Food is more than what’s on the plate for this Birmingham urban farmer

Fernando Colunga started working at Jones Valley Teaching Farm as a way to empower kids to have control over what they eat.

This story is part of an occasional series called Extra Credit which shares the stories of non-traditional educators in Birmingham.

In Fernando Colunga’s class, cooking is always the activity of choice. When the 26-year-old instructor announces it’s time to move to the kitchen, all the kids in his class cheer and scramble to get in line at the classroom door.

In the newly renovated kitchen at Jones Valley Teaching Farm, a nonprofit in Birmingham that teaches kids about food and farming, students chop kale and cabbage, saute broccoli and onions, and pour in a savory sauce for a vegetable stir-fry that’s been handmade and homegrown by 10-year-olds.

Colunga said it’s during activities like this one, when the kids get their hands dirty, when they learn the most.

“A lot of the change and a lot of the growth doesn’t necessarily happen when I’m in front of the class teaching about photosynthesis,” Colunga said. “It happens when I’m next to them chopping, when we’re out on the field, harvesting, weeding.”

Known as “Farmer Fern” to his students, Colunga started working at the teaching farm five years ago aftering volunteering for a couple of semesters in college. The time spent growing food and cooking in the kitchen turned into a full-time passion for teaching about the significance of food to young people.

“A lot of them think of food as something just necessary, not necessarily something exciting or something new,” he said. “So when you get to open up the world of food, the world of growing food, the world of cooking your own food to students and seeing that spark in their eye is just incredible.”

“Kids of color are the ones who are impacted the most with food inequality”

He said it’s his mission to introduce kids to all kinds of fruits and vegetables—and not just because he likes cooking, but because he feels his work is helping to address the root cause of systemic issues in access to healthy foods, especially in Birmingham

“Kids of color are the ones who are impacted the most with food inequality,” Colunga said. “So teaching students about food and letting them sort of understand and see where their food comes from allows them to be empowered and take control of health decisions down the road.”

He said having control over your body through the food you eat is the first step in combating systemic issues in food inequality. According to the United States Department of Agriculture about 70% of Birmingham residents live in an area where it’s difficult to get affordable and quality food. Community gardens like Jones Valley help address this issue, but Colunga said it’s not just about how the food is grown. It’s also where it comes from.

“Giving credit where credit is due”

“I’ve been trying to be really intentional about talking about the origin of all of our foods, the origin of our vegetables—where this meal culturally comes from,” Colunga said. “So giving credit where credit is due. So students can see, ‘Wow, like this comes from all over the place. Let me be more open to those cultures.’”

Colunga knows about working across cultures. He was born in Mexico and came to the U.S. as a small child. He said he frequently introduces students to food from his culture.

“All the kids have had veggie tamales, veggie empanadas, veggie tostadas like anything that you can think about,” he said. “All the food that I know is food that my mother has cooked for me. A lot of it is turning scraps into something amazing and beautiful. So that’s where my passion lies with the students is looking at household staples and seeing if we can transform this into a meal that they would love.”

Colunga believes food is tied to everything—community, family and culture. That’s why it’s his number one priority to help students make those connections even if they don’t become professional chefs or farmers. But he said learning about food inspires curiosity and empowers students to think beyond what’s on their plates and give back to their communities.

“We want the students who are coming to our camp or being part of our culinary clubs at the schools to eventually take on our roles, to eventually be the instructors that teach back to their community,” he said.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member reporting on education for WBHM.

Do you know a non-traditional educator in your community worth featuring as part of the series Extra Credit? Email [email protected].

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

‘Hamnet’ star Jessie Buckley looks for the ‘shadowy bits’ of her characters

Buckley has been nominated for a best actress Oscar for her portrayal of William Shakespeare's wife in Hamnet. The film "brought me into this next chapter of my life as a mother," Buckley says.

How, who, and why: NPR flips its famous letters to defend the right to be curious

NPR is standing up for the public's right to ask hard questions in a national campaign dubbed "For your right to be curious." At NPR's headquarters, on billboards in New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., and across social media, NPR's three iconic letters transform into "how," "who," and "why" — a bold declaration of its commitment to fight for Americans' right to ask questions both big and small.

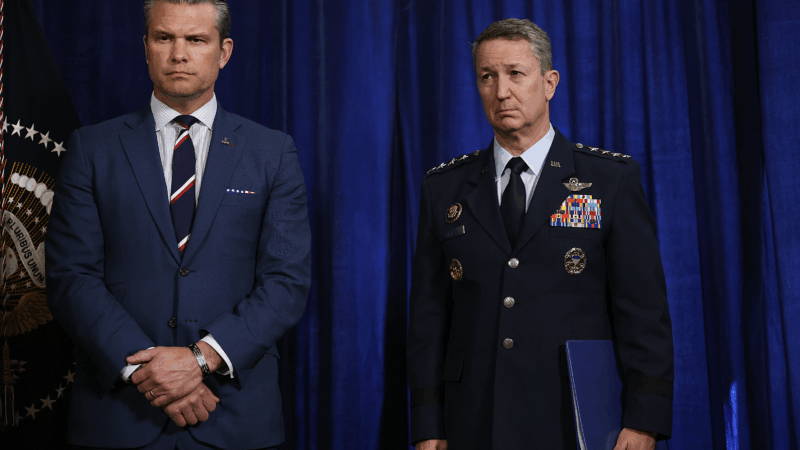

Hegseth: ‘We didn’t start this war but under President Trump we’re finishing it’

The remarks are the first to reporters since the U.S.-Israeli military operations against Iran began Saturday despite weeks of talks designed to stave off a conflict.

Ivermectin is making a post-pandemic comeback, among cancer patients

The anti-parasitic drug became a household name during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is now being embraced as an alternative treatment for cancer. It is as politically polarizing as ever.

Rep. Adam Smith on the U.S. strikes on Iran and the debate over Trump’s war powers

NPR's Leila Fadel asks Democratic Rep. Adam Smith of Washington, the ranking member on the House Armed Services Committee, about President Trump's unilateral authorization to strike Iran.