A pro jiu-jitsu league is bringing grapplers from across the globe to a small city in Alabama

Paul Bahri (top) and Luke Church (bottom) grapple during the fourth day of the Professional Grappling Federation's fifth season at the BComing Church in Decatur, Alabama, on Nov. 2, 2023. PGF is the only professional jiu-jitsu league in the United States, according to founder Brandon Mccaghren.

When you think of jiu-jitsu, the sanctuary of the BComing Church in Decatur, Alabama, may not come to mind.

But for one week in early November, athletes from around the country assembled here to compete in the fifth season of the only jiu-jitsu league in the United States — the Professional Grappling Federation. Jiu-jitsu is a mixed martial arts discipline focused on ground fighting, grappling, and submissions.

The league is the brainchild of Brandon Mccaghren, a black belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu — the most common style seen in competitions — himself.

Decatur is a small, North Alabama city with fewer than 60,000 people. But Mccaghren — a native of nearby Speake, Alabama — saw it as the perfect spot to incubate a growing league dedicated to an MMA discipline that’s experiencing a steady rise in popularity.

Creating PGF

Mccaghren fell in love with jiu-jitsu soon after he started practicing it. He traveled back and forth between Decatur and Los Angeles to train under acclaimed martial artist Eddie Bravo at his gym, 10th Planet, in California. Bravo has a black belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and is a pioneer for his self-developed jiu-jitsu style prominently seen in the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

After years of working with Bravo, Mccaghren became the first instructor of 10th Planet’s satellite gym in Decatur, where he trains countless athletes worldwide. Five years ago, he put his plans for the PGF in motion.

What separates the PGF from other traditional tournaments in the sport is its format. While a typical jiu-jitsu tournament happens over one weekend, the PGF has “seasons” live-streamed on Mccaghren’s YouTube channel. The result is a production similar to other popular sports leagues, complete with announcers and commentators for each match.

“To me, it’s a no-brainer,” Mccaghren said. “We already know what’s palatable. The NFL, the NBA, Major League Baseball — they’re leagues. And so, what I decided we should do is to take jiu-jitsu and just lay it onto a format that we know works already.”

Each season lasts one week, starting with a draft combine to allow the participants to show off their skills. They are then drafted to teams and compete in regular season play, fighting for a spot in the playoffs and a shot at the league championship.

Mccaghren said he realized the ups and downs of an athlete competing over a week-long season instead of a weekend would add depth to the sport and create interesting storylines for viewers to follow.

“The coolest thing to me about the PGF is the way we stretched it out over multiple matches, multiple days where we take a whole week to dig into results,” he said. “It’s not always the ‘top guys’ or ‘best guys’ that make it to the playoffs.”

Another unique part of the PGF is that unlike traditional jiu-jitsu tournaments, where competitors rack up points to win, you can only win a PGF match if you make your opponent tap out during the 6-minute match. That means athletes are forced to grapple to the very last second.

“It doesn’t matter what the points are,” Mccaghren said. “The only way to score points in the PGF is to finish the opponent.”

A diverse group of fighters

PGF has reached a wider audience due to its unique format, Mccaghren’s emphasis on the federation’s media presence, and feedback from his students.

After the second season, Mccaghren implemented a women’s division. This was encouraged by Nekiaya Jackson, PGF’s reigning women’s champion and a 10th Planet grappler.

“He had two seasons and I was like, ‘You need to get some women in here,’” Jackson said. “I compete a bunch, I compete all over and he had never invited a bunch of women in.”

Jackson has been practicing jiu-jitsu for six years and competing professionally for four. The Mississippi native said her path into the sport was unorthodox.

“I moved [to Decatur] for an engineering internship, met Brandon, started training, decided this is what I want to do, and stopped everything else and started training full time,” she said.

Jackson welcomes more women, specifically Black women, to the sport.

“The sport’s growing, it’s something that all people can get into,” she said. “The barrier to entry is pretty low.”

Fedor Nikolov, another athlete in PGF, also left his home to pursue the sport — except his move was intentional.

Nikolov made his way to the U.S. from St. Petersburg, Russia. Nikolov has been training in martial arts since he was 17, beginning with the Russian national martial art of Sambo and then transitioning to jiu-jitsu.

For a long time, people who wanted to compete as MMA fighters, especially grappling specialists, had to have a day job. But Nikolov coming to the U.S. to compete full-time — with no other job — is a sign that the sport is growing.

This past season was Nikolov’s first time competing in PGF, making his way to Decatur from Los Angeles.

“It’s like, for me, the middle of nowhere,” Nikolov said of PGF’s home base.

Big changes on the horizon for PGF

Another sign of that growth? Mccaghren teased some big changes for his league at the end of his latest season.

“We’re going to Vegas,” Mccaghren announced during the finale.

Season six will be held in Las Vegas and Mccaghren says this move would not affect the format of the PGF. The move will allow the league to pay its athletes more. Mccaghren said the new scale will be among the highest paydays in the sport for its competitors. He also hinted that more surprises are on the way, but he’s waiting to reveal them toward the end of December.

But even though PGF is moving out West, Mccaghren does not want to downplay the importance of where the league got its start. He acknowledged it would have been impossible to start PGF in Las Vegas. Many people important to the league’s success — from commentators and photographers to trainers — all hail from Decatur and the league would not have run as smoothly without them.

He also said Decatur gave him a chance to take risks that Las Vegas would not have if the league had started there.

“I think we need to make our mistakes small,” he said. “We have this idea, let’s just start throwing stuff on the wall and see what sticks.”

But Mccaghren isn’t completely going away. He has no intention of leaving his home in “The River City,” and he’ll still run his 10th Planet gym in Decatur.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

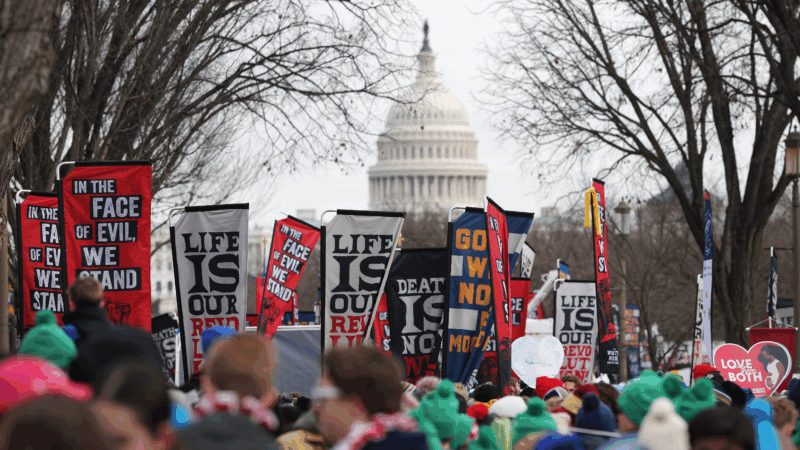

March for Life attendees may have been exposed to measles, DC Health warns

D.C. health officials are contacting people possibly exposed to measles at the March for Life in January, as confirmed cases rise nationwide.

U.S. gave Ukraine and Russia June deadline to reach peace agreement, Zelenskyy says

"The Americans are proposing the parties end the war by the beginning of this summer," Zelenskyy said, speaking to reporters on Friday.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

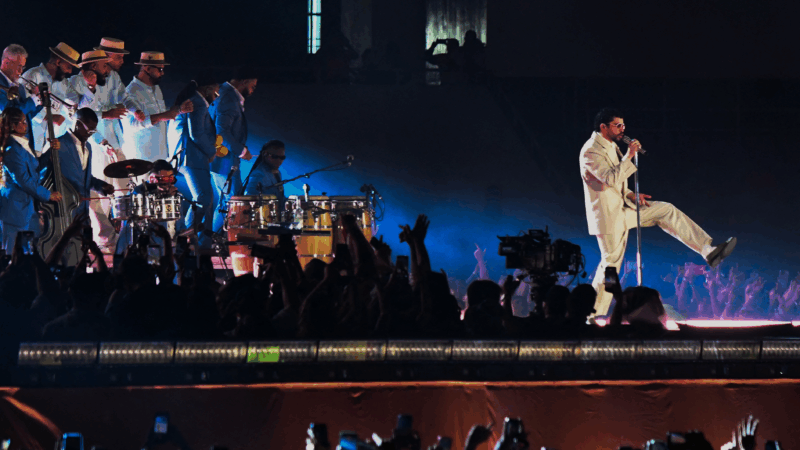

What you should know about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

Will the Puerto Rican superstar bring out any special guests? Will there be controversy? Here's what you should know about what could be the most significant concert of the year.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.