Katrina changed how jails deal with natural disasters. 20 years later, challenges remain

Hannibal Nicholls poses for a portrait on Sept. 3, 2025. He was locked in an Orleans Parish Prison facility as Hurricane Katrina struck in August 2005.

Twenty years later, Hannibal Nicholls recounts what was going on in his life toward the end of August 2005.

He was in college and was engaged to his fiancée. Then suddenly, he was in the Orleans Parish Prison complex, fearing for his life as floodwater began creeping into one of its buildings.

“We’re literally looking at how much time we have left before we suffocate, drown and die because the water’s coming up, and no one’s getting us out,” he said.

As a mandatory evacuation was called in New Orleans, Nicholls was among thousands of people who remained in the parish’s jail facilities back then, many of whom told advocates they endured desperate days without food or power.

The event adds to a dark catalog of crises during Hurricane Katrina and the levee failures. Two decades later, corrections officials and sheriffs describe a changed landscape from that time, with lessons learned as they face the complex task of hurricane planning for incarcerated people.

As climate-related weather events intensify, advocates warn that natural disasters pose even more of a threat to people in lockups. Experts who have studied jails and prisons and disasters say improvements could be made to shore up the field’s management of these emergencies, which sometimes show a hodgepodge of plans.

“Especially at the county level with county jails, there’s no standard response or preparedness,” said Carl Dement, an assistant professor with the University of Central Oklahoma who has studied carceral evacuations, including on the Gulf Coast.

“It’s pretty much spread out — almost as many different plans as there are jails.”

At least 6,000 people were thought to have been in the Orleans jail complex during Katrina, including women and children, according to a more than 140-page ACLU National Prison Project report published with partner groups in 2006.

That report drew on information received from more than 1,300 evacuees, including interviews with incarcerated people, deputies and family members. It found the Orleans facility had little planning in place for people in custody during a storm, said David Fathi, now the director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project.

“When the hurricane did strike, these mostly Black and brown and impoverished people were simply treated as expendable,” Fathi — who was not deeply involved with the report, but was with the National Prison Project at the time — said.

The administration at the time denied many accounts of conditions inside the jail after the storm made landfall, including dismissing them as “fiction,” according to contemporaneous news articles, including those cited by the report.

Those locked up included Nancy Mayer’s son, Raphael Schwarz, who was arrested during the evening of Midsummer Mardi Gras for public drunkenness a couple of days before Katrina. As the storm made landfall, she said he woke up in a jail dayroom, the water rising.

“The water was like, five inches. He said he had taken off his shoes and slacks, and they were floating away,” Mayer said of her son, who died a couple of years ago. (Schwarz spoke to her about his experiences, she read his journals and he also spoke to the ACLU.)

Schwarz was crammed into a small cell with several other people, and he thought he’d been left to die, according to his mother and his writings.

“I really and truly know what it is like to be stuffed in a box with my own kind and left to rot. The prisoners of Katrina were left sleeping head to foot in a tin can of sewage and filth without air, food or water,” Mayer read aloud from Schwarz’s journal.

Major Silas Phipps Jr. with the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office said the legacy of what happened during Katrina goes beyond the agency.

“I don’t think there’s anyone in the city that thought we would not survive Katrina and then have to deal with the entire city flooding,” he said in an interview before the start of this year’s hurricane season. “So Katrina has taught us to plan for the worst possible scenario and work back from there.”

He acknowledged that rapid intensification of storms will create new headaches, both for the sheriff’s office and the state — but that’s matched by improved forecasting from the National Weather Service.

Some advocates have criticized the response following more recent Louisiana storms.

Colin Reingold, formerly of The Promise of Justice Initiative, said that group fielded calls from people who couldn’t find their jailed loved ones or reported problems with heat and power after Hurricane Ida. (The state Department of Public Safety & Corrections disputed some reports of issues at the time.)

“It’s always going to be a challenge in a state that’s so addicted to incarceration, and where every facility is almost always full,” he said.

‘A little bit more preparation’

Sheriffs and corrections officials described changes since Hurricane Katrina, including better communication tools and refined hurricane predictions.

That’s as they consider the numerous hurdles embedded in their task: making the call to stay or go, safely transporting incarcerated people, records management and more.

Back during Katrina, Seth Smith — chief of operations in the DPS&C Division of Prison Operations — worked at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola. He said prison staff had little information about many of the evacuees who arrived there.

“They may have just had the clothes on their back, and the clothes on their back may have been wet,” Smith said.

Today, he believes there “is a little bit more preparation on the front end than what historically was done.” That looks like evacuation plans submitted from parish jails to the state DPS&C, including average jail populations, demographics and other factors. Facilities below Interstate Highway 10 are encouraged to partner with another site above it.

In Orleans Parish, Phipps and Sheriff Susan Hutson said their hurricane planning today includes annual hurricane meetings, evacuation drills and debriefing after events. (Neither was with the agency during Katrina, and Hutson will leave office next year.)

The new jail complex in Orleans Parish, which formally opened in 2015, was built to physically withstand a category 4 hurricane, Hutson said. But the office likely wouldn’t take that chance, considering potential concerns about city infrastructure, water and power.

Still, the jail tries to restock three weeks of supplies, like food and medications, in May.

“We cannot predict what God is gonna do, but we try to stay as informed as possible. And we’ve already made the call,” Hutson said. “[Category] 2 and above, we’re ready to go.”

Down in Lafourche Parish, Sheriff Craig Webre said New Orleans potentially had a “false sense of security” before Katrina. He described thinking informed by that time when building his parish’s own new jail, also built for a category 4 storm.

“The Katrina experience led us to make sure that we built a facility to withstand the elements and the challenges that are presented to us in South Louisiana, particularly hurricanes,” he said.

That meant Webre chose not to evacuate during Hurricane Ida, which made landfall in Lafourche Parish. He said generators held up and still thinks it was the right decision.

“For the foreseeable future, anything [category] 4 or less, we have no reason to evacuate,” he said.

Burl Cain, the former Angola warden who now heads Mississippi’s prison system, helped coordinate the evacuation of the Orleans jail complex, which was a “rough time,” he said. He said a lesson was to evacuate coastal jails as storms approach.

“Nobody wants to go through another Katrina. You cannot allow the inmates to get caught in the storm, ‘cause you got to take care of them,” he said.

“We gambled in New Orleans, and we lost.”

‘A ship that’s sinking’

Nicholls had been arrested a few days before the storm on a misdemeanor charge, which he claimed was based on false allegations. He expected to get out right away, and at first had no inkling that a storm was approaching.

Eventually, the reality of the situation sank in, as well as what he calls a state of shock.

“Power’s gonna go out. No telling how long this is gonna be. No telling how high the water’s gonna be,” he recalled, describing storing cups of water in his jail cell with a plan to ration them if needed.

When the storm hit, he said water began seeping into the cells around him in the Templeman III building, like being “in the bottom of a ship that’s sinking and no way to get out,” he said.

He was eventually brought to an upstairs gymnasium with about a hundred people, which was sweltering with heat.

“And the deputy ended up just looking at us and [we’re] like, ‘Hey man, what are we gonna do? How we doing this?’ And he literally looked at us, and put up the peace sign and left,” he said.

As days passed, he said hunger set in, and some began to have health complications. Men began beating a hole in the wall using makeshift tools: a hand truck and a torn-down basketball goal.

He said they punched a hole in the wall large enough for a human body to pass through. People began dropping through to the floodwaters below.

“And as we hit the water, here are the deputies. As soon as you hit the water, ‘Come up, put your hands up,'” Nicholls said.

Nicholls eventually reached the Broad Street overpass bridge, in a scene that has now become grimly iconic — “that classic scene or video of all the people in orange,” he said.

Eventually, “my body just went numb. Dehydration, no food, no nothing, no water, the heat,” he said.

‘Risks’ continue

Experts and advocates say that decades later, natural disasters still threaten incarcerated people, and that disaster planning could be improved for carceral settings.

Fathi pointed to wildfires on the West Coast and an instance in South Carolina of incarcerated people not being included in evacuations as instances that have lately threatened the lives of people in lockups.

But even as “the risks of potentially catastrophic loss of life from extreme climate events continue to increase, we don’t see prison officials really keeping up” with their duty to prepare and protect people in custody, he said.

He believes officials should bring the same spirit of “detail and focus” when planning for natural disasters that they have for things like riots and other security instances.

Accounts more recent than Katrina help shed further light on what can go wrong, as in one recent study that spoke with people in Texas about being incarcerated during climate disasters, such as heat waves and hurricanes, including Hurricane Harvey.

“These disasters were forcing people into really small cells that weren’t meant for the amount of people they were forced to hold, without power or potable water,” Katherine LeMasters, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado and the study’s lead author, said.

LeMasters stressed the need for better planning for carceral contexts overall. There is no federal emergency planning for prisons and jails, she said, leaving it up to state and local governments. State plans for climate disasters can be lacking, too.

She said those plans are crucial and should be made public, adding that incarcerated people are deprived of the agency to make these decisions on their own.

“If the recommendation is for the community to leave, then the recommendation should also be for incarcerated individuals to leave,” she said.

Dement said in his research, it was sometimes difficult to get information from carceral administrators about their plans.

Possible recommendations for improvements in this field, he said, include administrators working more closely with emergency management offices and refining systems that can help track people who are evacuating. A “hurricane packet” of information can help set expectations for staff.

Overall, “it’s about treating human beings the way humans deserve to be treated,” he said.

‘Heat will rise’

After being evacuated, Nicholls described spending weeks being shuffled from facility to facility, and it would be some time before he was able to communicate with his family or fiancée.

“And when I finally reached her, she was just in tears, crying, that she had heard from me. And I was as well,” he said.

He said he was released in October wearing a reminder of what he’d been through — an orange inmate’s jumpsuit. The charge he was originally arrested for was dropped.

It took a long time, he said, before he could start to process what had happened to him. He feels that jails today should have evacuation plans in place.

“These buildings should not be kept with people in them. Generators will go out. Power will go out. Heat will rise. And when that happens, the body can only go for so long,” he said.

Mayer, Schwarz’s mom, said he was evacuated to Elayn Hunt Correctional Center before ultimately being released. She said his head was shaved, and he was very thin.

“I said, ‘Did you try to get any food when you were there?’ And he said, ‘Are you kidding? I wouldn’t want to be killed for a stale peanut butter and jelly sandwich,'” Mayer recounted.

She, too, encouraged hurricane planning, starting with limiting arrests that lead to jail and including plans for if communication breaks down.

“They knew there were still people there, and they left them there,” she said.

After he was released, Schwarz went back to St. Louis, where he had lived before moving to New Orleans. Despite what he’d been through, he maintained his close ties to New Orleans, to the point where friends in St. Louis celebrated him with a second line after he died.

Mayer thinks the experiences during Katrina affected his life. She believes he had a form of post-traumatic stress, though he was never diagnosed. He was bothered by interactions with police, and he was always afraid during storms.

But she said he didn’t want people to forget what had happened during Katrina. She had nightmares after reading his journals about what transpired.

“I would wake up at night. My heart was beating and there were tears on my face,” she said. “I can’t believe that happened to my son.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

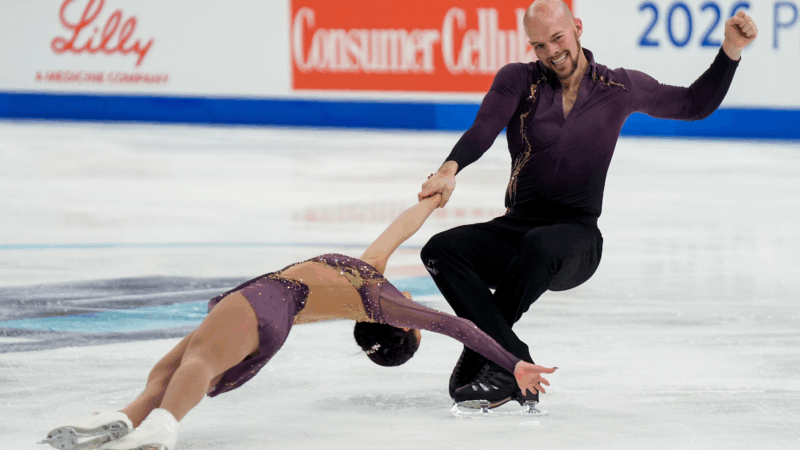

America’s top figure skaters dazzled St. Louis. I left with a new love for the sport.

The U.S. Figure Skating National Championships brought the who's who of the sport to St. Louis. St. Louis Public Radio Visuals Editor Brian Munoz left a new fan of the Olympic sport.

DHS restricts congressional visits to ICE facilities in Minneapolis with new policy

A memo from Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, obtained by NPR, instructs her staff that visits should be requested at least seven days in advance.

Historic upset in English soccer’s FA Cup as Macclesfield beat holders Crystal Palace

The result marks the first time in 117 years that a side from outside the major national leagues has eliminated the reigning FA Cup holders.

Venezuela’s exiles in Chile caught between hope and uncertainty

Initial joy among Venezuela's diaspora in Chile has given way to caution, as questions grow over what Maduro's capture means for the country — and for those who fled it.

Sunday Puzzle: Pet theory

NPR's Sacha Pfeiffer plays the puzzle with KAMW listener Daniel Abramson of Albuquerque, N.M, and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

Inside a Gaza medical clinic at risk of shutting down after an Israeli ban

A recent Israeli decision to bar Doctors Without Borders and other aid groups means international staff and aid can no longer enter Gaza or the West Bank. Local staff must rely on dwindling supplies and no international expertise.