People in Alabama Prisons Confused, Frustrated As State Officials Withhold Their Stimulus Checks

On April 12, a correctional officer escorted Shannon Barlow to a table at the front of Limestone Correctional Facility.

“He had a check laying down, face down,” Barlow said. “I never got to see the front of it.”

The officer told Barlow the check was worth $1,400, his pandemic stimulus payment.

“So I signed the check. He said ‘Thank you, it’ll be posted in 30 days.’ And called the next man in,” Barlow said. “Very simple, short and simple.”

The process turned out to be anything but simple. State officials started holding incarcerated people’s stimulus checks and deducting court-ordered debts, according to multiple interviews and documents reviewed by WBHM.

“I don’t know how they’re actually messing with these people’s money like they are,” Barlow said. “They ain’t never did nothing like this before, and I’ve did almost 30 years in prison.”

Stimulating The Prison Economy

Like many people across the country, Barlow was excited to get his economic impact payment in the mail.

Most incarcerated people don’t earn any income inside prison and rely on family for financial support. People in prison say they need money, not only to buy extra food and soap, but also to pay for necessities like medicine, phone calls and doctor’s appointments.

But soon after Barlow signed his check, officials informed people at the Limestone Correctional Facility that the prison would actually hold all stimulus money for 60 days.

According to a spokesperson with the Alabama Department of Corrections, the 60-day hold is to allow “ample time” for checks to clear and process.

In addition to having to wait for their payments, people in prison were also informed by officials that they might not receive all the money.

Some people, like Barlow, lost all access to their prison bank accounts, known as Prisoner’s Money on Deposit accounts, meaning they couldn’t even access funds deposited by family and friends.

Several incarcerated people said the whole situation has sparked chaos inside prison and has left a lot of people frustrated and confused.

“They’re holding these people’s checks, and Lord knows doing what with them,” said Madeline Peagler, who is at Tutwiler Prison for Women. “Because no one is seeing no court orders for them to take our money.”

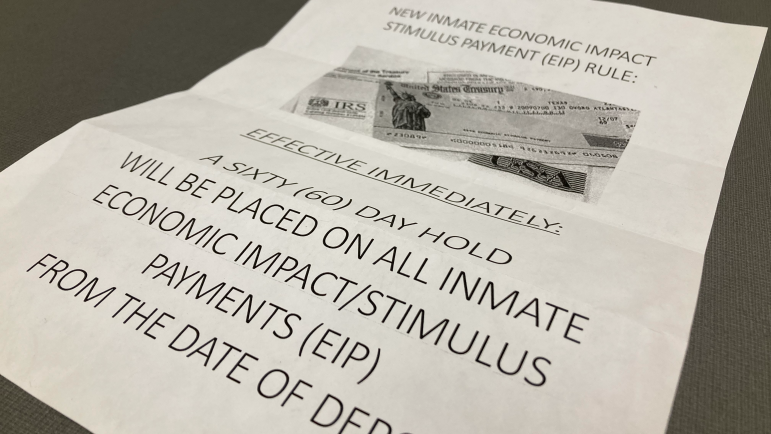

People inside Alabama prisons mailed WBHM copies of announcements regarding the 60-day hold on stimulus payments.

The Cost of Incarceration

What’s happening inside Alabama’s prisons has a lot to do with what’s going on outside, in courthouses across the state.

Mobile County District Attorney Ashley Rich is one of several Alabama prosecutors who have been filing motions to freeze imprisoned people’s stimulus money and use it to pay victim restitution and court fines.

Rich said she believes it’s the right thing to do.

“Why should a criminal defendant who is owed this money to a victim, not have to pay this money out of a stimulus check that was given to them to stimulate the economy?” Rich said. “They’re in prison. They can’t stimulate the economy in prison.”

Some legal advocates, however, are pushing back and question prosecutors’ methods.

“The state is indiscriminately going after the economic impact payments that incarcerated people are entitled to,” said Ellen Degnan, a staff attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Degnan has reviewed hundreds of motions and defended people against them in court in Alabama. She said in some cases, incarcerated people do not receive proper legal notice or a fair hearing.

She said prosecutors are also not considering the specific facts of each case. That’s important, she explained, because some incarcerated people are not required to pay victim restitution until after they’re released from prison, while others only owe legal fees.

“This money is not necessarily going to victims of crime, though that is kind of the public facing rationale for undertaking this debt collection campaign,” Degnan said.

No Protection

Alabama’s imprisoned people are not the only ones losing some of their stimulus money. It’s happening to incarcerated people in other states and people outside of prison with unpaid debts.

Some states have more protections than others. But on a national level, the most recent economic impact payment is not explicitly restricted from garnishment, under the American Rescue Plan.

Yvette Garcia Missri, executive director of the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at the Duke University School of Law, said that this lack of protection brings up bigger questions: Who and what are stimulus payments for?

“We know that with unaffordable fines and fees, that only adds to the racial and economic divide that we already have,” she said. “And we know that people in prison are disproportionately Black and brown, people of color and poor people. And so we’re just making the problem worse.”

It’s unknown how much money has already been garnished from people in Alabama prisons and how much of that will actually go to crime victims.

“The money itself, the purpose of this, was really to help people recover from this pandemic … not to satisfy criminal-legal debt,” Garcia Missri said.

According to officials with the Alabama Department of Corrections, more than 4,500 imprisoned people have received stimulus checks so far. Many are still waiting to see what happens with their money.

At the Limestone facility, Barlow hopes his check posts on his account this Friday, when the 60-day freeze is up. But he’s been told that a few hundred dollars will be deducted. Barlow said he never received a court notice that a motion was filed in his case and he never had a hearing.

If he gets the money back, Barlow plans to add minutes to his phone account and stock up on peanuts and rice.

Editor’s Note: The Southern Poverty Law Center is a sponsor of WBHM, but our news and business departments operate independently.

Parents, are you sure your kid’s car seat is installed right? Here’s how to know

In this visual guide, certified car seat experts walk through common installation mistakes and how to fix them. Learn what a secure car seat base and a tightly fastened tether look like and more.

Trump announces ‘major combat operations’ in Iran

Israel and the U.S. have launched strikes against Iran, with explosions reported in Tehran and air raid sirens sounding across Israel.

Trump says he is ‘not happy’ with the Iran nuclear talks but indicates he’ll give them more time

U.S. President Donald Trump said Friday he's "not happy" with the latest talks over Iran's nuclear program but indicated he would give negotiators more time to reach a deal to avert another war in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton says he ‘did nothing wrong’ with Epstein as he faced grilling over their relationship

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he "did nothing wrong" in his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and saw no signs of Epstein's sexual abuse as he faced hours of grilling from lawmakers over his connections to the disgraced financier from more than two decades ago.

How the federal government is painting immigrants as criminals on social media

Experts say this kind of media campaign is unprecedented and paints a distorted picture of immigrants and crime

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve