20 years after Hurricane Katrina, East Biloxi’s casinos boom while Main Street dries up

Tyrone Burton stands outside of his barbershop in East Biloxi, Mississippi, on Aug. 14, 2025. Burton has cut hair in the same historically Black neighborhood for more than 60 years, even after his barbershop flooded during Hurricane Katrina.

Twenty years ago, Hurricane Katrina destroyed much of the Gulf Coast, including parts of the railroad that Amtrak ran a commercial line on, connecting New Orleans to Mobile, Alabama.

In mid-August, Amtrak resurrected this route — now dubbed the Mardi Gras Service. The Gulf States Newsroom’s Stephan Bisaha took part in the route’s inaugural trip.

Along the ride, he visited three coastal Mississippi cities that the route makes stops at to tell the story of how Katrina changed the Gulf Coast, and how these towns have worked to rebuild over the past two decades.

East Biloxi’s railroad tracks act like a line that divides the city economically, racially and in recovering from Hurricane Katrina.

East Biloxi received the worst of the damage in the larger city of Biloxi from Hurricane Katrina 20 years ago. The city says that about 80% of the area’s houses were either lost or made unlivable.

South of the railroad tracks were casinos that literally floated on the water. Mississippi law prevented them from being constructed on land, so they were instead built on barges. When Katrina’s storm surge came, the casinos moved with the flooding, in some cases, several blocks up.

Since then, those casinos have rebuilt — on solid land this time — and have boomed. Across Mississippi, casinos generate about $2.5 billion each year and employ about 16,000 workers.

But north of the railroad tracks, along Main Street, are several boarded-up, single-story homes. This section of East Biloxi is a historically Black district. Like many similar districts across the South, Jim Crow restrictions on where Black residents could shop meant these areas became a concentration of wealth within their community.

It’s where Tyrone Burton has been cutting hair for more than 60 years and still has his barbershop. He said this stretch of Main Street used to have a grocery store, laundromat, doctor’s office and other businesses.

“You didn’t have to go out and get a loaf of bread. All you had to do was walk across the street,” Burton said.

But many of those businesses have long left the neighborhood, and Burton said getting that loaf of bread now means traveling about 10 blocks.

A large part of that was because of the damage from Katrina, but Burton said the decline started well before that. Many historically Black districts struggled after desegregation, when the concentration of Black wealth became free to spend anywhere.

Desegregation also allowed those businesses to open elsewhere, and the decline began in the ‘70s and ‘80s, according to Allytra Perryman, program director at the East Biloxi Community Collaborative. She said the then-new Edgewater Mall on the far west side of Biloxi drew those business owners away from East Biloxi.

And in 2005, Katrina accelerated the neighborhood’s erosion.

“This area was completely drowned,” Perryman said. “The [Biloxi] Bay and the Gulf met. So there was no place in East Biloxi that was dry.”

The city of Biloxi recently renamed the stretch of Main Street by Burton’s shop to Tyrone Burton Way in his honor. But Burton said, to him, it looked like the city was just waiting for the neighborhood to dry up so they could take it and expand the city’s casino and recreation industry further north.

Biloxi created a comprehensive rebuilding plan that talked about reconstructing homes in East Biloxi. It points out the area’s environmental problems as a low-lying peninsula vulnerable to flooding. The economic challenges, such as the cost of rebuilding to flood risk standards, are combined with the area’s poverty. All this means new houses and people would likely continue moving north instead, the report predicted.

That’s what Burton has seen happen. Former residents took insurance checks, assuming they got any, and cashed them in to move north rather than stay and rebuild.

“The status right now is down, down,” Tyrone said about the neighborhood.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

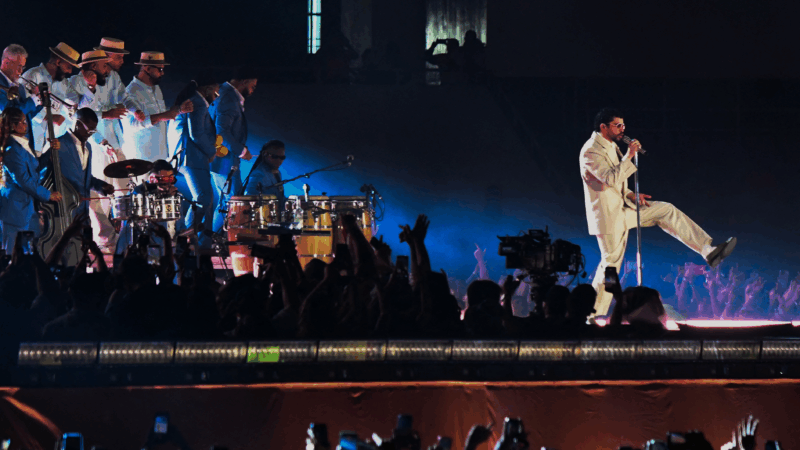

What you should know about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

Will the Puerto Rican superstar bring out any special guests? Will there be controversy? Here's what you should know about what could be the most significant concert of the year.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

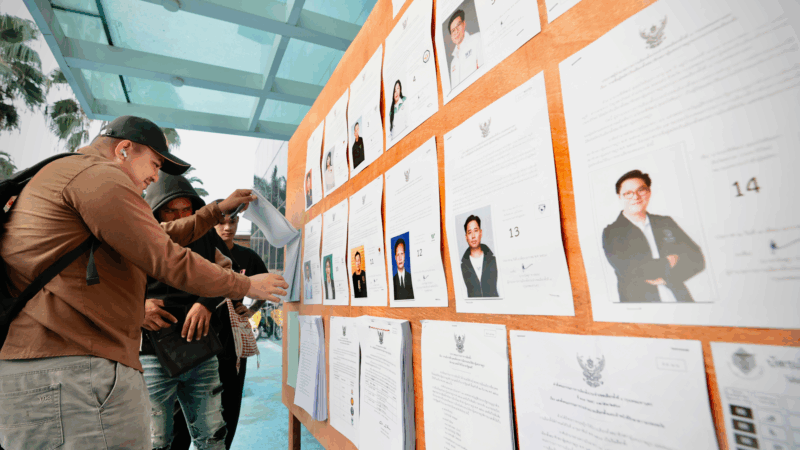

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.