Alabama looks to solve two problems at once by helping formerly incarcerated people enter the workforce

By Olivia McMurrey

More than 50 people on supervised release from Alabama’s prison system sat in folding chairs inside the Montgomery Day Reporting Center earlier this year. Speakers briefly addressed them, telling what to expect from the resource and job fair they were about to visit.

“Please learn all you can, put in the applications, make the day about you,” said Rebecca Bensema, assistant director for reentry with the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles.

“One other thing that I would say is, don’t let people judge you that didn’t get caught. Okay, hold your head up. Be proud. Let’s get some things done today.”

The event was part of an effort to bridge employment gaps and reduce recidivism rates in Alabama. The state incarcerates more of its people than most others, and when they’re released, those with criminal records struggle to find jobs – increasing the likelihood they’ll reoffend. Meanwhile, many businesses can’t find enough skilled workers.

Twenty vendors – many of them employers but also nonprofits that could help with food, housing and medical services – were part of the fair. J.F. Ingram State Technical College, which exclusively serves people who are incarcerated or on supervised release, organized the event.

On a mission

Most participants had a mission for the day – to get a job in a certain field or just to learn more about careers they could pursue. No one seemed more eager to take advantage of opportunities the resource fair offered than a woman named Kari. (We’re not using her last name out of concern it could affect her job prospects.)

As staff sorted participants into groups to navigate the event, Kari shared that her goal was to land a logistics job with Hyundai.

“It’s actually pretty cool how all the little parts gather together to make a bigger part that makes a bigger part that makes a car,” she said.

It quickly became clear Kari would be an excellent guide. She helped set up the day-reporting center for the resource fair, converting classrooms to spaces with tables lining walls in a horseshoe formation. She knew the drill – and the whole reentry system. This was her second time to navigate it.

People knew her, too. As her group meandered through hallways and rooms, she returned greetings from both fellow day reporters and those working for organizations represented at the resource fair.

One of them was her parole officer, Keiona Rogers, who had positive things to say about Kari.

“She has been flying through this program like there’s no tomorrow,” she said. “We have some clients that kind of struggle, and then we have some clients that just excel, and she’s one of those clients that have excelled.”

Rogers gave a tour of a long, rectangular room filled with racks of clothing donations – suits, dress pants, button-down shirts, blouses and more – along with belts and shoes.

Annette Funderburk, president of Ingram State Technical College, said employers not giving those with criminal records a chance is a well-known employment barrier, but the college’s students face many others – including not having the right clothing.

“Our men come out without a tie, and what a difference it is,” Funderburk said. “That’s one of the things that our instructors teach in our ACE Alabama essential learning soft skills class is how to tie a tie. Not only can they get a tie here, they can tie it here and they can go home with the tie.”

Reentry program provides education, support

While waiting to enter a room, Kari filled in details about the reentry program and the role of Ingram State, which is part of Alabama’s community college system and has 36 campuses located in prisons or day-reporting centers across the state. Kari took classes while serving 14 months at Julia Tutwiler Prison before being released to community supervision and the Montgomery Day Reporting Center’s reentry program.

“I do have to wear an ankle monitor,” she said. “We have a curfew. We have to do community service, and we come to classes every day to help us get ready to be out in this society and to reduce recidivism.”

Many people on supervised release acquired certificates, degrees and industry certifications through Ingram State while they were incarcerated. Kari was enrolled in the logistics and supply chain technology program. She said she took the classes and got the certifications she needed but didn’t graduate because the 12-month program is so popular there was a six-month wait to start it.

In addition to Ingram State’s career-prep and adult-basic-education classes, programs at the day-reporting center focus on substance abuse, mental health, anger management, financial literacy and more.

The first resource-fair stop for Kari’s group was a room with organizations that, among other things, assist those on supervised release in obtaining necessities for work that many people take for granted.

“Everybody doesn’t have a social security card or an ID or a birth certificate or anything they might need to actually get a job,” Kari said.

Back in the hallway, Kari said the reentry program is split into phases. In phase one, participants attend classes at the day-reporting center Monday through Friday. They aren’t allowed to work. Getting a job and working are priorities in phase two. Kari was finishing up phase one.

She introduced Steven, one of her classmates at the day-reporting center who still had two more weeks to go in phase one. (We’re also not using Steven’s last name out of concern for his job prospects.) He said he’s hoping to become a brick mason or equipment operator.

“I really like the program,” Steven said. “I’m getting a lot from it, but I’ll be happier when I move to phase two and get a job and start making some money, right?”

Obtaining transportation and housing without income is a challenge for many, Kari said, adding that the program connects those who ask for assistance with partnering organizations that can help.

When Kari stopped to catch up with Jade Gantt, a job placement coordinator with Ingram State, Gantt explained the reasoning behind phase one’s no-work rule.

“The phases assist them until they are ready to work,” she said. “It helps build their confidence and also their skills.”

And because they’re prepared, they’re more likely to keep a job once they get it, she said.

Ready to work

Funderburk said she wants employers to know Ingram State equips students to be responsible employees.

“It’s not just in reading and writing and learning how to weld or learning how to be a good carpenter or plumber, but it’s the soft skills,” Funderburk said. “It’s learning to be at work on time.”

When Kari made it to a room with employers, there was a line at the Hyundai table, so she visited others, including a heavy-duty truck manufacturer whose representative recommended she apply for a logistics job with a sister company.

The jobs being promoted in the room weren’t just any jobs. They were ones Ingram State and its partners in Alabama government and the business community have identified as high-wage, high-demand and open to the formerly incarcerated.

When Kari finally got to talk with the Hyundai rep, she had her elevator pitch ready.

“My resume is great for y’all,” she said. “I’ve got experience in several different plants that’s kind of like Hyundai as well as I’ve got my certifications.”

Candace Mabry, the Hyundai recruiter, seemed impressed. When asked why Hyundai chose to be a second-chance employer, she cited a shortage of automotive technicians and experience with the formerly incarcerated population.

“I’ve come across many managers that have seen better work ethic coming from those that have some type of record,” she said. “It’s even in the data that they actually tend to be better work performers. That’s something that I think a lot of companies need to shed more light on.”

Mabry told Kari to fill out an application on Hyundai’s career website, and she gave her a card with contact information.

Kari caught up with her group across the street, where a bright red and blue trailer was set up. Inside were rows of digital tablets on stands and screens showcasing high-demand jobs.

“Welcome to ALEX. We’re a mobile career expo,” announced Wayne Jennings, logistics manager for The Alabama Experience, a project of the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama. “On this side of the island, you can read about the careers, education needed. It has their average annual wage, their benefit package, total compensation.”

Jennings told attendees if they saw a career they were interested in, they could fill out a form on one of the tablets and ALEX staff would connect them with employers or trade unions in that field. Kari scrolled through options on a tablet and tapped on “heavy-equipment operator.”

“So in logistics at Tutwiler, we got to operate not only the forklift, but what they call a cherry picker, as well as a bulldozer,” she said. “I actually know how to do that.”

A model for success

Back inside the day-reporting center, everyone reassembled in the large room. There was one more task for the resource fair attendees: providing feedback on the event through a survey.

Kari put thought into her responses. As she filled out the survey, she shared that the reentry program wasn’t nearly so comprehensive when she went through it before. The day-reporting center had fewer staff and less programming, she said.

About five years ago, the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles started beefing up reentry programs at its 11 day-reporting centers and one residential facility. The goal was to cut Alabama’s three-year recidivism rate of 29% in half, and getting people into jobs that pay living wages is key.

Kari said she knows many people who turned back to crime because they couldn’t support themselves or their families. Statistics back up her lived experience. In the United States, the formerly incarcerated population has a jobless rate of approximately 60%, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. A 2008 study by the Safer Foundation, a Chicago-based nonprofit that provides reentry services, found that formerly incarcerated individuals who maintained employment for a year after release had a 16% recidivism rate over three years compared to the Illinois state average of 52%.

The resource and job fair at the Montgomery center will be replicated, said Bensema, with the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles.

“We are expanding these fairs throughout the state in an effort to bolster reentry and rehabilitation support services for the population that we serve,” Bensema said.

Kari didn’t get the job with Hyundai, but she did start working soon after the job fair. She’s set to graduate from the reentry program this month, and she’s looking forward to moving into her own place.

“I’ve got a fresh start,” she said. “And I’m just going to continue doing the right thing every single day.”

Her odds of sticking to that motto are good. The recidivism rate for those who graduate the reentry program is incredibly low. And while resources the program provides are available to a small fraction of people leaving Alabama’s prisons – partly because of transportation challenges many face in getting to day-reporting centers – the state wants to expand access.

That could ease worker shortages and create paths to stable employment for a lot more of Alabama’s former inmates.

US military airlifts small reactor as Trump pushes to quickly deploy nuclear power

The Pentagon and the Energy Department have airlifted a small nuclear reactor from California to Utah, demonstrating what they say is potential for the U.S. to quickly deploy nuclear power for military and civilian use.

How Nazgul the wolfdog made his run for Winter Olympic glory in Italy

Nazgul isn't talking, but his owners come clean about how he got loose, got famous, and how they feel now

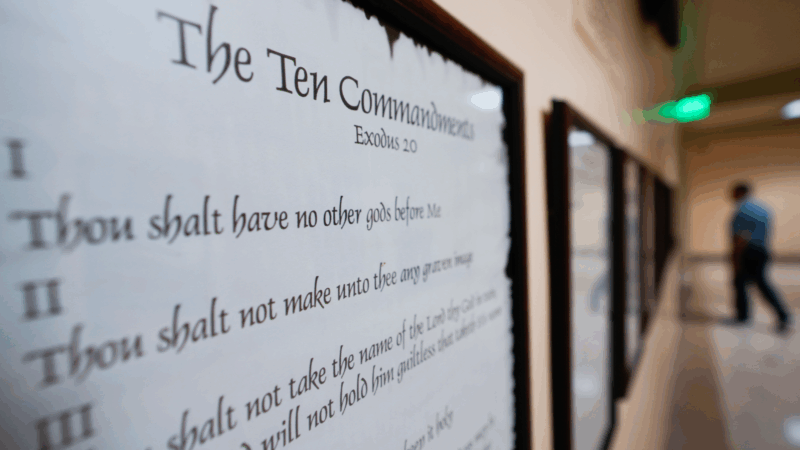

Court clears way for Louisiana law requiring Ten Commandments in classrooms to take effect

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has cleared the way for a Louisiana law requiring displays of the Ten Commandments in public classrooms to take effect.

From cubicles to kitchens: How empty offices are becoming homes

Many U.S. cities have too many office buildings and not enough homes. Developers are now converting some old offices into apartments and condos, but it's going slowly.

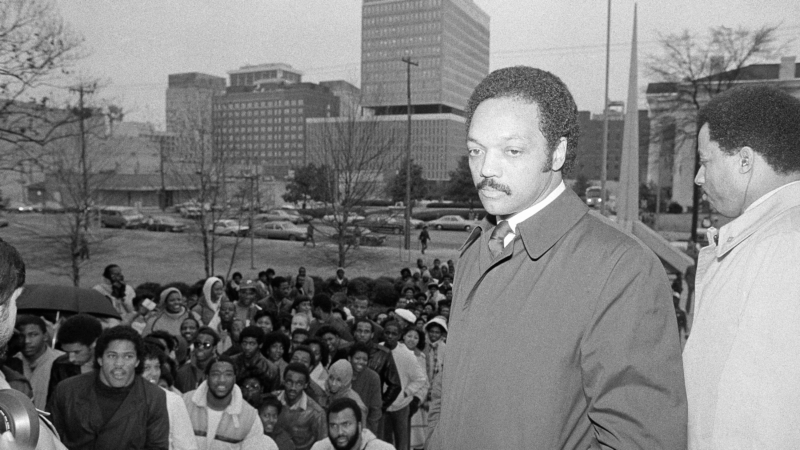

Opinion: The enduring dignity of Jesse Jackson

Rev. Jesse Jackson died this week at age 84. NPR's Scott Simon remembers covering Jackson's 1984 presidential campaign in Mississippi.

A huge study finds a link between cannabis use in teens and psychosis later

Researchers followed more than 400,000 teens until they were adults. It found that those who used marijuana were more likely to develop serious mental illness, as well as depression and anxiety.