These 3 farms are an example of Mississippi’s growing network of sustainable agriculture

An Alcorn State University student examines cherry tomatoes on Start 2 Finish Farm in Marks, Mississippi, on Wednesday, June 19, 2024. Farmers and students from Alcorn State University and other colleges visit Start 2 Finish to learn more about the sustainable practices used there.

Sustainable. Regenerative. Climate-smart. Whatever you call it, environmentally conscious approaches to farming are getting more federal support in the United States. In the Gulf South, some small farmers are taking advantage of the billions of federal dollars now available for climate-smart agriculture.

The Alliance of Sustainable Farms, a statewide network of small, mostly Black-owned farms in Mississippi, received $1 million from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Keith Benson, the organization’s executive director, hopes the funding will grow membership from 16 farms to more than 100. It will also help Alliance members use certified organic inputs, such as organic seeds or organic insecticide, and host demonstrations so other farmers can replicate what they’re doing.

“The logic is that they are demonstrating and promoting the adoption of all these innovative climate-smart conservation practices,” Benson said. “So, it’s going to be a lot of fun.”

Here are three farms in Mississippi using sustainable practices.

Davis Farm in Winona, Mississippi

Davis Farm is in Winona, about an hour north of Jackson. The owner, John Paul Davis, tends to around six acres of land he owns, growing watermelons, zucchini, squash, blackberries and many other crops. He also manages an additional two acres of purple hull peas.

Davis wasn’t always a farmer. For decades, he was a deputy sheriff in his home, Montgomery County. After that, he worked a variety of state jobs before deciding he wanted to be his own boss.

“I talked to some of my friends and they said, ‘Man, you need to just start farming,’” Davis said.

His kids had other ideas. When he started farming, Davis said, with a laugh that they thought, “Daddy done lost his mind.”

Before long, he started attending field days hosted by the Alliance of Sustainable Farms. There, Davis learned about ways to produce more while using fewer resources.

For him, sustainable agriculture means not using pesticides and using less water with a special type of irrigation that gets water directly to the roots. He thinks it makes his crops healthier, and that’s important to him.

“Because one thing about it, I eat it first,” Davis said.

He also uses two high tunnels — covered structures that allow farmers to grow year-round. It took patience to get them, however.

He applied for his first one in 2014 but didn’t get an answer until 2017. By then, he had almost given up. The second tunnel came faster: he applied in 2022 and received a letter letting him know he qualified in 2023.

“You gotta have patience, ‘cause the government is going to do what they going to do when they want to do it,” Davis said.

Brewer Vegetable Farm in Greenwood, Mississippi

The Alliance helps farmers with monthly training, like how to use landscape fabric to suppress weeds instead of pesticides. They also have “anchor farms,” or farms that have experience with sustainable practices and equipment to share.

That’s where people like James Brewer, a vegetable farmer in Greenwood, Mississippi, come into play.

Brewer uses a peas shelling machine at his farm — Brewer Vegetable Farm. Rather than every farm buying its own pea sheller, Brewer allows other farmers to use his. Benson said the farmers also share more expensive equipment, like tractors or harvesters.

Alliance members share resources this way because it’s harder for small farmers to have the money to afford what they need.

Small farms are the majority of producers in the U.S., but large-scale farms make up most of the country’s farm income, according to the USDA.

“When I hear stuff like that, what it says to me is groups like the Alliance and others have to do a better job of accessing those resources,” said Keith Benson, the Alliance’s director.

Brewer jokes he got into the Alliance because Benson is a smooth talker. He started farming in 2014, raising peas, okra, tomatoes, cucumber, squash, many greens and anything else people request.

Since joining the Alliance, he’s learned to appreciate the resources it provides.

“You get to meet a whole lot of people and get to do a whole lot of things,” Brewer said. “If you need something, if you talk long enough, [Benson will] provide it for you.”

Brewer’s start in farming stems from his five children, for whom he started a garden so they could eat. Since then, he’s grown a group of loyal customers, including one older man who has bought peas from him for years. One day, the man decided to tell Brewer how he felt about them.

“He said, ‘Them the best peas I’ve ever ate, and I’ma buy peas from you until I die.’ And that’s the type of comments that I love to hear,” Brewer said. “It makes me want to stay out here all day and all night.”

Start 2 Finish Farm in Marks, Mississippi

Robbie Pollard owns Start 2 Finish Farm in Marks — in the Mississippi Delta.

He started farming in 2019, mostly teaching himself through YouTube videos. Now, he’s also an anchor farm for the Alliance, which includes hosting field days.

Over the summer, he shows his farm to a group of farmers and students from Alcorn State University and other colleges to learn more about climate-smart agriculture. Some techniques he implements on his farm are irrigation management, by using drip irrigation, and nutrient management, by not using chemical pesticides.

He also works with other farmers who are part of the Alliance’s “cluster farms,” or farms that grow a lot of the same types of food and then sell them as a collective to attract a bigger market.

Pollard has also started a food initiative called the Happy Foods Project. The idea is to start a community-supported agriculture program that makes fresh food accessible to local communities.

“You really want to give people the healthiest food that they can get to,” Pollard said.

As he harvests crops like tomatoes and eggplants, Pollard says these practices are a return to the basics. Throughout history, many Black farmers have used techniques that are considered sustainable, or regenerative, such as growing a variety of crops to improve soil health.

“We’re been doing regenerative ag before it was a thing,” Pollard said. “We’re able to get some funding for some of the stuff that we are already doing, so that’s a good thing.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Shootings at school and home in British Columbia, Canada, leave 10 dead

A shooting at a school in British Columbia left seven people dead, while two more were found dead at a nearby home, authorities said. A woman who police believe to be the shooter also was killed.

Trump’s EPA plans to end a key climate pollution regulation

The Environmental Protection Agency is eliminating a Clean Air Act finding from 2009 that is the basis for much of the federal government's actions to rein in climate change.

From gifting a hat to tossing them onto the rink, a history of hat tricks in sports

Hat tricks have a rich history in hockey, but it didn't start there. For NPR's Word of the Week, we trace the term's some 150-year-history and why it's particularly special on the hockey rink.

Pam Bondi to face questions from House lawmakers about her helm of the DOJ

The attorney general's appearance before the House Judiciary Committee comes one year into her tenure, a period marked by a striking departure from traditions and norms at the Justice Department.

The U.S. claims China is conducting secret nuclear tests. Here’s what that means

The allegations were leveled by U.S. officials late last week. Arms control experts worry that norms against nuclear testing are unraveling.

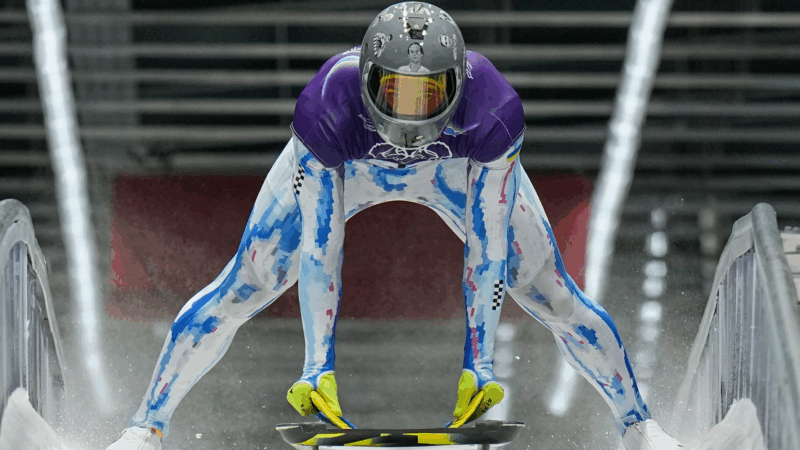

Ukrainian sled racer says he will wear helmet honoring slain soldiers despite Olympic ban

Vladyslav Heraskevych, a skeleton sled racer, says he will wear a helmet showing images of Ukrainian athletes killed defending his country against Russia's full-scale invasion. International Olympic Committee officials say the move would violate rules designed to keep politics out of the Olympics.