To improve birth outcomes for uninsured moms, Birmingham is training more doulas

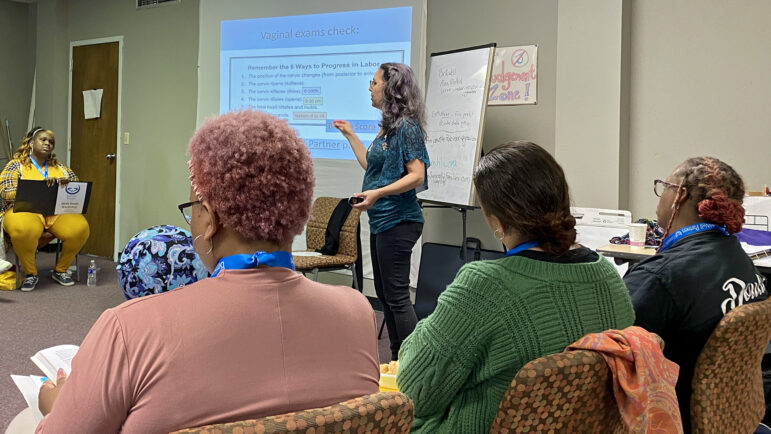

Miracle Barnes (left) acts as a doula for Amanda Rutledge (center) and Sarah Moyer (right) during a BirthWell Partners labor training exercise in Birmingham, Alabama, on April 23, 2023. BirthWell Partners offers training almost monthly, teaching students to become doulas and birth workers.

In a small room of a Birmingham, Alabama church, Amanda Rutledge sits on a floral yoga ball and groans. She’s curled in on herself as she rolls her hips from one side to the other. Her training partner, Sarah Moyer — acting as her baby’s other parent — asks if she can touch Rutledge as she simulates a contraction.

“You my partner, you better be touching me, you done got me pregnant,” Rutledge replies. The two then burst into laughter.

Still, they remain focused yet calm through “labor,” reinforcing consent at each step of the process.

Standing above them is Miracle Barnes, who is acting as their doula — a trained professional who provides emotional and physical support to someone during pregnancy and childbirth. Barnes brushes Rutledge’s hair and encourages her as she labors. Once a timer ends, the women all trade positions.

The exercise is part of a five-day class with BirthWell Partners’ community doula project. It trains people to go into underserved communities in Birmingham — where women don’t have health insurance or can’t afford care — as part of a partnership funded by the city.

In January, BirthWell Partners got a $121,000 grant from the city to sponsor 32 work-study doula trainees and provide free services to 130 families. BirthWell Partners will also use the funds to contract five birth doulas to add to its team.

Co-founder Dalia Abrams said when they created BirthWell Partners in 2011, they set out to reach pregnant people who lack resources. Since then, its doulas have attended nearly 600 births across the state; usually providing services for free.

The non-profit offers its services at reduced or no cost for families who qualify for Medicaid. In 2021, nearly half of all births in Alabama were financed by Medicaid, according to Kaiser Family Foundation.

“They can’t afford to pay $1,500 dollars for a doula to attend their birth, but they’re the people who have the worst outcomes,” Abrams said. “That always needs to be a part of the conversation.”

‘We’re there to support’

Alabama has some of the worst maternal and infant mortality rates in the country, and nearly half of the state lacks adequate access to maternal care. But Abrams said having a doula is only a part of a solution toward improving outcomes.

“Many people do not feel safe in the hospital environment, for a variety of reasons. Racism being one of them. Classism. All the -isms,” Abrams said. “So the bias that each one of us carries is going to impact how someone is treated when they’re in labor, and that makes people feel unsafe.”

BirthWell Partners isn’t the only program in the Gulf South region to implement a community doula project. In 2019, Safer Childbirth Cities launched an initiative in Jackson, Mississippi, aimed at decreasing the rate of C-sections and educating moms on health issues that could lead to riskier, more dangerous births, said program manager Tara Shaw.

The organization, which also has an operation in New Orleans, has only done two doula training sessions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but Shaw said their contract doulas have attended more than 200 births.

While doulas aren’t medically trained, BirthWell Partners’ co-founder Susan Petrus says the emotional support and physical presence of a doula can improve the birthing experience — pointing to research that shows fewer preterm births, fewer low birth weight babies, fewer C-sections and an easier time learning how to breastfeed as a result of their involvement.

“We’re there to support what the client needs outside of their specific medical needs, but that has an impact on medical outcomes,” Petrus said. “When you have that support, it makes a difference.”

‘No shame, no judgment’

Many of BirthWell’s clients have complex needs and birthing plans, and some doula trainees plan to specialize in prenatal and postpartum care. Others focus on creating gender-inclusive spaces to give birth. The training sessions stress autonomy, consent and listening to the birthing person, which Petrus said is the main role of a doula.

“The doula is there for the birthing person,” Petrus said. “They work for the birthing person and there’s a bond of trust that forms. I know what is important to this person for their birth. I’m there to support that and help them to achieve that goal.”

Some trainees are part of a work-study partnership — people who already work with vulnerable groups and are being cross-trained to specifically help pregnant people — like Deneisha Henderson. Henderson works for a maternity benefits company and said that becoming a doula will deepen the ways she can help pregnant people.

“I know that there’s a gap that needs to be filled as a birthing person in the United States, and then myself as being a Black woman hoping to be a birthing person soon,” Henderson said. “Just wanting to be someone to support and help and speak up when they don’t have the knowledge to speak up for themselves — to try to be that person for them.”

Charisse Parker, another work-study trainee, remembers having a doula while delivering her first son more than 20 years ago and the experience stuck with her. She has five children, but her birth experiences were vastly different.

“[With a doula], there were just a lot more options, a lot of flexibility, a lot more freedom that allowed it to be an experience as opposed to, ‘Hey, I’m going to the hospital, I’ll be back soon,’” Parker said.

Parker joined the program to help mothers who have substance use disorders. She’s been in active recovery for almost five years and is a certified recovery support specialist. She said being pregnant deepens stigmas around addiction.

“Having someone like me who’s been through it is not so much looking down at anyone, but giving them hope that, “Hey, I’ve been where you are, no shame, you know. No judgment. I’m here to support you,’” she said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for reproductive health coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.

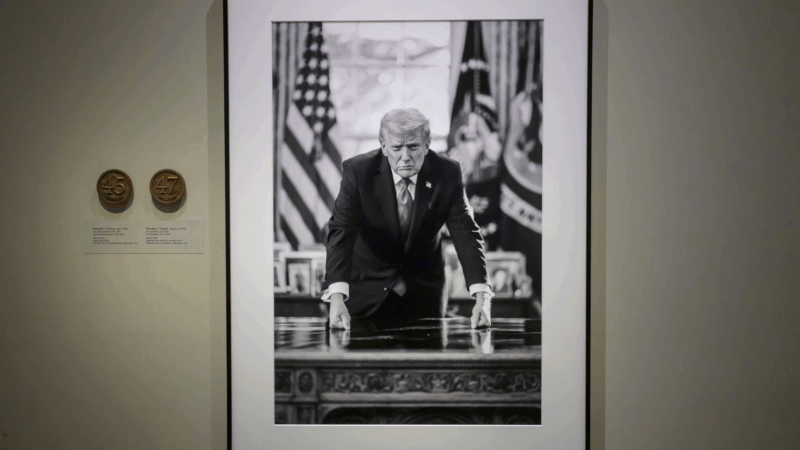

National Portrait Gallery removes impeachment references next to Trump photo

A new portrait of President Trump is on display at the National Portrait Gallery's "America's Presidents" exhibition. Text accompanying the portrait removes references to Trump's impeachments.

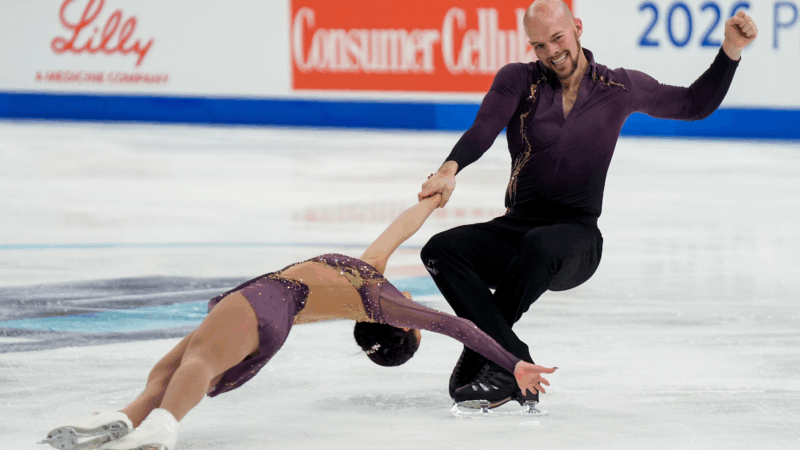

America’s top figure skaters dazzled St. Louis. I left with a new love for the sport.

The U.S. Figure Skating National Championships brought the who's who of the sport to St. Louis. St. Louis Public Radio Visuals Editor Brian Munoz left a new fan of the Olympic sport.

DHS restricts congressional visits to ICE facilities in Minneapolis with new policy

A memo from Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, obtained by NPR, instructs her staff that visits should be requested at least seven days in advance.

Historic upset in English soccer’s FA Cup as Macclesfield beat holders Crystal Palace

The result marks the first time in 117 years that a side from outside the major national leagues has eliminated the reigning FA Cup holders.

Venezuela’s exiles in Chile caught between hope and uncertainty

Initial joy among Venezuela's diaspora in Chile has given way to caution, as questions grow over what Maduro's capture means for the country — and for those who fled it.

Sunday Puzzle: Pet theory

NPR's Sacha Pfeiffer plays the puzzle with KAMW listener Daniel Abramson of Albuquerque, N.M, and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.