LGBTQ doctors are leaving the Gulf South due to discrimination: ‘We weren’t welcome anymore’

(From left to right) Isabel, Tom, Jake, and Connor Kleinmahon stand in the backyard of their New Orleans home on August 18, 2023. The family has since moved to New York because of anti-LGBTQ legislation in the state.

Like most four-year-old kids, Connor Kleinmahon has a lot of toys. But in late August, he only had a few of them out to play with — a toy crane and some building blocks. The rest were packed away in moving boxes stacked along the cream-white walls of his home in Uptown New Orleans, forming a maze on the stained-wood floors. He and his family would be moving to New York the following week, leaving behind friends and neighbors — everything Connor has ever known.

Along with memories and community roots, the Kleinmahons also took valuable medical expertise with them. Connor’s dad, Dr. Jake Kleinmahon, is a pediatric cardiologist specializing in heart transplants for small children. He was one of only three in Louisiana, working for Ochsner Health System since 2018.

But Kleinmahon said that with the increase in anti-LGBTQ policies in Louisiana, he and his husband, Tom, felt it was no longer safe for them to raise young children here. He said the decision to leave was difficult, but it wasn’t hard for his kids to understand. His six-year-old daughter, Isabel, put it in plain terms when he broke the news to them.

“She recognized that we can’t live in a state that’s trying to make laws against our families,” Kleinmahon said. “When you break it down like that, even from a six-year-old, that’s pretty simple.”

Over the last year, state legislatures in the Gulf South saw a deluge of bills aimed at LGBTQ people, especially trans youth. These policies are causing some doctors, like Kleinmahon, to leave a region already experiencing a serious shortage of health care providers.

Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama are all designated as “Health Professional Shortage Areas,” or HPSAs, by KFF, meaning there aren’t enough providers to meet residents’ needs for medical, dental or mental health based on a ratio of the amount of health professionals relative to the state’s population. So, the loss of even one health care professional is especially impactful in the region.

‘They didn’t care about our family’

Tom Kleinmahon said they were watching the Louisiana legislative session earlier this year, and he vividly remembers the moment that he and his husband decided it was time to leave.

“Jake was at work, I was working from home, and we were both watching the Senate Education Committee debate the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ and the pronoun bill,” Tom Kleinmahon said.

When it came time for people to testify against the bill — opponents like medical professionals, teachers, and concerned parents of LGBTQ youth — conservative lawmakers got up and walked out of the chamber. Tom said he couldn’t believe they wouldn’t even listen to the testimony. He and Jake had heard enough.

“It was very clear that they didn’t care. They didn’t care about our family,” Tom Kleinmahon said. “They had an agenda they were going with. And we really weren’t welcome in the state anymore.”

Jake Kleinmahon chimed in, adding, “And to put the icing on the cake, they scheduled this vote during the first day of (LGBTQ) Pride Month. That was no coincidence.”

After discussing it and deciding that it was time to relocate their family, Jake Kleinmahon took to social media to vent his frustrations. He went to his Instagram page — @heartdoctordaddyshark — and posted a photo of himself, Tom, and the kids.

In the caption, he wrote that he had planned to build “one of the highest quality pediatric heart transplant, heart failure, and ventricular assist programs in the country,” and that he and Tom wanted to retire in Louisiana. But after watching state legislatures across the South pass anti-LGBTQ legislation, those dreams had to be deferred.

“We are leaving Louisiana,” Jake Kleinmahon wrote. “Our children come first. We cannot continue to raise them in this environment.”

That post went viral, attracting a lot of attention, both positive and negative. Jake Kleinmahon said that he’s gotten a lot of comments attacking his family’s decision to leave.

“One of the criticisms that I’ve gotten since this has become public is, ‘How could you be leaving these kids in Louisiana who need you?’” he said.

But as he wrote in his post, Kleinmahon said he never wanted to leave. “Louisiana has driven us out. Louisiana has not given back to us.”

LGBTQ doctors rallying support

Kleinmahon’s post also caught the attention of other LGBTQ medical providers in the region, like Dr. Alex Mills.

“Reading Dr. Jake’s post was like looking in a mirror,” Mills said.

Mills was the co-director of the LGBTQ Clinic at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi, which opened in 2019. That clinic has since been shut down after state lawmakers criticized it for providing gender-affirming care to transgender children. Mills echoed Kleinmahon’s frustrations — and his desire to leave a region where he doesn’t feel valued as a provider or as a queer person.

“The motivation to stay here to provide practice and care is dwindling to almost zero,” Mills said. I read that post from Dr. Jacob and was like — totally get it, feel the exact same way. I’m in the exact same boat.”

Mills said that providers like Kleinmahon and himself aren’t outliers. On internal listservs and group messages, other medical providers in the Gulf South are looking for jobs elsewhere and helping each other get out of the region because of the rise in anti-LGBTQ legislation.

“We have been rallying around each other to help,” Mills said. “It’s, ‘Send me your CV. I’ll make sure that it gets on the right desk when that position opens.’”

Mills also said the legislation is also affecting LGBTQ patients, a ripple effect caused by a loss of providers, as LGBTQ patients often turn to providers who identify like them for support.

“One patient interacted with me and sent a message that was saying, ‘I don’t feel safe here anymore. I feel suicidal,’” Mills said. “And that’s just that sentiment of not feeling valued, feeling less than. I’m sure it’s not just one patient who feels that way.”

More data is needed

While Kleinmahon and Mills are individual examples, there have yet to be any formal studies looking into providers choosing to leave the Gulf South because of anti-LGBTQ legislation — making it hard to measure just how many health care providers are leaving.

“Unfortunately, the reality is, despite common collection of a range of demographic factors — race, ethnicity, age, etc. — we are not consistently collecting sexual orientation and gender identity,” said Dr. Sarah MacCarthy, the Magic City LGBTQ Health Studies Endowed Chair at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “So then the question is, what are we hearing anecdotally? And I think there are a lot of differences based on the state that people are in.”

MacCarthy said those individual differences can vary widely. For instance, Alabama has had an injunction in the provision of gender-affirming care, but she’s hearing that a lot of families have stayed and “are watching closely to see what happens.”

“I think it really is what state you’re located in that speaks to your ability to continue to stay there, versus considering crossing state lines or having to fly out of the region altogether to receive affirming care,” MacCarthy said.

MacCarthy also points to the reality that LGBTQ people are not a monolith. Just like any other community, it’s made up of individual people with individual cares and concerns. She said some may see Dr. Jake’s Instagram post and be inspired to leave — to say ‘enough, I’m not going to do this anymore.’ For others, it could be incredibly isolating and sad — a feeling of being left behind.

“And still for others, there could be zero connection between leadership and what they’re doing and how it relates to your day-to-day reality of being on the ground,” MacCarthy said. “I think that there are a lot of different ways that such statements could influence LGBTQ individuals living in these states.”

The Gulf South also isn’t the only region to see families leave as a result of anti-LGBTQ legislation. Stories from states like Kentucky, Florida, and Missouri — all of which have anti-LGBTQ policies on the books — sound eerily familiar to Kleinmahon’s. And while the loss of any family that feels unwelcome is tragic, losing valuable medical expertise is especially impactful.

For researchers like MacCarthy, there needs to be empirical data to definitively prove that anti-LGBTQ policies are driving out medical providers. However, conservative state legislators in the Gulf South have vowed to continue to introduce more bills that target LGBTQ people.

Future studies, if and when they’re conducted, may show what Kleinmahon, Mills, and others are seeing on the ground now: more providers leaving a region that badly needs them because of discriminatory policies.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.

Auburn football player uses NIL funds to open a community hub in Birmingham

Jourdin Crawford, a freshman defensive lineman at Auburn, used earnings from a Name, Image, and Likeness deal to give back to his hometown.

Fear of Iranian mines in the Strait of Hormuz could further slow the flow of oil

Attacks by Iran have already nearly halted the flow of oil through the vital waterway as commercial ship crews fear being hit by missiles, drones or mines.

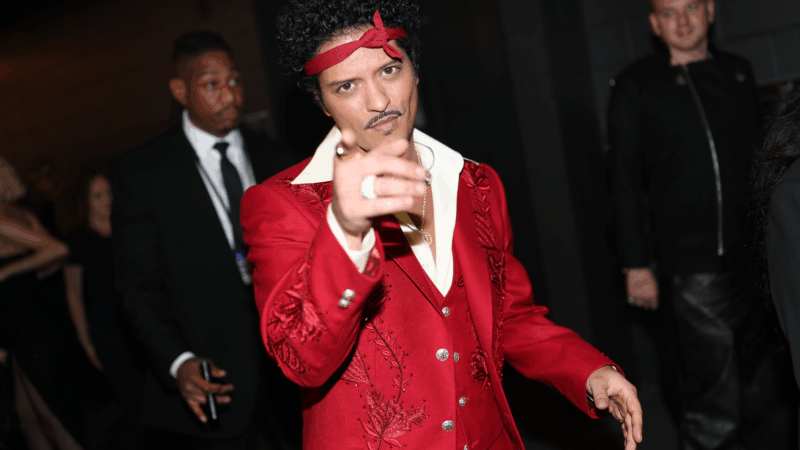

Bruno Mars adds yet another milestone to his career with ‘The Romantic’

Bruno Mars is the most-listened to artist in the world on Spotify. He's won 16 Grammys. In case you thought there were no battles left for him to win, this week he unlocked another achievement.

There’s more than one path to a confessional song

On new albums by viral sensation Yebba and studio whiz Pimmie, it's clear modern R&B has been clearing space for vastly different stripes of singer-songwriter.

Suspect in attack at Michigan synagogue is dead, officials say

Security officers at Temple Israel had "engaged the threat" that apparently started with a vehicle ramming into the building, according to Oakland County Sheriff Mike Bouchard.

This tale of a Chicago school book ban was inspired by true events

Librarian Jarrett Dapier's graphic novel tells a fictionalized account of real-life events in 2013 that restricted access to Marjane Satrapi's memoir Persepolis in Chicago Public Schools.