Mixed reaction to anti-crime program which blocks some Birmingham streets

By Sara Güven, Reflect Alabama Fellow

Streets in Birmingham’s East Lake neighborhood are now blocked by brightly painted concrete barriers and houseplants in a new effort by Mayor Randall Woodfin to reduce crime.

They’ve been placed there by the mayor’s office as part of a new initiative in a neighborhood plagued by shootings, drug dealing, prostitution and more. The effort, called Safe Streets, launched at the beginning of July. The program also includes traffic calming measures and garbage cleaning efforts.

According to Woodfin, reducing access to the area and cleaning dilapidated streets will make it more difficult for people to conduct illegal activities. He said the effort is informed by data from cities across the country that have implemented similar methods.

Woodfin said extensive surveys were conducted with residents through a door-knocking campaign. He said his office spoke to 350 residents inside the barriers, with 90% of them supporting the plan.

However, residents who spoke with WBHM offered a range of opinions on the initiative.

Mimi Freeman, an East Lake resident for 14 years, strongly approved of the barricades. She said criminal activity has worsened over time.

“It was not this bad in crime when I was younger. You had the occasional robbery, maybe a car break-in, something like that,” Freeman said. “But it was never this bad where it was a murder, a killing, a drive-by shooting every single day of the week.”

She appreciated the effort, and wants more barricades to be put up.

Darell Nance, who’s lived in East Lake for six years, was grateful for Woodfin’s attempt to address the neighborhood’s issues, but questioned if barricades were the most effective means to do so.

“A lot of the efforts, I think could be achieved without putting a bunch of barriers in place and making residents feel like they’re locked in,” Nance said.

He worried the barricades will not do enough and that the attention on the neighborhood will fade.

“I feel like we’re going to get 90 days of attention and then this is going to fall off and it’s going to be back to business as usual type of thing,” Nance said.

Russell Hooks, a resident since 2019, initially had some concerns.

“I joked, as long as it’s not Escape from New York, where they just block off the neighborhood and just let everything inside that neighborhood happen,” Hooks said.

He’s since grown more willing to consider the barricades as a solution, especially since they are accompanied by other efforts. Still, he preferred a different solution for the long term.

“My hope is that it won’t be permanent. They can do the pilot program, maybe do a little bit longer, and at some point, figure out a different solution – just for the convenience of having the roads open,” Hooks said. “But I definitely understand why they did it the way they did, given the limited resources of the (police) officers.”

Jason Hameric shared a similar view. He opposed the barricades and said they make their neighborhood seem like a prison.

“If you isolate people and make them feel like they’re around walls, they have nothing to expect but that,” he said.

Hameric said he’s lived in Birmingham all his life, but felt the issue of crime has him considering leaving.

“When my wife and I decided to buy a house and start a business, we wanted to make sure that Birmingham got our tax money because we believe in the city. And we stayed here for that reason,” Hameric said. “It’s the first time we’ve ever thought about taking our business and our house somewhere else, because we feel like it’s on a downward spiral.”

Residents said they have seen a decrease in traffic, but noted that traffic may have shifted to other streets. Some residents expressed concern about the barricades’ effect on property value.

The barriers will remain in place until October, the end of the pilot phase. After that, the program will be evaluated to determine next steps.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

U.S. states take steps to guard against any potential threat from Iran

Iran has made prior attempts to launch terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, but all have been thwarted in recent years. States are bracing for a heightened threat after the war.

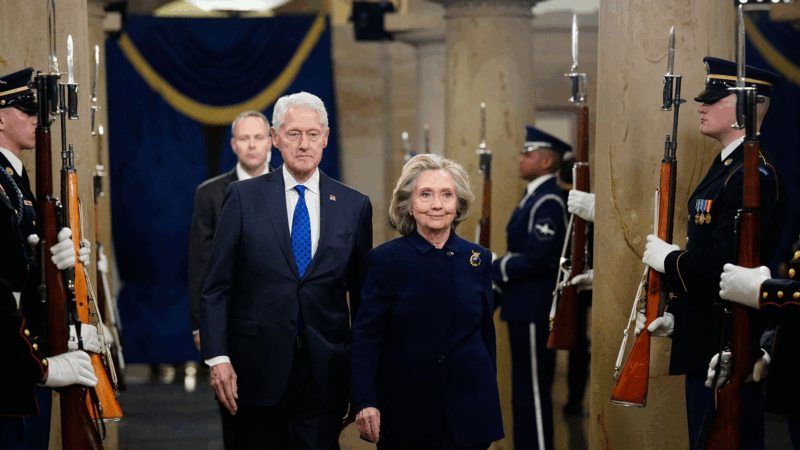

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.