Alabama’s Chemical Castration Law Draws Criticism

Some convicted sex offenders in Alabama will soon have to undergo chemical castration in order to get out of prison early on parole. That’s according to a bill signed into law this week by Gov. Kay Ivey.

The term “chemical castration” refers to a treatment that uses hormones such as progesterone to suppress levels of testosterone. Alabama’s legislation applies to individuals convicted of a sex offense involving a child younger than 13. Offenders will have to start taking the medication a month before release on parole and will have to continue taking it until ordered to stop by the courts.

Rep. Steve Hurst, who sponsored the legislation, says the measure is meant to serve one purpose.

“We’re doing this for all the reasons to try to protect children,” Hurst says. “It’s something that’s just, I cannot believe or imagine why someone would harm a small child.”

He says the goal is to prevent child sex offenders from committing future crimes. But Sandy Jung, a forensic psychologist and a member of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, says it’s not a good approach.

“It really is a misguided quick fix kind of formula,” Jung says. “It really does nothing to reduce child sex offending.”

Jung says lowering testosterone levels decreases a man’s libido, but it doesn’t eliminate sexual deviancy or antisocial behavior, which are risk factors for sexually abusing children. And she says not all sex offenders are the same. They respond differently to treatment and need to be individually evaluated by a professional.

“Using something like chemical castration can be useful as what we call an adjunct treatment,” Jung says. “It should not be a stand-alone treatment.”

Chemical castration is allowed in a handful of other states, including California and Florida, as well as some foreign countries. It’s unclear how many sex offenders have undergone chemical castration. A few studies show it can reduce rates of recidivism, but experts warn it should be paired with psychological and behavioral therapy. And there are potential side effects from the treatment, including weight gain, high blood pressure, and depression.

Medical considerations aside, some legal experts say making chemical castration a condition of parole is unconstitutional. Attorney Janice Ballucci directs the Alliance for Constitutional Sex Offense Laws, a nonprofit that advocates for the civil rights of sex offender registrants and their families.

“The way that the Alabama law is written,” Ballucci says, “it really does not provide an individual with a choice, but instead it’s coercive.”

She says the law forces convicted sex offenders to choose between the lesser of two evils – to suppress their sexual identity or stay in prison. Ballucci expects the law to be challenged in court. Officials with the American Civil Liberties Union of Alabama have also spoken out against the legislation. In a statement, they said it presents “serious issues about involuntary medical treatment, informed consent, the right to privacy, and cruel and unusual punishment.”

Under the new law, parolees will have to pay for chemical castration themselves unless they qualify as indigent. The costs are still being worked out, according to Hurst. The Alabama Department of Public Health will be responsible for administering the treatment. If sex offenders stop receiving it, they’ll be sent back to prison.

“And we know one fix don’t cure everybody,” Hurst says. “We know that. So that’s why we’re going to have to continue to monitor it and stay after it and try to make it successful.”

Alabama’s chemical castration law takes effect September 1st.

Photo by quimono

US military airlifts small reactor as Trump pushes to quickly deploy nuclear power

The Pentagon and the Energy Department have airlifted a small nuclear reactor from California to Utah, demonstrating what they say is potential for the U.S. to quickly deploy nuclear power for military and civilian use.

How Nazgul the wolfdog made his run for Winter Olympic glory in Italy

Nazgul isn't talking, but his owners come clean about how he got loose, got famous, and how they feel now

Court clears way for Louisiana law requiring Ten Commandments in classrooms to take effect

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has cleared the way for a Louisiana law requiring displays of the Ten Commandments in public classrooms to take effect.

From cubicles to kitchens: How empty offices are becoming homes

Many U.S. cities have too many office buildings and not enough homes. Developers are now converting some old offices into apartments and condos, but it's going slowly.

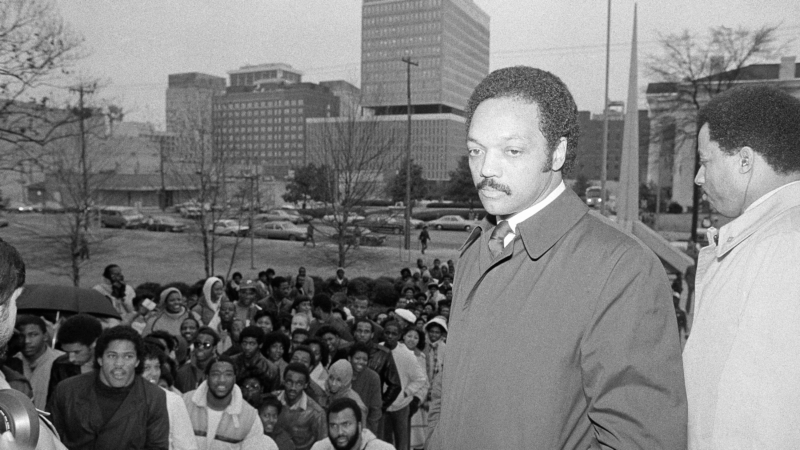

Opinion: The enduring dignity of Jesse Jackson

Rev. Jesse Jackson died this week at age 84. NPR's Scott Simon remembers covering Jackson's 1984 presidential campaign in Mississippi.

A huge study finds a link between cannabis use in teens and psychosis later

Researchers followed more than 400,000 teens until they were adults. It found that those who used marijuana were more likely to develop serious mental illness, as well as depression and anxiety.