Looking into Alabama’s ‘Blood Money’: how taxpayers foot the bill for lawsuits by prisoners

The Alabama Department of Corrections settled more than 100 lawsuits against its corrections officers for excessive use of force since 2020. Inmates say officers left them with broken bones and brain damage. Beth Shelburne, a Birmingham-based independent investigative reporter, found that taxpayers are covering the cost in her four-part series for the Alabama Reflector called “Blood Money.” WBHM’s Noelle Annonen spoke with Shelburne.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity.

Let’s start with Koty Williams. You cover a lot of cases in your series, but you spend an entire article focusing on one man and one case. What sets him apart?

Koty Williams was a young man who was serving a short prison sentence in Alabama for convictions related to opioid addiction. He was called out of a dorm during a shakedown by a group of officers. They accused him of hiding some contraband items. Koty Williams denied that they were his. He still maintains that. But these officers, according to him, took him into the prison’s barbershop and beat him to the point that his hip was broken.

But the prison never confirmed that he sustained this injury, nor did they seem interested in finding out if it was true. Koty Williams recovered from his injury, but when he was released from the Department of Corrections, he sued, alleging excessive force. That goes through about two years of litigation and then the state offers a $140,000 settlement to him, which he accepts. Koty Williams is out of prison now and he told me that this really felt like the only measure of accountability that he could get from the system because everyone that he told about the incident didn’t believe him or didn’t investigate it. They just blew it off.

Officers to this day have denied that this incident happened. That’s what’s so perplexing about these cases: the state will continue to deny the claims on their face but will quietly negotiate these paid settlements behind closed doors, usually sealed in court records.

I’ve examined many of the personnel files connected to these officers and there’s nothing in their personnel file to reflect the allegations from these lawsuits. So while this is a story about an abusive system, I think it’s also a story that illustrates dysfunctional government at its worst.

What do government officials have to say about this?

I submitted multiple requests for comment, phone calls, emails, even a submitted list of questions to our attorney general’s office and it was never acknowledged. Attorney General Steve Marshall is responsible for handling all litigation involving the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC). ADOC responded to my questions in writing, but they were pretty standard, boilerplate answers. The governor has just been radio silent on all of this.

The most challenging part in doing this reporting is dealing with this strange wall of silence in spite of something so incredibly serious and life-threatening. Handling this issue takes up so many state resources and dollars in the midst of this crisis where people are dying in our prisons.

You mentioned dollars and resources. In your series, you talk about the accounts that pay for these lawsuits, funded by the taxpayer. Can you give us an idea of how much money is being spent here?

We identified $17 million that have been taken out of funds between 2020 and 2024 to address this litigation. The vast majority of that money, almost $13 million out of the $17 million, went to attorneys. The plaintiffs, on the other hand, really received a pittance. The median settlement in these 94 excessive force cases was just $8,000.

One of the attorneys that I interviewed said a question worth asking is: what does this say about our collective values? We are using a fund that’s set up to defend state employees, yes, when they’re sued. But it is also there to give something to people who are wronged.

These are the kinds of incidents where officers are beating people into comas, sending them to the hospital, knocking out teeth, breaking bones, and causing, in some cases, permanent injury and disfigurement. If that was happening in any other space, it would be completely unacceptable to us in society. So why isn’t it unacceptable when it’s happening to people in prison?

What should our audience take away from your story?

Well, I’m always hoping that people that aren’t directly impacted by mass incarceration will hear about these stories and will start to care. But if they don’t care about people in prison being harmed, I’m hoping that they will care about the way that their taxes are being used and how that money is going to private attorneys who are getting rich off our prison crisis.

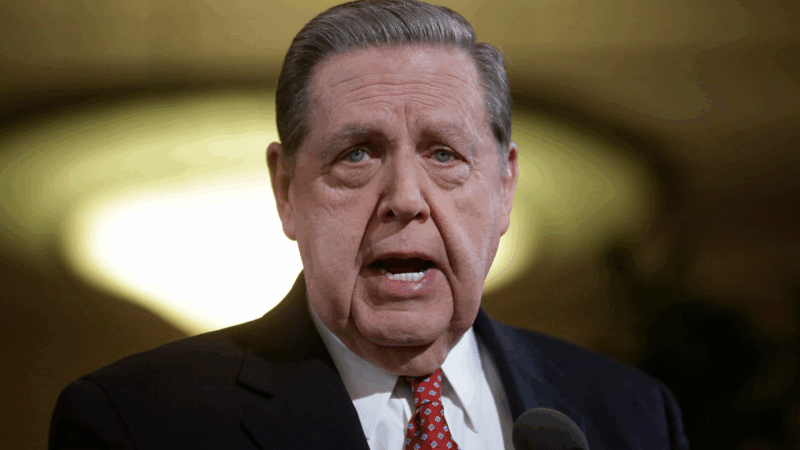

Jeffrey R. Holland, next in line to lead Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, dies at 85

Jeffrey R. Holland led the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, a key governing body. He was next in line to become the church's president.

Winter storm brings heavy snow and ice to busy holiday travel weekend

A powerful winter storm is impacting parts of the U.S. with major snowfall, ice, and below zero wind chills. The conditions are disrupting holiday travel and could last through next week.

Disability rights advocate Bob Kafka dead at 79

Bob Kafka was an organizer with ADAPT (American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today), a group which advocates for policy change to support people with disabilities.

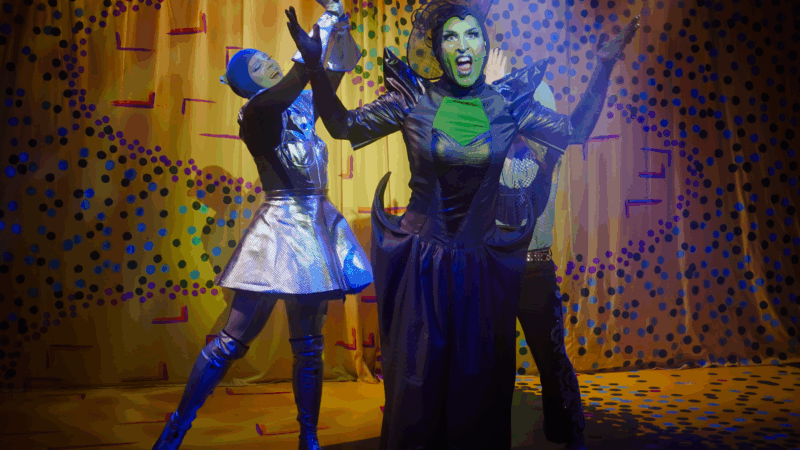

‘It’s behind you!’ How Britain goes wild for pantomimes during the holidays

Pantomimes are plays based on a well-known story — often a fairy tale — which are given a bawdy twist. The audience is expected to join in throughout, shouting as loudly as they can.

Kennedy Center vows to sue musician who canceled performance over Trump name change

The Kennedy Center is planning legal action after jazz musician Chuck Redd canceled an annual holiday concert. Redd pulled out after President Trump's name appeared on the building.

Our top global photo stories from 2025: Fearless women, solo polar bear, healing soups

These stunning photos include a polar bear in a Chinese zoo, a teen in Zambia facing an uncertain future, Mongolian kids watching TV in a tent, a chef prepping a bowl of good-for-you soup.