Deep cuts to NIH funding would cause economic harm across Trump-friendly Alabama

A banner hangs in downtown Birmingham, Alabama, boasting of the University of Alabama’s status as one of the top recipients of National Institutes of Health funding.

A federal judge on Monday temporarily blocked a Trump Administration policy that would have made deep cuts to health research funding at universities, medical schools, hospitals and other scientific institutions.

But the decision has done little to quell worries about what a potential loss of grant dollars would mean for the cities and states that rely on National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding, including in deep red states like Alabama.

Birmingham, Alabama has become one of the country’s leading hubs for biomedical research. Banners downtown brag about the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s (UAB) status in the top 1% of institutions for NIH funding, bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars into the region.

Economists and politicians in the state are quick to clarify a few points: UAB is not only the largest employer for Birmingham, but all of Alabama. UAB is an essential piece of the state’s economy. And NIH funding is foundational to UAB.

In an emailed statement, the university warned that if the funding cuts went through, “virtually all areas of research would slow.”

This pits two of President Donald Trump’s campaign promises against each other — to clear out government waste and improve the economy. In this case, the budget slashing would send harmful ripples across a state that’s consistently voted for Trump.

Life saving research at risk

UAB received at least $334 million last year from the NIH, according to the agency’s website. That cash fuels research into the country’s leading causes of death, including Azheimer’s, stroke and heart disease, according to an emailed statement from the UAB about the cuts.

“What’s happened over the years with billions of dollars in research has literally saved lives,” Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin said. “This has a real effect downstream on everyday Alabamians.”

The actual cuts proposed by the Trump Administration would be to indirect funding — a portion of grants dedicated to covering administrative costs like facilities and lab managers. In the memo announcing the cuts, the NIH said it was paying a much higher rate than private grantees. For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation caps indirect costs at 10% of the direct costs like research personnel and supplies. NIH has typically given around 28%.

The memo took time to actually credit UAB as the rare university that demands private grantees accept the same rates as it charges the NIH. UAB said its average indirect rate across NIH grants is 33%.

While economists say there’s a case for lowering indirect rates, the suddenness of these cuts and applying them to existing grants researchers are currently using to fuel their research is what’s causing so much disruption. Whether the funding is labeled under direct or indirect costs, it would still mean tens of millions stripped away from UAB and similar universities to support medical research.

Alabama Sen. Katie Britt, a Republican, said in an emailed statement that she’s all for cutting administrative bloat, but wants to work with the Trump Administration to do it in a way that doesn’t hinder important research.

She also said these cuts should not cause the U.S. to lose its competitive edge on other countries, like China.

Birmingham’s economy is built around research

The research done at UAB has not just helped save lives, but also helped save Birmingham’s economy.

The city was founded in the 1870s due to the rich mineral deposits around it, needed to make steel. That industry supported the city until it collapsed in the 1970s and 1980s. Around the same time, UAB’s Biomedical Engineering department was formed and eventually grew to the point where the city revolved around UAB and its research.

A large part of that growth comes down to NIH funding.

Sara Helms McCarty, an economist at nearby Samford University, said it’s difficult to know exactly what cuts would do to the city’s and state’s economies, but it would certainly mean a loss of jobs.

McCarty’s friends working in UAB labs said they’re dusting off resumes, unsure what a loss of funding would mean for their position.

Beyond individuals, McCarty said a decline in Birmingham’s biomedical scene would ripple out across the region.

“That is something, if it is disrupted, it will greatly impact what we see in our state and in our city,” McCarty said. “It will affect businesses, restaurants, real estate — all of it.”

UAB holds WBHM’s broadcast license, but our news and business departments operate independently.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

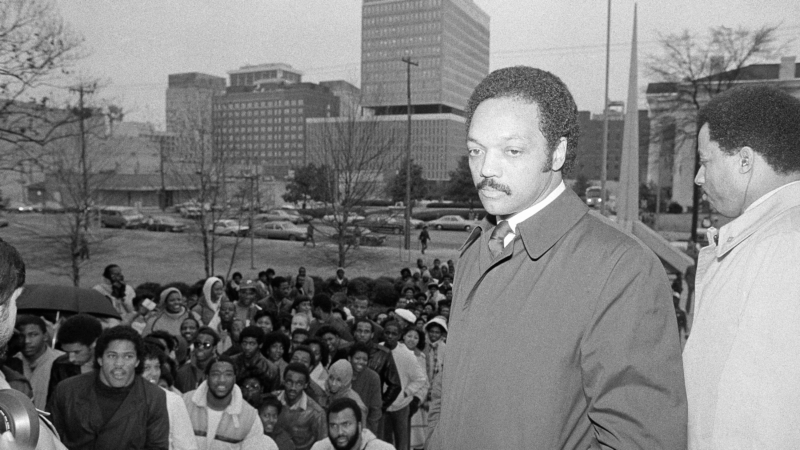

Opinion: The enduring dignity of Jesse Jackson

Rev. Jesse Jackson died this week at age 84. NPR's Scott Simon remembers covering Jackson's 1984 presidential campaign in Mississippi.

From cubicles to kitchens: How empty offices are becoming homes

Many U.S. cities have too many office buildings and not enough homes. Developers are now converting some old offices into apartments and condos, but it's going slowly.

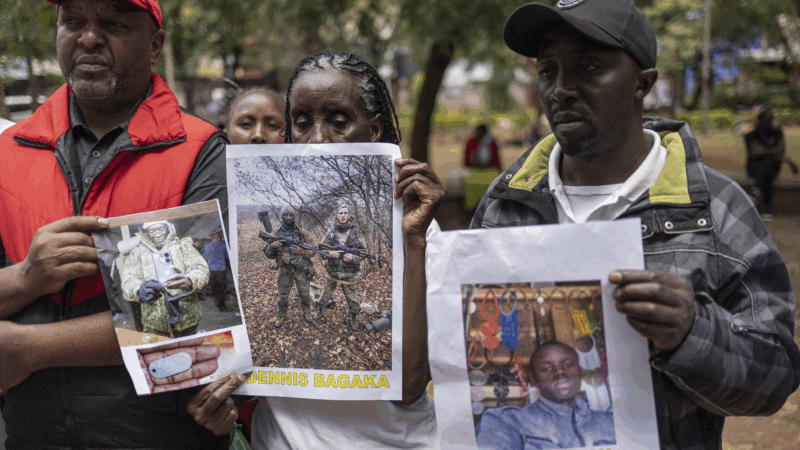

‘Given a gun and sent to die’: Kenyans lured to fight for Russia in Ukraine

Kenya's intelligence service warns that over 1,000 citizens may have been recruited to fight for Russia in Ukraine, many under false pretenses.

With U.S. forces in position, Trump mulls his options for Iran

President Trump says he hasn't decided whether to attack Iran. While he weighs his options, a military buildup over the past month means the U.S. now has an expansive presence in the region.

Stop picking at your cuticles! 7 ways to keep your nails healthy and strong

Should you trim your cuticles? How do you cut a hangnail? Is it better to use a cardboard or crystal file? Dermatologists and a nail technician share basic nail health tips.

Former top general calls military’s removal of trans troops a costly mistake

As several global tensions simmer, the Pentagon is removing thousands of transgender troops under an anti-DEI push. How might a focus on gender identity distract from mission readiness?