One-day strikes are in: Why unions are keeping it short on the picket line

Strikes can be long, grueling wars of attrition to see who blinks first — the workers or the employer.

They can also be a party.

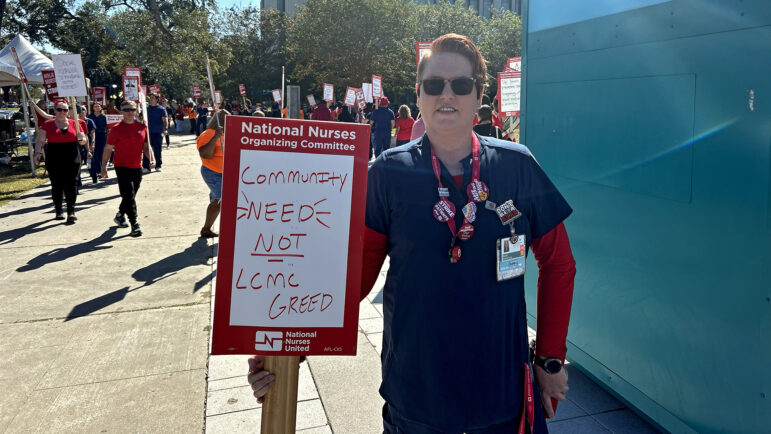

Nurses from LCMC Health System’s University Medical Center New Orleans went with the latter in October. Their picket line included a stage, live music and a DJ in front of the university hospital’s campus.

“It’s multiple holidays rolled into one,” said Terry Mogilles, a nurse at the hospital’s trauma orthopedic clinic. “Mardi Gras. Christmas. Birthday.”

Another way strikes can be different? Keeping them brief. This strike was scheduled to only last 24 hours. While long-running strikes have dominated the headlines in the Gulf South region in the past few years, short strikes have become the norm. Since at least 2021, most strikes have lasted less than five days, according to the labor action tracker run by Cornell University and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The majority of those short strikes last no more than a day.

The reason for this is, short or long, strikes are double-edged swords that cut both employer and employee. Keeping them short means wielding a duller blade, causing less pain to both sides while also sending the signal that workers should be taken seriously.

Workers with enough leverage can still use their blunted weapon to win major concessions. But the track record of these defiant blips is mixed. While they’re meant to reshape the balance between workers and their bosses, their use instead of longer demonstrations shows just how much the scales have slid to the C-suite.

Even for one day, nurses have leverage

The UMC nurses unionized in late 2023 to negotiate for a safer workplace, a pay bump and to push the hospital to hire more nurses.

A year later, the nurses were still negotiating.

They sent the hospital a 10-day notice in October to warn of their one-day strike. The nurses said they kept the strike to 24 hours to minimize harm to patients, along with their own paychecks. By comparison to a traditional strike — which can last weeks, months or years in some cases — one day without pay doesn’t sound so bad.

But even a one-day strike causes disruption, especially for a literal life-and-death job like nursing.

UMC New Orleans CEO John Nickins said he was disappointed in a YouTube video posted before the strike, criticizing the nurses for abandoning patients. He repeated the phrase, “One day matters.”

Still, the nurses say the CEO’s message proved their point by demonstrating the value of their labor. It also showed the nurses have a key advantage in a negotiation: leverage.

“If you have that type of enormous leverage that you inflict huge economic pain or a huge amount of distribution by going out on a one-day strike, they are still very effective,” John Logan, chair of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University, said.

The hospital hired expensive temporary nurses so it could stay open and ended up locking out the striking nurses for two more days since agencies for temporary nurses often only offer services with three days of promised pay.

Nurses aren’t the only type of workers with this kind of leverage. In 2016, Philadelphia International Airport workers threatened to go on strike during the Democratic National Convention, which the city was scheduled to host. They wanted American Airlines to get out of the way of workers trying to unionize. The airline caved.

“The prospect of having a labor strike at an airport where DNC members are going to have to cross picket lines immediately led to a situation where American Airlines was willing to come and talk to the union about recognition and bargaining,” Stuart Eimer, associate professor at Widener University, said.

Short strikes are all some workers can afford

So, what about workers without that kind of leverage?

In part, the popularity of the one-day strike over the last decade was a response to unions losing leverage and power.

In the 70s and 80s, huge economic changes like globalization and deregulation left unions weakened, according to Logan. Companies began demanding concessions from workers and permanently replacing workers when they went on strike. This led to a huge drop in the number of work stoppages for decades.

“Unions kind of began to view strikes as almost as economic suicide,” Logan said.

The Fight for 15 movement, a campaign to raise pay for low-wage workers and unionize them in the 2010s, did rely on strikes, but ironically, the low wages the movement was trying to change also meant workers couldn’t afford to go on long, indefinite strikes.

The answer to this dilemma was the short strike. Fight for 15 held multiple one-day strikes across the country with fast food workers. The actions drew national attention and led to several states raising their minimum wages. In recent years, Starbucks baristas have been the one-day strike trendsetters.

Building up morale

When it comes to getting employers to cave to demands, the success of one-day strikes is mixed — especially for those low-wage, low-leverage workers. Short work stoppages failed to unionize Walmart in the 2010s, along with those fast food workers from Fight for 15. Starbucks and its unionized employees are still negotiating a first contract.

Long strikes are still happening — just ask SAG-AFTRA — and probably won’t be phased out entirely because they still carry much more leverage.

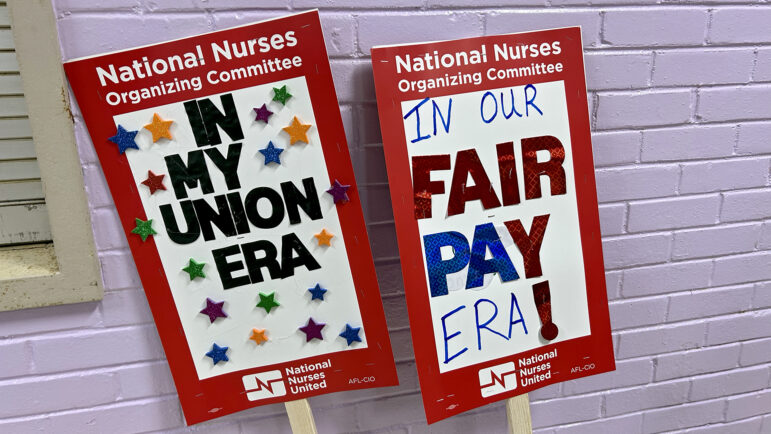

Instead, one-day strikes often have a different goal in mind that’s still essential for a union victory — getting workers excited.

Union campaigns and negotiations can be a slog that can take years without any guarantee of success, and those chances dwindle if workers are disengaged. Short strikes get workers active and feeling like they’re involved while negotiators go through the long, detail-hammering process.

Short strikes also let workers get media and national attention without the pain that comes from a long stoppage. The UMC nurses said it wasn’t a coincidence their strike happened the same weekend as a Taylor Swift concert. As Swift fans drove past the picket line party, they honked their horns in support.

“I’m really proud of everyone for showing up,” said nurse Dana Judkins. “Hoping some Swifites see us and maybe post it to their story. More nationwide news.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Trump’s many tariff tools mean consumer prices won’t go down, analysts say

The Supreme Court struck down President Trump's signature tariffs. But the president has other tariff tools, and consumers shouldn't expect cheaper prices anytime soon, economists say.

Hundreds of American nurses choose Canada over the U.S. under Trump

More than 1,000 American nurses have successfully applied for licensure in British Columbia since April, a massive increase over prior years.

5 takeaways from Trump’s State of the Union address

President Trump hit familiar notes on immigration and culture in his speech Tuesday night, but he largely underplayed the economic problems that voters say they are most concerned about.

China restricts exports to 40 Japanese entities with ties to military

China on Tuesday restricted exports to 40 Japanese entities it says are contributing to Japan's "remilitarization," in the latest escalation of tensions with Tokyo.

Signs, silence, and skipping: How Democrats protested Trump’s State of the Union

The pushback comes as Democrats enter a midterm year where they hope to make gains in the House and Senate.

Trump honors gold medal-winning men’s hockey team at State of the Union amid controversy

The celebration of the men's team comes after FBI Director Kash Patel's trip to the Games in Milan, and the president's comments about the U.S. women's team, have drawn scrutiny.