What You Can Do About Election Disinformation

Disinformation campaigns have become a given during election season. But this year could be even worse thanks to the coronavirus pandemic.

The virus has sparked changes to Alabama’s elections, from polling locations to absentee ballots, and experts say whenever there’s a disruption to the status quo, there’s an opportunity for disinformation.

“Anytime you have a lot of people seeking out information … there are going to be bad actors trying to supply or meet that demand with a supply of false or misleading information,” said Bret Schafer, media and disinformation fellow at the Alliance for Security Democracy.

Russia’s meddling in the 2016 election opened many people’s eyes to how social media and other platforms could be used to sow confusion and distrust. While foreign countries are still trying to interfere in this year’s election, the threat is changing.

“I’m more concerned about domestic players,” said Schafer.

Americans trying to spread disinformation understand the local context and culture better. They may have specific political goals. Schafer adds there are for-profit companies, mainly in Belarus or the Philippines, that can be hired to run campaigns relatively cheaply.

“The range of threat actors has just expanded exponentially from what we looked at in 2016,” Schafer said. “In 2016, you kind of had to be a nation-state to run a really sophisticated disinformation operation. Now you just need to Google it.”

It happened in Alabama with at least two domestic disinformation campaigns during the 2017 special election for Senate between Sen. Doug Jones and Judge Roy Moore. One used social media to make it appear Moore was receiving support from Russia. Another effort tried to tie Moore to a false campaign to ban alcohol. There’s no indication Jones was involved and he’s decried the tactics.

Schafer said disinformation is a bigger threat to local elections. They’re smaller, so it takes fewer votes to sway the results. For instance, a voter might change his or her choice or not vote at all based on disinformation. A false post online might direct voters to the wrong polling location. Posts containing false or misleading information can narrowly target specific demographics and geographic areas. Plus, fewer eyes are paying close attention to local races.

Experts say one moment to expect disinformation is immediately after the election because of the high number of mail-in and absentee ballots this year.

“It is very likely we won’t have resolution on Election Night,” said Emerson Brooking, a fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. “I think that is when we will be most vulnerable to these efforts to delegitimize the outcome.”

Brooking said there is greater public awareness of disinformation since the 2016 election, but that also spurs a cat-a-mouse game as bad actors turn away from tactics that no longer work. For instance, large armies of automated accounts, called bots, are less common as social media companies have become better at weeding them out.

So what can you do?

First, if you share something online, be sure it is credible and verified.

“When you share a piece of information with friends and family, you are then that source of information,” Bret Shaefer said. “We see foreign and domestic actors try to get real people to pick up misinformation and disinformation without them knowing it.”

But it can be difficult to know what needs verification. One clue is to check in with yourself: be wary of stories that seem to trigger anger, anxiety or other strong emotions.

“Negative emotions can actually motivate [people] to like or share fake news that’s aligned with their political orientation,” University of Alabama journalism professor Jiyoung Lee said.

Similarly, when seeking out information about political candidates or issues, look at multiple credible sources. That can break through narrow views that tend to be reinforced by social media algorithms.

But people can differ on what constitutes a credible source. Official election offices, such as the Alabama secretary of state’s, are one. For news organizations, Lee says reputation is important. They should have a track record of presenting objective, verifiable facts in the reporting. If the subject matter is controversial, the reporting offers more than one perspective. Those same judgements could be applied to individual news stories.

“It can help citizens to get a whole picture of the story,” Jiyoung says.

Finally, Brooking said it’s important to vote. After all, the purpose of election disinformation is to disrupt the democratic process.

“As long as we want an open democratic information space, we’re going to be vulnerable to mis- and disinformation,” Schafer said.

Following Trump’s lead, Alabama seeks to limit environmental regulations

The Alabama Legislature on Tuesday approved legislation backed by business groups that would prevent state agencies from setting restrictions on pollutants and hazardous substances exceeding those set by the federal government. In areas where no federal standard exists, the state could adopt new rules only if there is a “direct causal link” between exposure to harmful emissions and “manifest bodily harm” to humans.

Trump would like the government he leads to pay him billions

President Trump is asking the federal government for billions of dollars in damages, putting his own Justice Department on the spot and creating an unprecedented ethical morass.

Australia bans a citizen with alleged IS links from returning from Syria

The Australian is among a group of 34 women and children who had planned to fly from Damascus to Australia on Monday but were turned back by Syrian authorities to the Roj detention camp due to procedural problems.

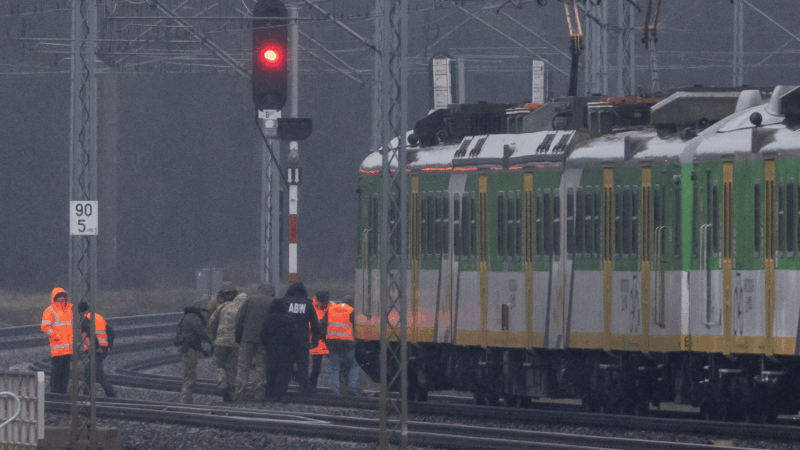

Russia’s hybrid warfare rattles Poland and NATO

Russia is stepping up covert attacks across Europe — rail sabotage, drones, cyber strikes — testing NATO. Polish officials warn "disposable agents" are sowing fear and weaken support for Ukraine.

‘Let them shower in hotels’: Johannesburg Premier faces backlash amid water crisis

In South Africa, as taps run dry in Johannesburg, Africa's richest city, a tone deaf remark by a senior politician there unleashes fury.

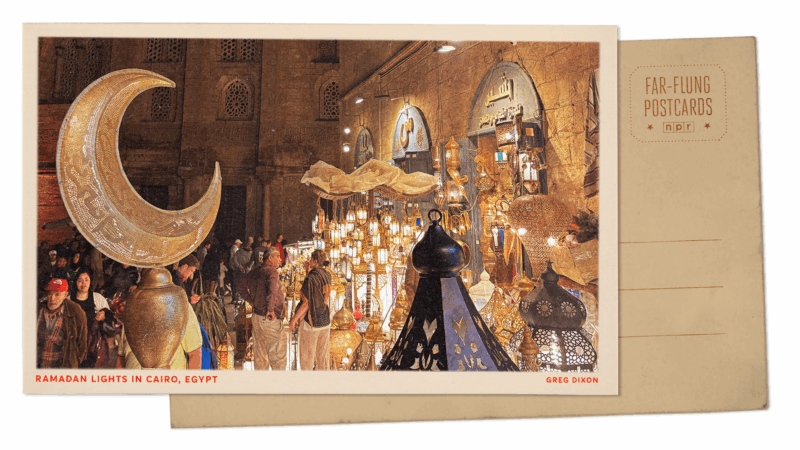

Greetings from Cairo, where lights and decorations transform the city during Ramadan

As Ramadan begins, traditional lanterns called fawanees brighten Cairo. They have become a symbol of Ramadan and are an almost-mandatory home decoration for the holy month in Egypt.