What You Can Do About Election Disinformation

Disinformation campaigns have become a given during election season. But this year could be even worse thanks to the coronavirus pandemic.

The virus has sparked changes to Alabama’s elections, from polling locations to absentee ballots, and experts say whenever there’s a disruption to the status quo, there’s an opportunity for disinformation.

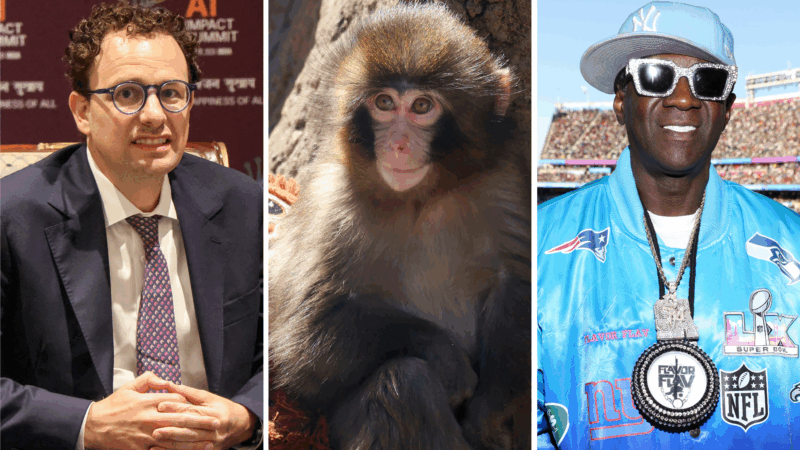

“Anytime you have a lot of people seeking out information … there are going to be bad actors trying to supply or meet that demand with a supply of false or misleading information,” said Bret Schafer, media and disinformation fellow at the Alliance for Security Democracy.

Russia’s meddling in the 2016 election opened many people’s eyes to how social media and other platforms could be used to sow confusion and distrust. While foreign countries are still trying to interfere in this year’s election, the threat is changing.

“I’m more concerned about domestic players,” said Schafer.

Americans trying to spread disinformation understand the local context and culture better. They may have specific political goals. Schafer adds there are for-profit companies, mainly in Belarus or the Philippines, that can be hired to run campaigns relatively cheaply.

“The range of threat actors has just expanded exponentially from what we looked at in 2016,” Schafer said. “In 2016, you kind of had to be a nation-state to run a really sophisticated disinformation operation. Now you just need to Google it.”

It happened in Alabama with at least two domestic disinformation campaigns during the 2017 special election for Senate between Sen. Doug Jones and Judge Roy Moore. One used social media to make it appear Moore was receiving support from Russia. Another effort tried to tie Moore to a false campaign to ban alcohol. There’s no indication Jones was involved and he’s decried the tactics.

Schafer said disinformation is a bigger threat to local elections. They’re smaller, so it takes fewer votes to sway the results. For instance, a voter might change his or her choice or not vote at all based on disinformation. A false post online might direct voters to the wrong polling location. Posts containing false or misleading information can narrowly target specific demographics and geographic areas. Plus, fewer eyes are paying close attention to local races.

Experts say one moment to expect disinformation is immediately after the election because of the high number of mail-in and absentee ballots this year.

“It is very likely we won’t have resolution on Election Night,” said Emerson Brooking, a fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. “I think that is when we will be most vulnerable to these efforts to delegitimize the outcome.”

Brooking said there is greater public awareness of disinformation since the 2016 election, but that also spurs a cat-a-mouse game as bad actors turn away from tactics that no longer work. For instance, large armies of automated accounts, called bots, are less common as social media companies have become better at weeding them out.

So what can you do?

First, if you share something online, be sure it is credible and verified.

“When you share a piece of information with friends and family, you are then that source of information,” Bret Shaefer said. “We see foreign and domestic actors try to get real people to pick up misinformation and disinformation without them knowing it.”

But it can be difficult to know what needs verification. One clue is to check in with yourself: be wary of stories that seem to trigger anger, anxiety or other strong emotions.

“Negative emotions can actually motivate [people] to like or share fake news that’s aligned with their political orientation,” University of Alabama journalism professor Jiyoung Lee said.

Similarly, when seeking out information about political candidates or issues, look at multiple credible sources. That can break through narrow views that tend to be reinforced by social media algorithms.

But people can differ on what constitutes a credible source. Official election offices, such as the Alabama secretary of state’s, are one. For news organizations, Lee says reputation is important. They should have a track record of presenting objective, verifiable facts in the reporting. If the subject matter is controversial, the reporting offers more than one perspective. Those same judgements could be applied to individual news stories.

“It can help citizens to get a whole picture of the story,” Jiyoung says.

Finally, Brooking said it’s important to vote. After all, the purpose of election disinformation is to disrupt the democratic process.

“As long as we want an open democratic information space, we’re going to be vulnerable to mis- and disinformation,” Schafer said.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

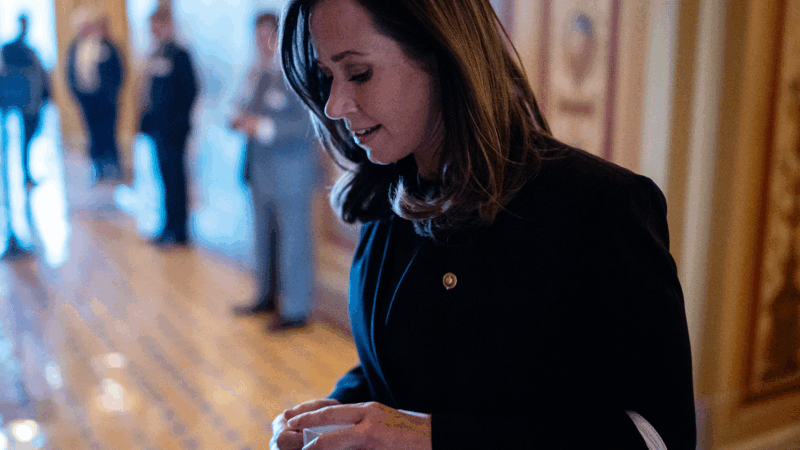

SNL mocked her as a ‘scary mom.’ In the Senate, Katie Britt is an emerging dealmaker

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

Nancy Guthrie case: How do families of missing people cope with the uncertainty?

When a loved one goes missing, relatives can feel guilty simply for eating, says Charlie Shunick, whose sister was kidnapped. Shunick now helps others navigate a nightmare "nobody is prepared for."

This community festival embraces the joys of a frozen lake — while it still has one

As climate change accelerates, local experts say the date Wisconsin's Lake Mendota freezes over is getting later, making safe conditions for activities that rely on snow and ice harder to predict.