Some teachers and LGBTQ families feel censored by Alabama’s “Don’t Say Gay” law

Abbott Downs has been with her wife for 5 years. They're raising two kids together, including eight-month old Ella.

Matching with Miss America on a dating app and then marrying her sounds like the plot of a rom-com. But it’s reality for Abbott Downs.

“Seven-day free trial match with Miss America. My friends who do online dating all the time were furious with me,” Downs said, laughing.

Downs and her wife have been together for 5 years and are raising two kids — a 12-year-old son from her wife’s previous marriage and an eight-month-old baby girl.

Downs said when they first told her stepson about their relationship, he just took it in stride.

“He was like, ‘Okay, cool. Can we play Xbox?’” Downs said.

But recently a new law in Alabama has been weighing on her family.

In April, Gov. Kay Ivey signed a bill into law that bans discussions about sexuality and gender identity in kindergarten through 5th-grade classrooms.

“As a gay parent raising children, the part that bothers me is it seems to want to exclude conversation about my family, in particular, in the classroom,” Downs said.

During this year’s legislative session, lawmakers considered a bill requiring students to use the bathroom that matched the gender on their birth certificates — a measure that LGBTQ advocates said specifically targets transgender children. The bill’s sponsors said they wanted to protect young girls from predators.

But on the final day of the session, the day Alabama legislators voted on the bill, a last-minute addition to the measure also banned discussions about sexuality and gender identity. It’s very similar to a Florida law critics tagged as the “Don’t Say Gay” law

Downs said she agrees that younger students shouldn’t be learning anything explicit in school.

“Where I think we depart, though, is this notion that somehow talking about my family with two moms is more sexualized and more adult content than talking about another child’s family with a mom and a dad,” Downs said. “I feel like a heterosexual family shouldn’t just be the default.”

“Gay families in Alabama are really actually not anything new,” said Paul Hard, a professor at Auburn University at Montgomery. He’s one of the first people who sued the state for marriage equality in 2013.

While LGBTQ families and relationships haven’t always been visible in the Deep South, they’ve always been here.

“The place of the two aunties and the two uncles that people just ‘nod nod wink wink’ about in Southern culture,” Hard said.

He said that in recent years LGBTQ relationships have started to be openly acknowledged, but this law is a setback.

“We’re communicating to children that their family, that their existence is something shameful,” Hard said. “As long as you can keep people like my husband and I and our kids invisible, we don’t exist.”

According to the Movement Advancement Project, a nationwide policy mapping think-tank, a quarter of LGBTQ adults in Alabama are raising children. Hard says his family considered moving out of Alabama, but it’s home for them.

“There’s a lot of good work our legislators can be doing instead of contributing to this bigotry and making it clear that if you’re LGBTQ we don’t want you in Alabama,” Hard said.

This isn’t the first time Alabama legislation has targeted the LGBTQ community in schools. Until last year, teachers were supposed to follow outdated sex education standards that emphasized that homosexuality is not a “lifestyle” acceptable to the general public and said, inaccurately, that it is illegal under the laws of that state.

Katie Glenn, a policy associate with the Southern Poverty Law Center Action Fund, said the new law is a legislative solution without a problem and makes things more complicated for teachers.

“What this amendment does is it censors our teachers,” Glenn said. “It keeps them from having important age-appropriate conversations, right? And it creates just more red tape, more bureaucracy at a time when teachers are already experiencing some of the most difficult years of their career.”

The law has already had a chilling effect on some teachers who worry about having to out students to their guardians.

Travis Morgan-Chavers teaches elementary education at UAB’s School of Education. He said current standards for elementary education majors put emphasis on social and emotional development and teaching diverse populations and he even teaches a class about the importance of diverse literature for young children.

“There’s a standard for early educators to include that in their classroom and unfortunately, with a bill such as this, it seems that they would have to purge their classroom of such books,” Morgan-Chavers said.

Morgan-Chavers also said that visibility is important in the classroom. He has been with his husband for 10 years and they have a 1-year-old son.

“For us to be visible in the community and to see other people like us that are doing this together, it does provide hope to us individually, to us as parents [and] to me as an educator,” Morgan-Chavers said. “I do think there should be an emphasis on tending to the whole child. As opposed to viewing school as an academic culture or product.”

Dawn Fields teaches third-graders at Huntington Place Elementary in Northport. In her 15 years of teaching, she said she’s always valued student-led discussions in the classroom.

“I’m just trying to be a safe place for a kid who may not have a safe place because of a hundred different circumstances,” Fields said.

She said since she started teaching third graders, topics of gender or sexuality haven’t come up in her class. But that doesn’t mean they won’t. Now if they do, she said it feels like her job is on the line.

“Even though it hasn’t come up, I would almost feel muzzled or handcuffed,” Fields said. “We have students here at this school that have same-sex parents, and what if that kid wants to talk about his moms or her dads?”

Alabama State Superintendent Eric Mackey has said that the law doesn’t just ban discussions about LGBTQ relationships but includes heterosexual relationships as well. It’s not clear how this law will impact classrooms.

Another new law in Alabama requires teachers to tell parents if a student says they might be transgender. Fields said it goes against her philosophy as an educator to not only teach her students but create a sense of community for them.

Fields said if something happens in her class, she’ll follow the proper channels and figure out what to do with administration. But she said her first priority is always going to be the well-being of her students.

Part of her classroom routine is sharing time on the colorful carpet at the front of the room. She encourages students to share whatever they want, but she wonders how that might change with new legislation.

“What if I have a kid next year and he wants to share about his moms? I’m going to let them. They’re eight,” Fields said. “And they’re really not sharing for their classmates. They want to tell me because I’m their teacher. I’m that trusted adult in their safety network. Or that’s what I’m supposed to be, when I’m allowed to be.”

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member reporting on education for WBHM.

The Southern Poverty Law Center is a sponsor of WBHM, but our news and business departments operate independently.

No Nobles Day: Britain’s Parliament boots its last hereditary Lords after 700 years

Government minister Nick Thomas-Symonds said the change put an end to "an archaic and undemocratic principle." The removed aristocrats are 92 of the House of Lords' 800 members.

On her new album, Kacey Musgraves returns home, to the ‘Middle of Nowhere’

Before making her upcoming sixth album, the country star returned to her small-town Texas home and discovered the power of in-between spaces. "I found a lot of clarity there," she says.

How the Iran war is disrupting air travel — and advice if you’re planning a trip

The war in Iran is roiling jet fuel prices and airlines are beginning to hike prices, unsettling travelers far from the Middle East. If you're booking a flight soon, here are things to know.

ChatGPT might give you bad medical advice, studies warn

New research finds AI can point people in the wrong direction. And the quality of health information it imparts depends on how well you prompt the tools.

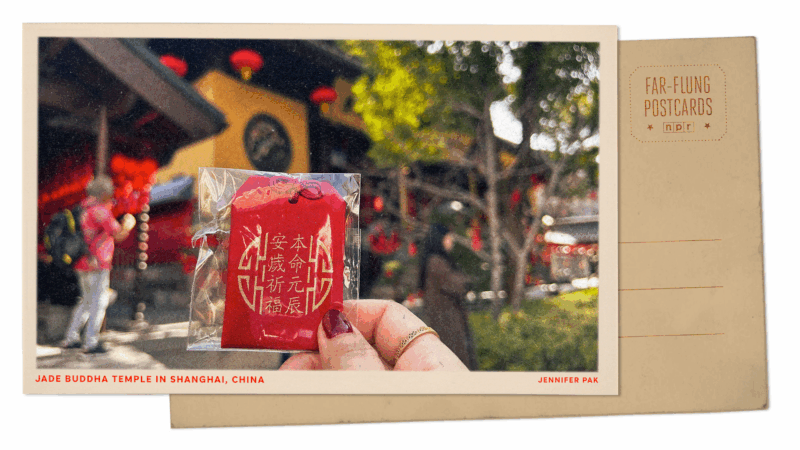

Greetings from a Shanghai temple where you can ward off bad luck in the Year of the Horse

According to Chinese mythology, those born in the Year of the Horse will clash with Tai Sui, a heavenly general. Luckily, there are ways to appease Tai Sui, including amulets at Shanghai's Jade Buddha Temple.

Countries agree to historic release of stockpiled oil to ease the global disruption

Members of the International Energy Agency have announced a coordinated release of 400 million barrels of stockpiled oil in an attempt to counter the disruption in oil trade triggered by the Iran war.