School resource officers turn to mental health to make kids safer

Green Valley Elementary School had its first lockdown drill of the school year on Wednesday, August. 31, 2022.

At the beginning of the school year, Hoover City Schools and the local police department sent a statement about the district’s updated safety protocols to parents. It was in response to concerns that parents had after the mass shooting in May at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

Joshua Flores, a father of a third grader in the district and a preschooler, understood the safety plan couldn’t go into details for security reasons, but he felt it was still vague.

The message from the district did nothing to assuage his anxieties about his kids’ safety. Flores and his family already had a rough start to their summer. His younger son goes to daycare at a Vestavia Hills church where a gunman shot and killed three adults during an evening potluck in June.

“It was really scary. It wasn’t like it was a school shooting necessarily, but it happened in June and everything at Robb Elementary happened in May,” Flores said. “Then to have it hit so close to home.”

He said it’s hard not to feel like a sitting duck — just waiting for something like that to happen at his kids’ schools. He’s also concerned staying hypervigilant will take a toll on students and teachers’ mental health.

“I just feel like this is putting a lot of responsibility, not only on our teachers, but on our kids to police each other,” Flores said. “And I feel really bad that my third grader is going to have to be trained in that.”

All over the country students in K-12 schools practice lockdown drills. Green Valley Elementary School had its first lockdown drill of the school year last week. It was the middle of the day, but it looked like an empty school. When the alarm blared through the hallways and the blue strobe lights flashed, students and teachers knew what to do — lock the doors, turn off the lights, stay quiet and out of sight. Some teachers even stacked naptime cots in front of their doors as barricades.

School resource officers, or SROs, typically oversee lockdown or active shooter drills. Sergeant Brian Foreman with the Hoover Police Department supervises the SRO division in that city. He said SROs care a lot about the students.

“They want to be in that environment,” Foreman said. “They’re not there just to pass time. They’re there to protect the children. And I frequently hear from the SROs that I speak to when they talk about the students. It’s not just the students, it’s my kids.”

He said SROs in Hoover and most of Alabama go by a three-pronged training model that highlights the roles they’re supposed to fill: law enforcement, educators and informal counselors. Foreman said in the last couple of years being that informal counselor has become more important.

“Mental health is a significant issue and a considerable component in a lot of these mass shootings that take place,” Foreman said.

He said SROs’ training includes implicit bias training, de-escalation and mental health awareness. While he said an SRO is in the best position to stop someone who may come to a school with a weapon, he recognizes there’s work before that.

“Our SROs work hand-in-hand with counselors as issues come up and they’re able to form effective partnerships with them,” Foreman said. “And because of that, we’re really able to alleviate a lot of the potential problems.”

School guidance counselors work closely with SROs to report potential threats or issues. Part of their job is also making sure students understand why they have to do lockdown drills.

“As counselors, we are probably on the front line,” said Helena Young, the district counselor for Hoover City Schools.

She said when it comes to safety in schools, counselors are the first people to recognize signs of distress or bullying that could lead to a violent act.

“If we’re involved, we can help students not reach that point of turning towards violence towards others,” Young said. “If a situation happens, I absolutely want my SRO to come in and mitigate the situation immediately. But we would be the ones behind the scenes after providing that mental health support for students who are impacted.”

But Young said a new law in Alabama complicates the situation by requiring counselors to have parental permission to help students with their mental wellness. Young hopes parents will still opt in.

Despite SROs training, some parents aren’t feeling confident in their schools’ safety measures after the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas. .

Mo Canady, the executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, said he understands parents’ concerns.

“If I was looking at that just through a parent’s eyes, and I am a parent and a grandparent, I wouldn’t feel very confident either,” Canady said.

Law enforcement in Texas faced criticism for a slow response to the Uvalde shooting. But Canady said a properly equipped SRO would never wait to stop a gunman.

“Anyone who’s an SRO, who’s not willing to go after an assailant and to stop it through whatever means are necessary, they are in the wrong place,” Canady said.

He said SROs are not placed without thought. It’s a long process of screening and interviews and only officers with years of experience and a passion for education are put in these roles. He also advocates for standardized training across the country and he wants SROs to take advantage of all trainings offered to them.

“I like to see agencies going above and beyond whatever the minimum is,” Canady said. “We don’t want minimally trained officers working in a school environment. We want them to be constantly engaged in training.”

Canady believes there’s always room to improve. He said the biggest goal for his organization right now is to help schools form safety teams where counselors, teachers and SROs work together to prevent shootings from happening in the first place.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member reporting on education for WBHM.

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.

Every business wants your review. What’s with the feedback frenzy?

Customers want to read reviews and businesses need reviews to attract customers. But the constant demand for reviews could be creating a feedback backlash, experts say.

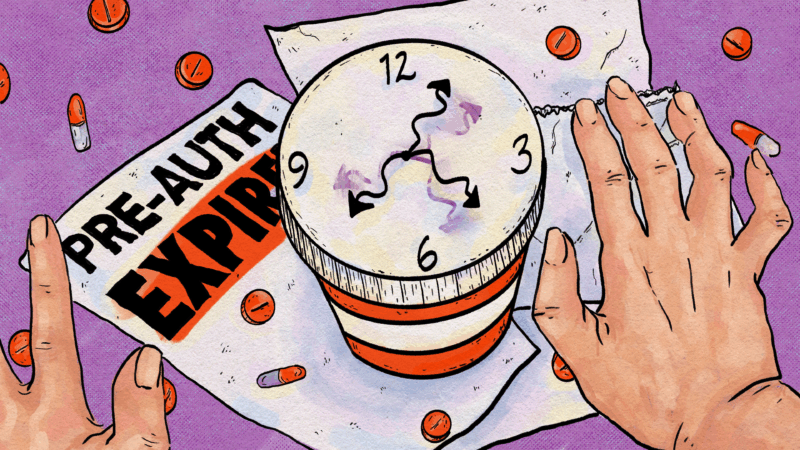

Can’t get a prescription renewed? Here’s how to cope with prior authorizations

These health care hurdles can stand in the way of getting treatment your doctor says you need. Here's what to know about how to deal with them.

‘Get back to integrity’: Oklahoma’s Kevin Stitt on Republicans after Trump

NPR's Steve Inskeep asks Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt about his spat with President Trump, immigration and the future of the Republican Party.

Civil rights leaders say the racial progress Jesse Jackson fought for is under threat

Activists say racial progress won by the Rev. Jesse Jackson is under threat, as a new generation of leaders works to preserve hard-fought civil rights gains.

Tariffs cost American shoppers. They’re unlikely to get that money back

After the Supreme Court declared the emergency tariffs illegal, the refund process will be messy and will go to businesses first.