‘A dream come true’: Alabama ‘grandfamilies’ are set to receive opioid settlement funds

Jeff and Donna Standridge enjoy a spaghetti dinner with one of their grandsons at Locust Grove Baptist Church in New Market, Alabama, on August 22, 2024. They came to the meeting to learn more about a new pilot program that gives some opioid settlement money directly to grandparents raising their grandchildren.

Smiles and laughter fill the room at Locust Grove Baptist Church in New Market, Alabama — a small town just outside of Huntsville, in the northern part of the state.

Children run. Chase each other around. Their grandparents, seated nearby, look on. Eat dinner.

They call themselves “grandfamilies.” Everyone here knows each other. They’re all part of a group called Grandparents as Parents. This is one of their quarterly meetings, and they’re excited to get the kids together and catch up.

But lying below the surface, just beneath all the joy in the room, are tough stories.

Donna Standridge is sitting at one of the tables with her husband, Jeff, eating plates of pasta, garlic bread, and homemade chocolate mud pie — a crowd favorite. Between bites, she’s minding one of her grandsons, who is desperate for her attention, hanging onto her arm, calling out Mawmaw, Mawmaw, Mawmaw while she tries to eat and talk.

Standridge is in her mid-fifties, and Jeff is in his mid-sixties. Instead of retiring or traveling, they’re raising their four grandsons.

“My daughter is addicted to drugs,” she says. “Opioids is where it all began. Because of the addiction and being in active addiction, relapsing and stuff when she was clean, it wasn’t a healthy environment for them.”

Standridge and everyone else here came to learn about a new state pilot program. Alabama is set to receive hundreds of millions of dollars from lawsuits with opioid manufacturers. The new program, a partnership with the Alabama Department of Mental Health (ADMH) and the Alabama Department of Senior Services (ADSS), will give $280,000 of that money directly to grandparents raising their grandchildren because their parents struggle with opioid use disorder. The funds, to be administered by ADSS, come from the first round of opioid settlement funds appropriated.

Advocates say it’s not enough to cover the expenses that come with raising a child — much less multiple children — but it’s a good first step.

For the grandparents in the room, any support would be helpful. Standridge says when people think of the opioid epidemic, they often think of the users — of people struggling to overcome their addiction. But it’s the families — especially the children — who have to live with the impacts, too.

“We’re the silent victims, if you will,” she says.

Grandfamilies in Alabama don’t have access to other welfare programs, like the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). This program is supposed to help alleviate that.

The money is set to be distributed to families this fall. Some advocates, like Keith Lowhorne, founder of Grandparents as Parents, are excited. He’s been waiting for this day.

“Oh, this is this is like a dream come true. You’ve got grandparents that are suffering,” Lowhorne said, praising the work done by Alabama’s mental health and senior services agencies. He said this is the first time opioid settlement funds will be given directly to grandparents raising their grandchildren.

“Alabama is not known for being first about anything,” Lowhorne said. “As far as we know, and as far as everyone has told us, this is the first for the country. We are extremely proud of that.”

Other states, like Nevada, will soon be following suit in using settlement money to help grandfamilies. Ali Caliendo, founder and director of Foster Kinship, a statewide support program in Nevada, said using opioid settlement funds to support grandparents and other kinship families is essential for helping keep kids with their families and out of the foster care system.

In Alabama, 48% of foster care entries list parental substance use as the reason for children entering the system, according to the 2021 Alabama Kids Count Databook.

“Every state should be allocating a portion of their settlement dollars to families raising children who are victims,” Caliendo said.

Caliendo said states have an opportunity to use this big pot of money to supplement existing welfare programs — to give more support to grandparents and other kinship families. These grandparents have stepped up, doing the work of raising children, despite their limited resources. And they do it out of love. But love isn’t always enough.

“Love doesn’t buy groceries. Love doesn’t get beds. Love doesn’t solve medical issues,” Caliendo said. “So grandparents really do need extra financial support to make sure that those children can thrive.”

Lowhorne said grandfamilies face difficult and unique challenges. Many of them live below the poverty line and are on fixed incomes. And because they’re older, getting a job can be difficult — or just not an option.

“Some of them are living on $1,500 a month,” Lowhorne said. “And that’s not very much money these days when you’re trying to take care of a kid, possibly a baby. And then sometimes we have problems with preemies because they’re born addicted.”

Lowhorne said many of these children have challenges, too. They may have experienced trauma, abuse or neglect.

Madison County, where New Market is located, is set to receive just over $90,000. Each family that is approved will receive a one-time payment of between $1,000-$2,000. Lowhorne said it’s an amount that is not even close to enough, but it “makes a world of a difference” to these grandfamilies.

They can use the money to buy groceries, pay bills, for dental care or to sign the kids up for sports programs to keep them active. It can also be used to go shopping for school uniforms, as Lowhorne did earlier in the day with his granddaughter he and his wife are raising.

“Let me tell you, I learned some things on how to shop with a young, seven-year-old girl,” Lowhorne said with a laugh. “But it was fun. We had a good time. She said it was a daughter-daddy day.”

While the first round of opioid settlement funds is coming in now, there are hundreds of millions more to come in the next decade. Lowhorne hopes that when the state of Alabama sees how much of a need there is for support, they’ll give more of that money to grandfamilies.

“We want other states to follow because other states are just like Alabama,” Lowhorne said. “You’ve got tens of thousands of grandparents who are raising their grandchildren with hardly any help, if any help at all, like in Alabama — they get nothing.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.

Mitski comes undone

She may be indie rock's queen of precisely rendered emotion, but on Mitski's latest album, Nothing's About to Happen to Me, warped perspectives, questionable motives and possible hauntings abound.

This quiet epic is the top-grossing Japanese live action film of all time

The Oscar-nominated Kokuho tells a compelling story about friendship, the weight of history and the torturous road to becoming a star in Japan's Kabuki theater.

The Live Nation trial could reshape the music industry. Here’s what you need to know

On Tuesday opening statements will begin for the federal antitrust trial against Live Nation, one of the largest entertainment companies in the world.

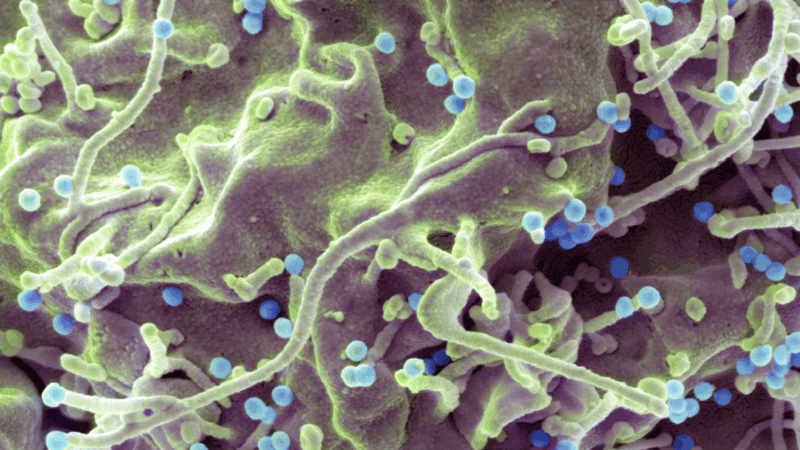

A new one-a-day-pill holds promise for HIV’s ‘forgotten population’

It's designed to take the place of complicated, multiple drug regimens that many people with HIV need to follow. And it's also beneficial because the HIV virus is always evolving.

For filmmaker Chloé Zhao, creative life was never linear

Director Chloé Zhao used meditation, somatic exercises and dance to inspire the cast and crew of this Oscar-nominated story about William Shakespeare's family.

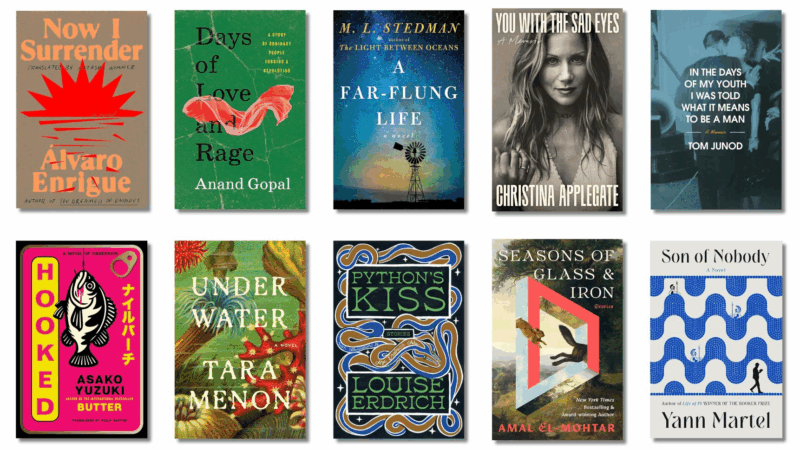

10 new books in March offer mental vacations

March is always a big one for books – this year is no different. We call out a handful of upcoming titles for readers to put on their radars — offering a good alternative to doomscrolling.