Alabama leads US in ‘pregnancy criminalization’ cases following Dobbs decision: report

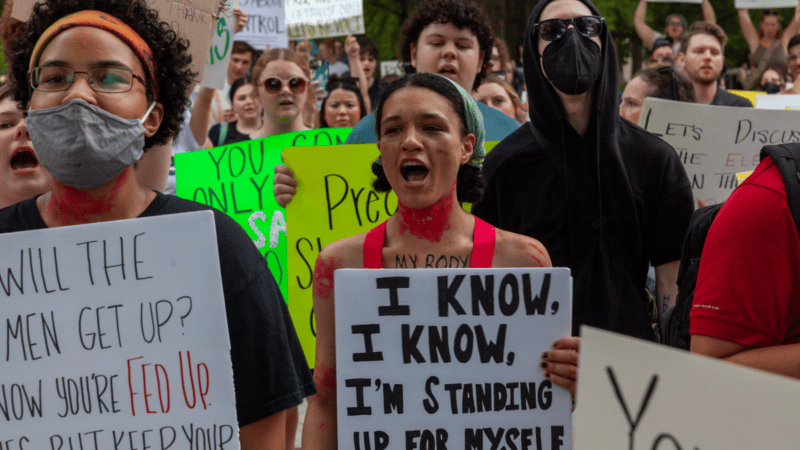

A crowd chants during a protest against the Supreme Court's ruling overturning Roe v. Wade on Saturday, June 25, 2022, in Birmingham.. Several hundred people massed in Linn Park for a rally organized by the Yellowhammer Fund which provides financial assistance for people seeking abortion care. (Photo by Rashah McChesney/Gulf States Newsroom - WBHM)

As prosecutors in a dozen states charged women with crimes related to their pregnancies, the Gulf South accounted for more than half of known cases, a recent study found.

The preliminary review from the legal defense and policy group Pregnancy Justice tracked such prosecutions for a year following June 24, 2022 — after Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court decision that overturned the constitutional right to abortion.

For the period researchers examined, they unearthed more than 100 cases of prosecution in Alabama — nearly half the total — plus a handful in Mississippi. Cases also were found in several other states, including Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas.

Most cases the group found pertained to alleged drug use during pregnancy, not abortions. But the findings help shed light on the use of criminal laws informed by the idea of fetal personhood, a legal premise gaining traction in the South.

“Fetal personhood” proponents argue that such statutes protect the rights of the unborn. The report’s authors contend that they’re used for “controlling and punishing” pregnant people.

In Alabama, “we have these women who were abusing substances while pregnant,” explains Brittany VandeBerg, a University of Alabama criminal justice professor who worked on the study. “And even if the child has no harm after they’re born, they’re still getting charged with these charges.”

VandeBerg said a call to law enforcement is sometimes initiated by hospital staff as a result of a positive drug test for someone who is pregnant or giving birth. That can set a chain of events in motion that leads to prosecution and potential imprisonment.

Her team has found that in Alabama, people being prosecuted are often poor white women from rural communities. They may be struggling with addiction but live in areas that lack resources for treatment.

She said they’re unlikely to have resources to pay bail or for a private defense attorney, and can end up sitting in jail or serving time in prison.

“I’ve spoke[n] with some law enforcement officers in these rural counties, and they have expressed their frustration,” VandeBerg said. “They say, well, we don’t want to be arresting these women.”

Limitations to the study included the “notoriously opaque” U.S. criminal justice system, which lacks centralized records across jurisdictions and states. Researchers thought their findings were likely an undercount.

While they’d identified more cases than in any previous calendar year, they could not determine definitively whether these prosecutions were occurring more frequently or if their searches were more effective — “the team suspects it may be both,” they wrote.

The report’s authors recommend investments in resources for treating substance abuse in pregnant people, rather than taking a “punitive” approach to addiction.

They also advocate for expanded privacy protections in health care settings, including drug test consent rules, and that states work to enact laws to shield people from being charged with crimes related to their pregnancies.

VandeBerg said research has continued and that they’re seeing cases pop up in new Alabama counties.She said what’s happening could prevent women from reaching out to health care services, out of fear of being reported to law enforcement.

“If our whole goal is to protect children and unborn children, I feel like this is doing exactly the opposite of what we want,” VandeBerg said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.

They’re cured of leprosy. Why do they still live in leprosy colonies?

Leprosy is one of the least contagious diseases around — and perhaps one of the most misunderstood. The colonies are relics of a not-too-distant past when those diagnosed with leprosy were exiled.

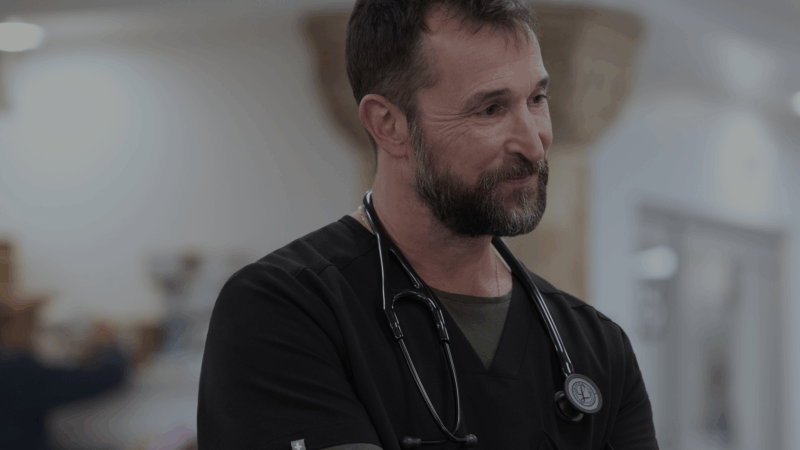

This season, ‘The Pitt’ is about what doesn’t happen in one day

The first season of The Pitt was about acute problems. The second is about chronic ones.