Will Alabama And Mississippi Expand Medicaid To Low-Income Adults This Time Around?

After a fire destroyed their last apartment in 2019, Kenneth Tyrone King and his family recently saved up enough money to rent a new place in Birmingham, Ala.

But the relief was short-lived. Bills, mostly medical, quickly began piling up at the new address.

“Just various bills in various amounts,” he said. “That $1,600 announcement was yesterday, it was from a collections agency. I was surprised they turned it over so fast.”

For King, 57, this was just the latest development in a cycle of debt. He has not had health insurance for years. He lost his most-recent job at a temp agency after having emergency open heart surgery in December. He barely has enough money for the two prescriptions that he needs each month.

“I can afford one of them, but one of them, it’s like a $60 medication,” King said. “Those types of challenges, if I had affordable health care, or a health care plan, it would have at least covered some of it.”

King falls in the coverage gap. He does not qualify for Medicaid and he cannot afford to buy a private insurance plan. If Alabama expanded Medicaid, that would mean opening up eligibility to people like him and other low-income adults who make up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, which equates to less than $18,000 a year for a single adult.

The Biden Administration is promising hundreds of millions of dollars to conservative-led states that have, for years, refused to open up eligibility to more low-income adults. Many advocates and politicians argue the new incentive is an offer that’s too good to refuse, but it still might not move the needle.

The Hold Out States

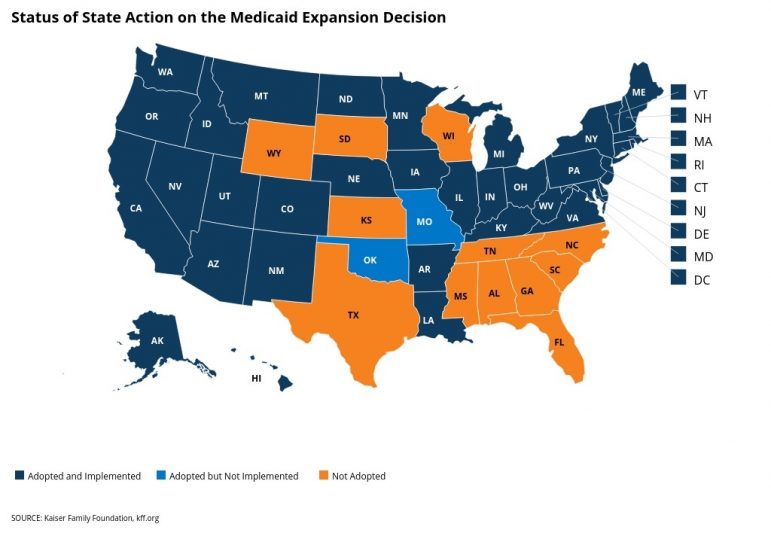

While most states have adopted Medicaid expansion, Alabama and Mississippi are among 12 outliers that have so far refused the move. As it is now, coverage in these states is mostly limited to children, adults with disabilities, low-income seniors and pregnant women.

Estimates show that Medicaid expansion would open up eligibility to more than 550,000 people across Alabama and Mississippi, though that number is from before the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers said it is likely higher now.

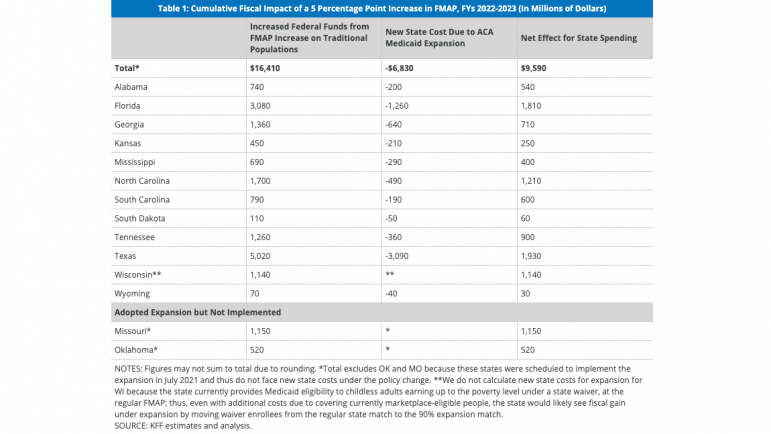

A common argument against expanding Medicaid is that it’s too expensive. States have to pay 10 percent of the cost to cover new enrollees, while the federal government pays 90 percent.

But the new incentive in Biden’s American Rescue Plan is a game changer, according to many supporters of expansion.

“The best deal that we’ve ever been offered, better than any other deal that’s been offered to us on Medicaid expansion,” said Jane Adams, who leads Cover Alabama, a coalition run by Alabama Arise, that advocates for expansion in the state.

With the new incentive, the federal government will chip in 5 percent extra to pay for people who are already enrolled in a state’s Medicaid program. Several studies estimate that the funding boost, which lasts for two years, will more than offset the initial costs of expansion and leave states with hundreds of millions of extra dollars. But it’s not a slam dunk for conservative leaders.

More Than Money

During a press conference earlier this month, a reporter asked Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves about his thoughts on the new deal and whether it would prompt him to reconsider his stance on expansion.

“No sir, it will not,” Reeves replied.

Some in the state hope the governor will change his mind.

“Medicaid expansion is not about putting people on the welfare rolls,” Mississippi Insurance Commissioner Mike Chaney, a Republican, told MPB News. “This is about expanding health care availability to … the poor, the disabled, the folks that fall through the cracks, that are not able to get on the Affordable Care Act.”

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey said she is at least open to discussion. In a statement, she said the state is reviewing the financial details of the deal before weighing in on it.

“I think that would help peoples’ attitude for it, but … it’s just too early to tell,” said state Rep. Steve Clouse (R), chair of Alabama’s Ways and Means General Fund Committee.

According to guidance from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, there is no deadline for a state to expand Medicaid, and the new incentive included in the American Rescue Plan does not expire as long as the law is in effect.

Louisiana’s Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, expanded Medicaid in 2016. A recent study shows that the move has reduced certain hospital costs by more than 30 percent.

“There’s broad support for expansion now,” said Adams with Cover Alabama. “Dynamics have changed. COVID’s changed everything.”

Even in hold out states like Alabama, people across the political spectrum are seeing the benefits. And the pandemic, Adams said, has reinforced the importance of having a robust health care system, while leaving many people without jobs or health insurance.

King, in Birmingham, said Medicaid expansion might give him a chance to get ahead and break the cycle of debt.

“Affordable health care in Alabama would allow me to be more optimistic about making payment plans, because this is something that’s very important to me,” King said. “I want to live long. I’m sure most people do.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WWNO in New Orleans and NPR.

Trump says he is ‘not happy’ with the Iran nuclear talks but indicates he’ll give them more time

U.S. President Donald Trump said Friday he's "not happy" with the latest talks over Iran's nuclear program but indicated he would give negotiators more time to reach a deal to avert another war in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton says he ‘did nothing wrong’ with Epstein as he faced grilling over their relationship

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he "did nothing wrong" in his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and saw no signs of Epstein's sexual abuse as he faced hours of grilling from lawmakers over his connections to the disgraced financier from more than two decades ago.

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.