Birmingham’s Prince Hall Masonic Temple to be restored as hub of Black-owned businesses

By Noelle Annonen and Jessica Sims, Reflect Alabama Fellow

Llevelyn Rhone, director of Direct Invest Development, stood in the auditorium of the Prince Hall Masonic Temple, a Renaissance-Revival style building at the heart of Birmingham’s civil rights district.

Peeling, pale blue plaster hangs from the ceiling and walls. Dusty floorboards, which once served as a basketball court, creak as a small crowd of tour participants gathered around Rhone.

“Somebody mentioned the blue color that you see,” Rhone said. “This is not a part of the original.”

The hall is one of Birmingham’s most significant, but worn, historic buildings. Plans to restore the eight-story, downtown, former hub of Black-owned businesses are underway.

Rhone stood in front of a stage trimmed with white crown molding, on which sat a single, grand piano. He said the blue paint is not the only thing that has been added to the space since the temple was completed 101 years ago.

“These chandeliers, they were not here,” Rhone said, gesturing to crystalline chandeliers hanging over the large event space. “And the air conditioning vents were not here. But by and large what you’ll see though from an architectural standpoint is what this building looked like, absent the blue, in 1924.”

A balcony overlooks the stage and its 2,000 seat auditorium. The Booker T. Washington Library, the first library opened to Black people in Alabama, once filled the story just below the event hall. There were also Black-owned businesses like cobblers, seamstresses and drug stores. Offices on the upper floors housed dentists and doctors offices as well as offices for organizations like the NAACP. The basement housed a bowling alley and a pool hall.

“The vision was to not only have this be a building for the Masons, but for the larger community,” Rhone said. “A place where you could get those services that you were unwelcome to in other parts of the city at the time.”

He said it was once the largest Black owned building in the country.

“This building not only preserves a significant part of the African American story, but it’s a part of the American story,” Rhone said.

The temple was built for the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the Free and Accepted Masons of Alabama. Their current grand master, Corey Hawkins, describes the hall as somewhere that Black Alabamians could feel safe during the Jim Crow era.

“If they sat in the balcony of the auditorium, it was by choice, not because they had to,” Hawkins said. “African Americans could enter the front door of the building and not the back door.”

The masonic temple even housed one of the first major civil rights events in the city back in 1932.

“It’s time for us to pay back and to serve the temple and give it a restoration that will bring it back to its heyday,” Hawkins said.

Over the last few years, Historic District Developers has been pushing for a restoration of the Prince Hall temple. Developers said the goal is to keep as much of the original structure intact as possible. This would pay respect not only to the building’s 100 year history but to its architect, Robert Robinson Taylor.

“Robert Taylor is America’s first licensed Black architect, and he and his partner would design this beautiful building that has so much authentic historic fabric and integrity,” Brent Leggs, Executive Director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, said.

Taylor was the first Black student who studied at and graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Booker T. Washington later enlisted Taylor to help design much of the Tuskegee University campus. Taylor’s vision, developers said, centered on helping people who often did not have access to good architects, and building something functional that would last. Leggs pointed out that the temple once represented opportunity for Black people in the South.

“It is quite unfortunate that it is derelict and has been vacant for decades,” Leggs said. “It’s unfortunate that a place of this significance, both architecturally and historically, is not currently restored at the highest standards of preservation practice.”

The building cost $658,000 to build in 1922 and was funded entirely by Black Alabamians. It closed in 2011 following an economic downturn and high maintenance costs. Today, Historic District Developers representatives gave an initial estimate that the restoration will cost more than $30 million. They anticipated that it could take another 3 years to complete the project.

Kwesi Daniels, head of the architecture department at Tuskegee University, said developers want to honor the building’s history as they prepare it for its future.

“You cannot do any work without understanding what has happened and who has touched these grounds and what are the narratives and how has this particular space shaped a larger environment,” Daniels said.

Renovating the Prince Hall Masonic Temple is more than just about restoring a building. It’s about preserving Birmingham’s history.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

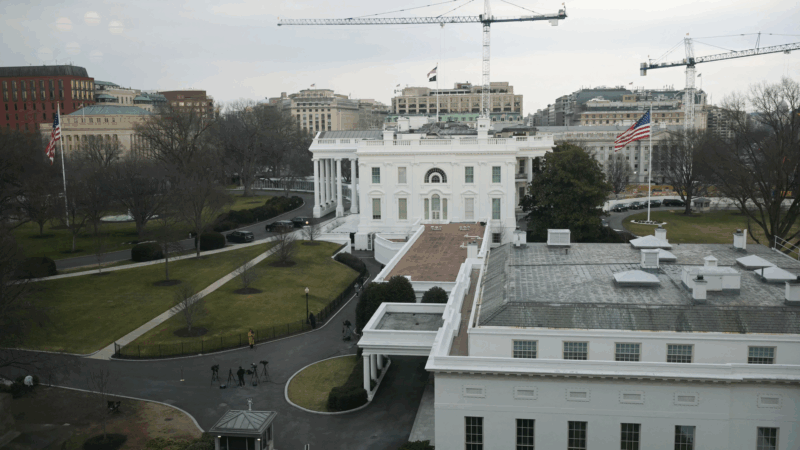

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

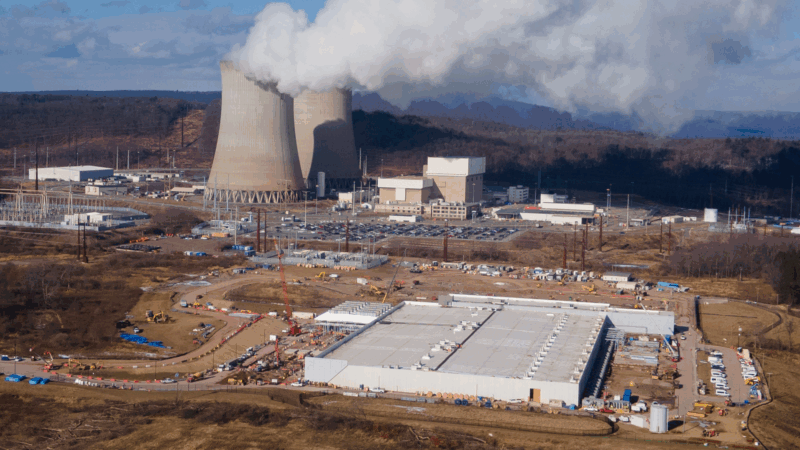

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.