Here are 3 questions to ask before panic buying during a supply chain breakdown

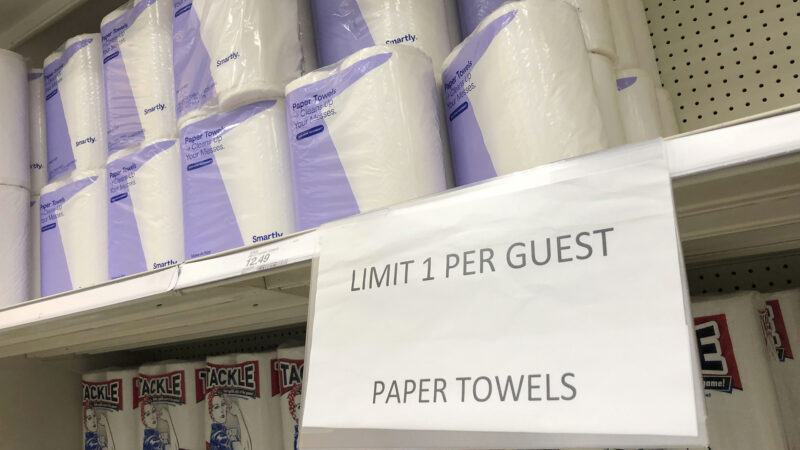

A sign indicates a limit on purchases of paper towels in a Target store in this file photograph taken Tuesday, Nov. 10, 2020, in Sheridan, Colo.

It was a pandemic déjà vu in early October: empty toilet paper shelves.

The International Longshoremen’s Association strike that shut down ports along the South and East Coast only lasted a few days, but that still led to reports of panic buying across the country.

There’s a chance that happens again.

The union and the United States Maritime Alliance have a tentative agreement to continue negotiations until mid-January, but without a deal, a new strike could take place by then. There are also other potential triggers for panic buying in the future, including natural disasters like hurricanes or even another pandemic.

This is why the Gulf States Newsroom has put together what we’re informally calling the “Shopper’s Guide to a Supply Chain Breakdown: Panic Free Edition.”

This crisis guide is less a catalog of products to buy or skip and more of a mindset — a series of questions to ask before running to the store or filling your online shopping cart.

Is it made domestically?

In the case of global trade disruption, like another dockworkers’ strike, the first question to ask is if what you’re looking to buy is made domestically. If so, you can leave it on the shelves.

Possibly the best example of this is toilet paper.

Most toilet paper consumed in this country is made in the United States, so shut-down ports should not lead to any significant shortages. Paper and pulp production is actually big business in Southern states, like Mississippi and Alabama. The Port of Mobile exported $1.6 billion in paper products in 2022.

Yet there were still toilet paper shortages during the strike, at least at some stores — caused by shoppers’ overreaction rather than the strike.

Glenn Richey, research director at Auburn University’s Center for Supply Chain Innovation, said that’s due to what’s called the “bullwhip effect.” One shopper cautiously buying a few extra rolls of double-ply isn’t a big deal, but if all shoppers across the country think the same, it leaves stores and supplies scrambling to meet the demand spike.

That was part of the reason behind the pandemic toilet paper shortage, too.

Was there prep time?

After turning an eye away from domestic products, imports deserve a glance. That includes pharmaceuticals and medical devices — even active ingredients often get imported.

But pharmaceutical companies often have about 180 days of inventory on hand, according to Terry Esper, a professor researching logistics and supply chain management at Ohio State University. He said the pandemic caused companies to switch from the “just in time” economy, where companies only have goods and materials show up at stores and factories right when they’re needed, to the “just in case” economy.

“If there was a silver lining to the pandemic, it would be that most companies have really taken a different approach to be much more proactive about making sure that they keep inventory within and across their supply chains,” Esper said.

Unfortunately, that kind of prep doesn’t help in the case of a common type of import — perishables.

Bananas are an example of a fresh fruit that’s almost exclusively imported and that could have gone missing from stores if the strike lasted for more than a few days.

How much do you actually need?

Of course, there’s not much prep time when the supply chain crisis comes from a natural disaster, like a hurricane. Questions about imports and exports can also be forgotten while the biggest disruption comes from damaged roads and buildings.

In the case of a bad storm, it does make sense to stock up on products like toilet paper, just don’t buy up the whole aisle.

Companies like Walmart hire meteorologists to track storms, so they know where to move supplies to quickly stock a store back up post-disaster.

There’s little companies can do to prepare if a natural disaster hits somewhere a major supplier of a vital product is located, however, like when Hurricane Helene destroyed a major IV fluid manufacturing facility in North Carolina — causing lingering IV shortages.

Still, Esper says disruptions like that are the exception that average shoppers shouldn’t worry much about.

Instead, his big tip for customers during a crisis is: “Buy. Don’t panic.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

This historian dug up the hidden history of ‘amateur’ blackface in America

In her new book, Darkology, historian Rhae Lynn Barnes writes about how blackface and minstrel shows became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in 19th- and 20th-century America.

Attempted attack with explosives in New York City investigated as “ISIS-inspired terrorism”

New York City NYPD Commissioner: "Explosive devices that could have caused serious injury or death."

Trump is using immigration policy to suppress speech, lawsuit claims

A new lawsuit accuses the administration of violating the First Amendment by threatening the visas of researchers for work on disinformation and content moderation of social media.

Why young girls are disguised as boys in Afghanistan

The Taliban has released a video of an interrogation of a girl who passed as a boy. It's an age-old practice in this patriarchal society but now appears to be happening with some frequency.

Live Nation and Justice Department reach settlement in antitrust case

The trial, which began a week ago in a New York City courtroom, aimed to break up Live Nation and its subsidiary, Ticketmaster.

Microshelters for Birmingham’s unhoused set to open soon

The pilot program called Home For All involves building 14 small pallet homes to house those who would otherwise be living on the streets.