Alabama Black Belt’s sewer crisis a tougher fix for residents in manufactured homes

Willie and Thelma Perryman sit with their young grandson in the front yard of their home on Wednesday, October 30, 2024, in Letohatchee, Alabama. The Perrymans are seeking a new septic system to deal with their sewage issues.

Willie Perryman pulls up to his manufactured home in Letohatchee, Alabama. He was down at his church, helping distribute food, but had to come back to meet with the Black Belt Unincorporated Wastewater Program (BBUWP), a local nonprofit visiting his home to check out his sanitation situation.

As he exits his vehicle, his wife, Thelma, calls out to him.

“You ain’t have to leave your post,” she said. “We had everything under control.

The Perrymans have known each other for over 60 years. They often travel around the community, helping out the elderly and disabled. But though they help others, the Perrymans are also dealing with a big problem of their own: sewage issues.

They live in a manufactured house that doesn’t have a septic system. Instead, a pipe leads out of the house and dumps sewage on the ground — what’s known as “straight piping” — running down a hill and leading into the nearby woods. They won’t let their young grandson wander alone.

“Hold up!” Thelma Perryman calls out to her grandson, stopping him from running to the backyard unsupervised. “You know you don’t go there by yourself. And stop picking up leaves.”

The Perrymans have spent the past 22 years living with this type of sewage disposal. They’re looking for a new septic system, but a few barriers stand in their way.

Poor sanitation has long plagued residents in Alabama’s Black Belt, named for the region’s rich, black soil. While great for agriculture, this same soil isn’t absorbent. This causes traditional septic systems to not work properly.

Thelma Perryman has dealt with bad sewage for as long as she can remember.

“When I was growing up we had what’s called an outhouse. And when I moved to the other trailer, we had a septic tank, but it always ran over,” she said. “So we’ve been having problems with sewage practically all my life.”

Sometimes, there’s a bad smell, and the Perrymans have to keep their doors closed to keep it out of the house. Other times, their system backs up and they have to plunge it out.

“Well, I got used to it, but I would like to do better,” Thelma Perryman said.

The Perrymans aren’t the only family fighting this issue. In the Black Belt, roughly 1 in 4 homes is a manufactured house. Many are in rural communities, meaning they aren’t within city limits, and residents have to provide their own sanitation.

“The residents can’t afford the water and waste treatments or services that they need,” said Stephanie Wallace, the project manager for the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice (CREEJ) in Alabama.

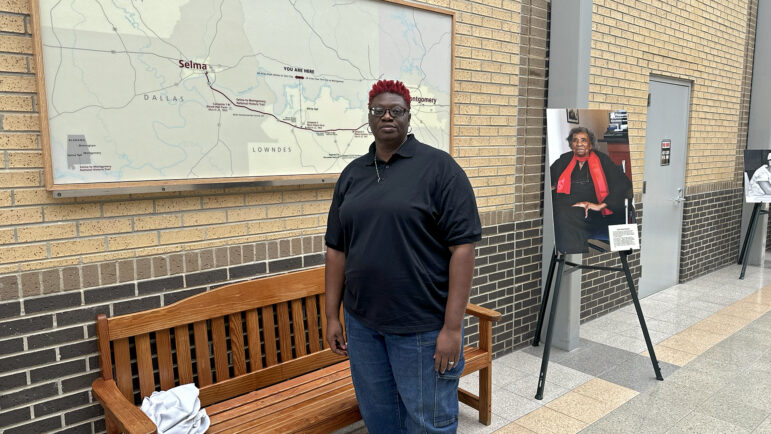

CREEJ was founded by Catherine Coleman Flowers, a Lowndes County native.

Like Perryman, Wallace, a lifelong resident of Lowndes County, has grown up dealing with raw sewage piling up on the ground. She remembers being a child and not being able to play in a certain part of the backyard of a friend’s grandma’s house because raw sewage was leaking from the pipes onto the ground.

“For me, in my childhood experiencing it, and now in my adulthood still experiencing the same things, something has to change,” she said. “It has to get better for future generations. Because at this stage in life, we shouldn’t still be experiencing those same things.”

Wallace began working with CREEJ almost 20 years ago. During that time, she saw how housing issues intersect with wastewater issues.

“I got to see how they were helping people in the community with wastewater issues. A couple of those families were also living in unsuitable housing,” Wallace said.

Many people who live in manufactured homes do what the Perrymans do and let the sewage go on the ground, Wallace said, because Alabama was loose in making sure mobile homes comply with certain codes.

Some homeowners do have septic systems, but they are failing because the soil isn’t right for the kind of system they have. Specialized systems can cost tens of thousands of dollars, which is money that many in the region don’t have. In Lowndes County, the poverty rate is more than 25%.

Unlike a traditional site-built home, mobile homes don’t increase in value — decreasing in value similar to cars — which can keep people locked in poverty.

“A lot of the agencies at the state level that could help them haven’t been helping,” Wallace said.

Last year, CREEJ and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) filed a Title VI Civil Rights Act complaint against the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM) and the State of Alabama, alleging that how the state distributes funding for wastewater infrastructure hurts Black communities.

The state’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund doesn’t allow individuals to apply for its low-interest loan program for infrastructure improvements. But that’s changing, following an interim agreement the Alabama Department of Public Health signed with the U.S. Departments of Justice and Human Services last year concerning sewage disposal issues in Lowndes County.

Since then, the health agency started a program to install septic systems that can properly dispose of onsite sewage.

At least two local nonprofits are tackling the issue of sanitation — the BBUWP and the Lowndes County Unincorporated Wastewater Program (LCUWP).

Thelma Perryman’s family reached out to BBUWP to see about getting a septic system, but that led to another issue — the condition of her family’s aging home.

They have damage from a felled tree limb, and one side of the house is propped up with boards because it’s rotted away.

A new system would cost more than their home is worth, and the nonprofit said they need a new house. Willie Perryman agrees.

“I would like a second-hand trailer before the sewage get did, but we’ll take either or,” Willie Perryman said.

But despite their issues, Willie Perryman said he couldn’t imagine moving away. The Perrymans live on family land that Willie’s family has had for more than 100 years. It fills him with pride. His grandfather had 24 children, and he raised all of them here.

Willie Perryman would like to pass this land down and keep that legacy. In the meantime, the Perrymans are waiting to see if they can get a new home, or a new septic system.

“That’s what I would like to do while I’m here on this earth,” Willie Perryman said. “I’m proud now because we’re still here.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. This story was produced with support from the Environmental and Epistemic Justice Initiative at Wake Forest University.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

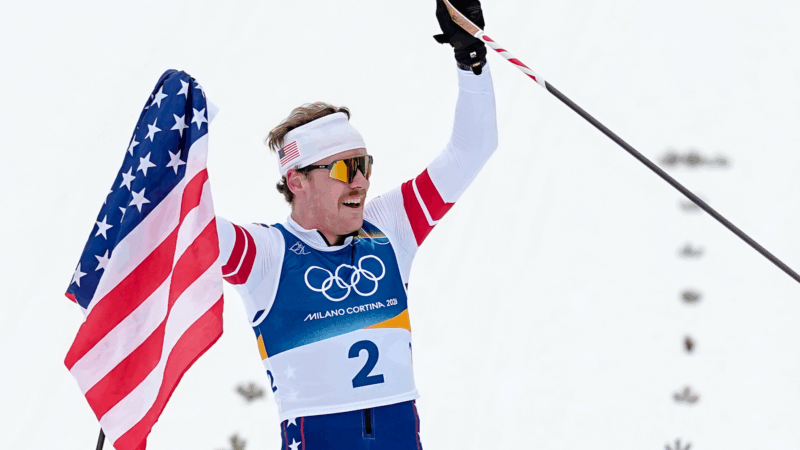

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.

An ape, a tea party — and the ability to imagine

The ability to imagine — to play pretend — has long been thought to be unique to humans. A new study suggests one of our closest living relatives can do it too.

How much power does the Fed chair really have?

On paper, the Fed chair is just one vote among many. In practice, the job carries far more influence. We analyze what gives the Fed chair power.

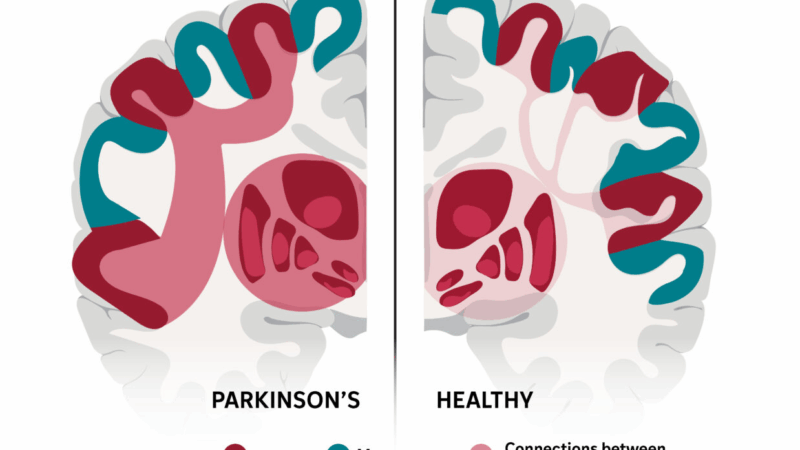

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.

‘Please inform your friends’: The quest to make weather warnings universal

People in poor countries often get little or no warning about floods, storms and other deadly weather. Local efforts are changing that, and saving lives.