The story of Lilly Ledbetter’s fight for equal pay comes to the big screen

Lilly Ledbetter is an icon in the fight for equal pay. Ledbetter was a manager at the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. plant in Gadsden. Once she learned she was earning less than her male colleagues – she sued the plant. Ledbetter’s story is being turned into a movie, which comes out Friday.

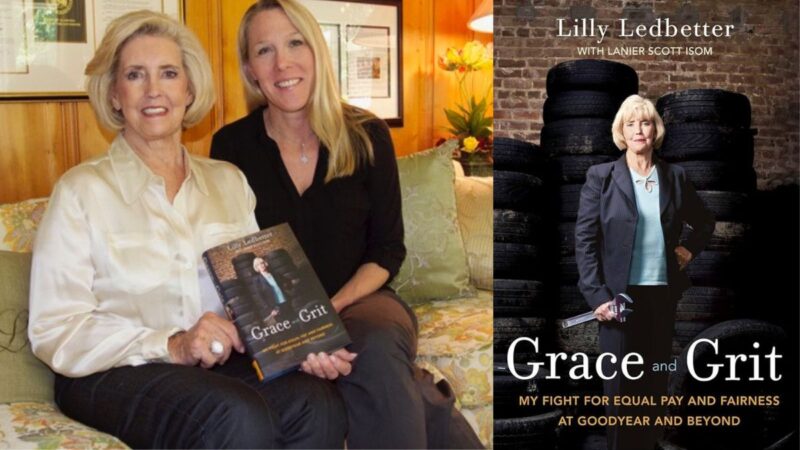

Lanier Isom is a reporter from Birmingham who has covered Ledbetter extensively. Isom took the unofficial role as Ledbetter’s historian on the movie’s set. She sat down with WBHM’s Kelsey Shelton to explain why Ledbetter’s story needs to be told today.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Lanier, if you could please just tell us about Lilly’s story – introduce us to Lilly.

Lilly Ledbetter grew up in Possum Trot, Alabama, which is in North Alabama, a tiny town, and she grew up without any running water or electricity. She grew up picking cotton to earn extra money. At one point her clothes were sewn out of feed sacks, so she grew up in abject poverty and only had a high school education. But she was full of determination for a better life, and ambition.

And how did Lilly find her way at the Goodyear in Gadsden?

In 1979, she saw an ad in Businessweek for the new radial plant. And at the time she was working at H&R Block and she was like the manager over a huge area. She was really good with numbers and math. She saw the ad and they were hiring women and Backs in management for the very first time. This is 1979 in North Alabama. The Goodyear Plant, which is the way out for a better life for the majority of people in the community, the Goodyear plant always signified in Lilly’s growing up the families that got to go to the beach over spring break, that had the nice clothes. So she knew that there would be a good paycheck in management and her kids were about college age at that time. So, she wanted to do the right thing for her family. She always put her family first.

What was Lilly going through at the Goodyear?

You can’t even imagine the level and consistency of harassment that she experienced. It went from her supervisor telling her that she’d get a promotion if she went to the Ramada Inn with him, to her brakes being cut, to her windshield being also cut out, to tobacco juice all over her car, to being followed home at night. It was constant. So she faced real physical harm and danger from the men who did not want her there.

And then all that on top of being paid less than them.

Exactly. So she sues in 1999, and John Goldfarb is her attorney, and she wins in the Northern District Court over $3 million, but of course that’s reduced to $360,000, I think. Goodyear appeals, the circuit court rules against her saying she should have sued within 180 days of working at Goodyear when she started. And then she takes it all the way to the Supreme Court. And that’s when Ruth Bader Ginsburg stood up in her dissent and said, ‘Lilly, you have to change the law back to its original intent.’ And in 2009, President Obama signed into law the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Restoration Act.

You wrote one of the goals of reporting on Lilly was to answer the question, ‘Why Lilly?’ So what is it about her life and journey that you think makes her story one that needs to be told?

I think it needs to be told now more than ever because of the times we live in and the rollback of women’s rights and workers’ rights in the workplace. Lilly never ever gave up. Most women are underpaid. In fact, the pay gap is greater than it’s ever been in the past 20 years. Why Lilly, who has the law named after her, when the majority of us have been underpaid in the workplace. But Lilly just had this determination and she refused to accept defeat, so to speak. She had a lot of losses and she never saw a penny of anything. What she did was for the good of American families. And she used to always say, this is not a women’s issue. This is a family issue; this is important from Walmart to Wall Street. Lilly just had the grit.

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.

Iran fires missiles at Israel and Gulf states after U.S.-Israeli strike kills Khamenei

Iran fired missiles at targets in Israel and Gulf Arab states Sunday after vowing massive retaliation for the killing of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei by the United States and Israel.

House Dem. Leader Jeffries responds to air strikes on Iran by U.S. and Israel

NPR's Emily Kwong speaks to House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), who is still calling for a vote on a war powers resolution following a wave of U.S.- and Israel-led airstrikes on Iran.

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed in Israeli strike, ending 36-year iron rule

Khamenei, the Islamic Republic's second supreme leader, has been killed. He had held power since 1989, guiding Iran through difficult times — and overseeing the violent suppression of dissent.

Found: The 19th century silent film that first captured a robot attack

A newly rediscovered 1897 short by famed French filmmaker Georges Méliès is being hailed as the first-ever depiction of a robot in cinema.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."