A new EPA grant is sending millions to the Alabama Black Belt to solve sanitation issues

In this file photo, heavy rains flood the front yard of Lowndes County resident Charlie Mae Holcombe, Feb. 21, 2019, in Hayneville, Ala. The U.S. Department of Justice on Thursday, May 4, 2023, said an environmental justice probe found Alabama engaged in a pattern of inaction and neglect regarding the risks of raw sewage for residents in the impoverished Alabama county and announced a settlement agreement with the state.

More than $14 million will go toward installing onsite wastewater treatment systems in Alabama’s Black Belt region as part of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Community Change Grants Program.

The systems will treat 350 homes in Hale, Lowndes and Wilcox counties, where poor sanitation is an ongoing problem that’s gotten national and governmental attention. The Black Belt communities have struggled from historic disinvestment in infrastructure, said Amal Bakchan, an assistant professor with Texas A&M University, the lead project applicant.

“These communities deserve to have access to clean water and well-treated wastewater services,” Bakchan said.

Funding for the project comes from more than $325 million the Biden-Harris Administration earmarked to help disadvantaged communities tackle environmental and climate justice challenges as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, often touted as a “once-in-a-generation” move to improve the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, storing carbon and more. The EPA selected a total of 21 projects for its first allotment.

The grant is also partnering with the Black Belt Unincorporated Wastewater Program, a nonprofit organization aimed at improving the quality of life for residents and the local environment in the Alabama Black Belt, and seven other institutions.

As part of the project, they will evaluate technology to make sure they use climate-friendly options that will reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They will also compare those technologies against conventional wastewater systems.

“We are very excited about helping these communities with our expertise, with anything that we can offer to address the wastewater challenges,” Bakchan said.

Part of the grant funding will be used to make sure trained professionals maintain the new wastewater systems.

“We want to try to train young people that grow up, live and go to school in these rural regions,” and Kevin White, a retired professor with the University of South Alabama who’s also a grant sub-awardee.

Many of these residents leave because there’s a lack of economic development, White said, partially because there’s no wastewater infrastructure for businesses to tie into.

“These young people leave and go to Montgomery and Birmingham and Mobile and Huntsville to find jobs,” White said.

The grant is part of larger efforts to solve sanitation issues in the Black Belt.

In 2018, the Consortium for Alabama Rural Water and Wastewater Management was formed. The goal was to get community groups, universities, elected officials and industry experts in the same room to talk and plan solutions. White said since 2018, the team has received over $32 million to address water sanitation issues.

Bakchan said this is one of the most important aspects of the current grant.

“We are not starting something from scratch,” she said. “We are building on these community engagement thrusts and activities that have been ongoing for so many years.”

A recent study on statewide wastewater affordability estimated that approximately 445,000 Alabama households — roughly 24% — struggle with affording wastewater access. The consortium is working together to get the money needed to tackle the problem across Central Alabama.

There are three proposed solutions: one is upgrading and expanding the systems of existing municipalities with sewers. Another is identifying clusters of homes that could share a sewage system. The third is addressing onsite wastewater systems for individual homes that can’t be clustered.

“Another part is to try to find appropriate scaled regional management to keep costs low and affordable for all of these residents in the rural Alabama Black Belt,” White said.

This approach could also be a model for other rural places, like the Mississippi Delta region, but Bakchan said none of these proposed solutions matter without community buy-in. A key part of the project is hosting community engagement workshops to give residents input on the technology and solutions they want to see.

“If the community doesn’t want a certain thing, it is not going to happen,” Bakchan said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

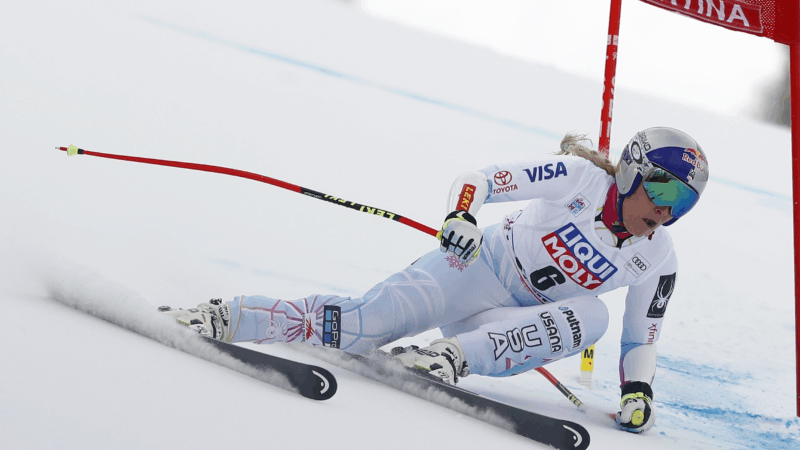

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.

Immigrant whose skull was broken in 8 places during ICE arrest says beating was unprovoked

Alberto Castañeda Mondragón was hospitalized with eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages. Officers claimed he ran into a wall, but medical staff doubted that account.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.