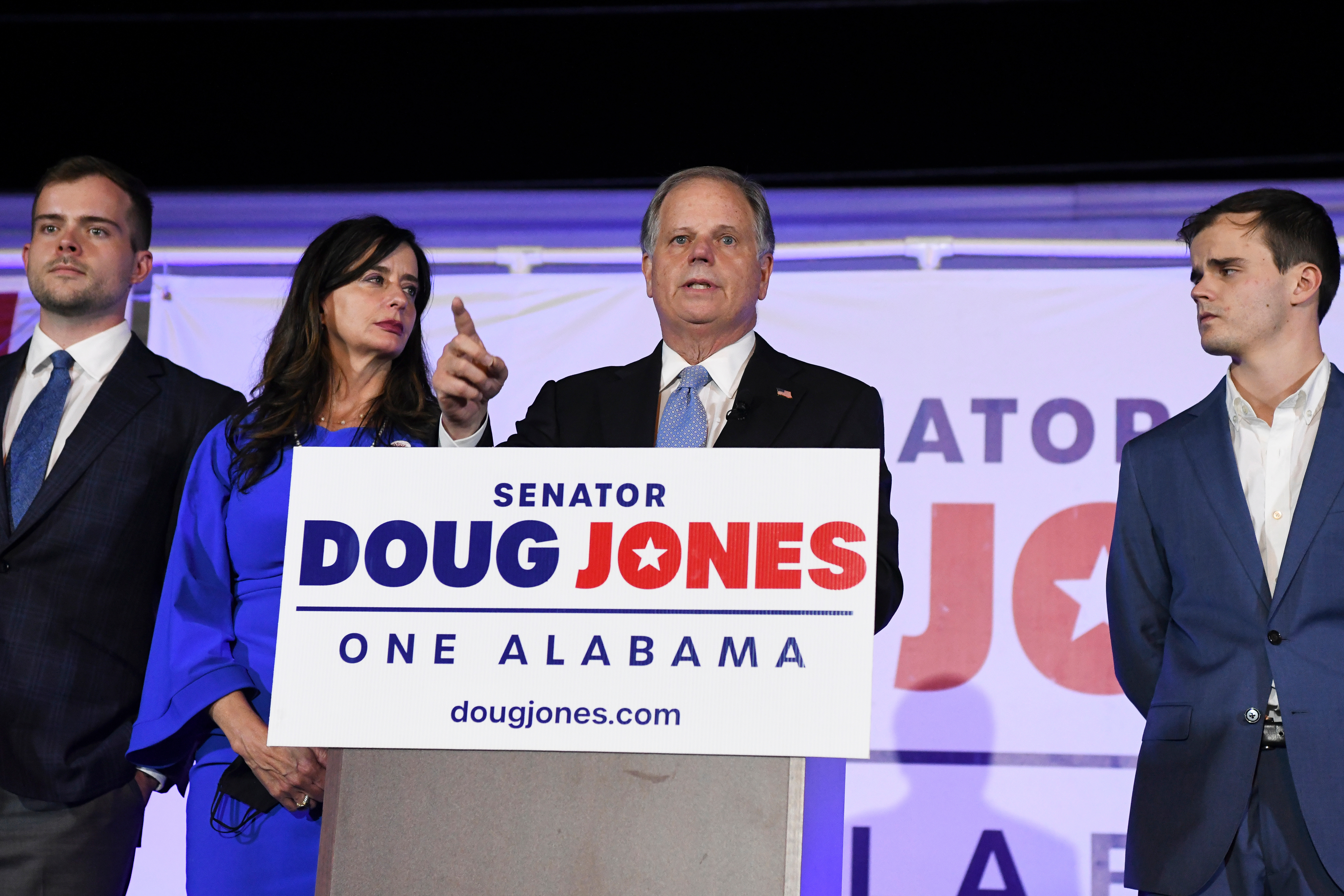

Former U.S. Sen. Doug Jones announces run for Alabama governor

Jones announced his campaign Monday afternoon, hours after filing campaign paperwork with the Secretary of State's Office. His gubernatorial bid could set up a rematch with U.S. Sen. Tommy Tuberville, the Republican who defeated Jones in 2020 and is now running for governor.

Scorching Saturdays: The rising heat threat inside football stadiums

Excessive heat and more frequent medical incidents in Southern college football stadiums could be a warning sign for universities across the country.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring an Audio Editor

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring an Audio Editor to join our award-winning team covering important regional stories across Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana.

Judge orders new Alabama Senate map after ruling found racial gerrymandering

U.S. District Judge Anna Manasco, appointed by President Donald Trump during his first term, issued the ruling Monday putting a new court-selected map in place for the 2026 and 2030 elections.