The Unlikely Spark For Birmingham’s Negro League Reunion

There’s one question Cam Perron has heard over and over again:

“How does a white kid from a suburb of Boston become friends with all of these former Negro League baseball players?”

The answer goes back to his childhood when Perron became obsessed with tracking down Negro League players who had been all but forgotten. That led to him help start an annual players reunion in Birmingham while still a teenager, securing pensions for former players and preserving the history of this slice of American sports.

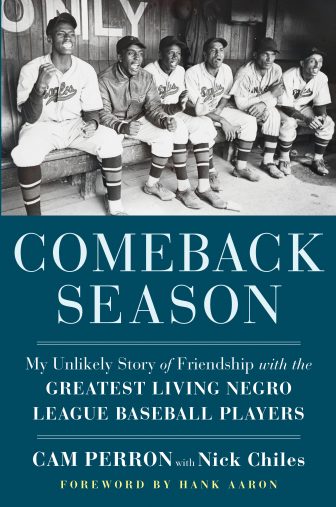

He wrote about his experience in a new book published Tuesday called “Comeback Season: My Unlikely Story of Friendship with the Greatest Living Negro League Baseball Players.”

Perron took an interest in baseball in elementary school. He sought autographs, would write letters to retired players from the 1950s and 60s and met a few Red Sox players at fan events. But his perspective changed when he learned about the Negro League.

“A large part of what happened in the Negro League was not documented and there’s just so much information out there that has yet to be put together,” Perron said. “That’s what really drew me in and over the years allowed me to become such good friends with many of these former players.”

As a 12-year-old, Perron started writing letters to former Negro League players. Within a few months, that developed into phone calls. But the work took sleuthing. Perron looked for clues in old media coverage and other records to figure out where players might be living. He searched the internet for phone numbers. He picked the brains of the players he did locate to find others.

Perron discovered many players did not keep up with their teammates, so he began connecting them over the phone. Then after talking with a fellow baseball researcher, Layton Revel, they came up with a more ambitious idea: a players reunion in Birmingham.

Many retired players were in the South. Revel worked with Birmingham chef Clayton Sherrod, who had been a bat boy with the Birmingham Black Barons in the late 1950s, to organize the event. They knew former players around Birmingham and tasked Perron with inviting those farther away from the city. But there were no formal invitations. Perron simply called players and told them to come. As a naive teenager, he didn’t see a problem with that while Revel and Sherrod were a bit worried given many of these players were older with health issues who would have to travel for hours to get to Birmingham.

“Everyone who said they were going to come came,” Perron said.

According to Perron, about 70 players attended the first reunion in 2010. He was a sophomore in high school. He got permission to skip school for the event.

“They told a lot of their teammates and guys who didn’t make the event, ‘Hey, we had this cool event. I signed autographs for the first time since I stopped playing baseball. You’ve got to come down.’”

It continued annually until last year because of the pandemic, but he said they are discussing plans for another reunion.

Perron’s relationship with dozens of former players grew beyond phone calls and a reunion. In 1997, Major League Baseball agreed to create a pension program for retired Negro League players, but to be eligible, players had to document that they played for at least four years. For some former players, even if they knew about the program, they didn’t have proof of their careers.

Perron searched for anything, including newspaper articles, dated photos or box scores, that could authenticate a player’s time in the league. As of the book’s writing, he and Revel have secured pensions for 48 former players.

More players have died since that first reunion, so there will come a day when no player will be around to receive Perron’s invitation or answer his phone calls. He said that moment will represent a transition from active relationships to preservation.

“[I’ll focus] on the many stories that we were able to capture from the legends while they were still alive [and] utilizing the (Negro Southern League) museum in Birmingham to remember the legacy,” Perron said. “Looking at different ways that you can continue to keep the history even though the players aren’t here.”

Parents, are you sure your kid’s car seat is installed right? Here’s how to know

In this visual guide, certified car seat experts walk through common installation mistakes and how to fix them. Learn what a secure car seat base and a tightly fastened tether look like and more.

Trump announces ‘major combat operations’ in Iran

Israel and the U.S. have launched strikes against Iran, with explosions reported in Tehran and air raid sirens sounding across Israel.

Trump says he is ‘not happy’ with the Iran nuclear talks but indicates he’ll give them more time

U.S. President Donald Trump said Friday he's "not happy" with the latest talks over Iran's nuclear program but indicated he would give negotiators more time to reach a deal to avert another war in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton says he ‘did nothing wrong’ with Epstein as he faced grilling over their relationship

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he "did nothing wrong" in his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and saw no signs of Epstein's sexual abuse as he faced hours of grilling from lawmakers over his connections to the disgraced financier from more than two decades ago.

How the federal government is painting immigrants as criminals on social media

Experts say this kind of media campaign is unprecedented and paints a distorted picture of immigrants and crime

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve