In A Segregated County, A New Charter School Offers An Alternative

It’s the first week of class in a new school in Sumter County, Ala., and some fourth-graders are getting to know each other. They have pieces of colored paper they can do anything they want with — the idea is to be creative. Teacher Morri Mordecai cheers them on.

“They put theirs together and said it represented a rainbow,” she says, pointing to one group. “Is that not cool?”

A rainbow is a fitting symbol for University Charter School, where Mordecai works. Of its more than 300 students, only about half are black — and that’s big news in Sumter County, which sits about 120 miles southwest of Birmingham.

More than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education, school integration remains a distant goal in many parts of the country. Enrollment in Sumter County public schools has been virtually 100 percent African-American, and University Charter School aims to change that. For most students, it’s the first time they’ll be learning next to someone of another race.

“We have such a diverse group,” Mordecai says, “and to see them all working together as one, and then talking about it, is just extraordinary. You can’t get experiences like that everywhere.”

After its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the Supreme Court urged school districts to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” But it took years for Alabama to actually desegregate. When it finally did, as in many parts of the country, whites living near blacks avoided integration by moving out of their school zones or starting new private schools.

Ashley Strickland grew up in Sumter. She’s white, and remembers traveling to another county for school. She says she probably would have done the same for her 4-year-old, but now she’s sending her daughter to pre-K at University Charter, a public school operated by the University of West Alabama.

“I’ve got friends with different race children, so she’s grown up that way,” Strickland says. “It doesn’t make a difference to her. It’s important for the kids to co-mingle.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about a third of Sumter County residents live in poverty. And achievement in Sumter’s public schools has been consistently low — the system received a D on the last state report card.

“Sumter County, like so many rural counties in our state, suffers from a lack of highly effective teachers,” says Joyce Stallworth, a retired University of Alabama education professor.

She isn’t convinced a charter school will solve the county’s achievement and integration challenges. Meanwhile, the public schools are floundering.

“Could those resources be used in some kind of fashion to improve the existing public school to make it attractive to white kids and their parents? To black kids and their parents? To all kids and their parents,” she says.

In the first week of school, Morri Mordecai’s students worked on a project: Interview a classmate, then share what they learned with their teacher. One thing a lot of them had in common?

“They were going to miss some of their friends,” Mordecai says. “So the fact that they’re gaining new ones is so awesome.”

It’s by no means clear that this one school will solve Sumter County’s integration problems. But these fourth graders are making new friends — with children they might never have met otherwise.9(MDA2ODEyMDA3MDEyOTUxNTAzNTI4NWJlNw004))

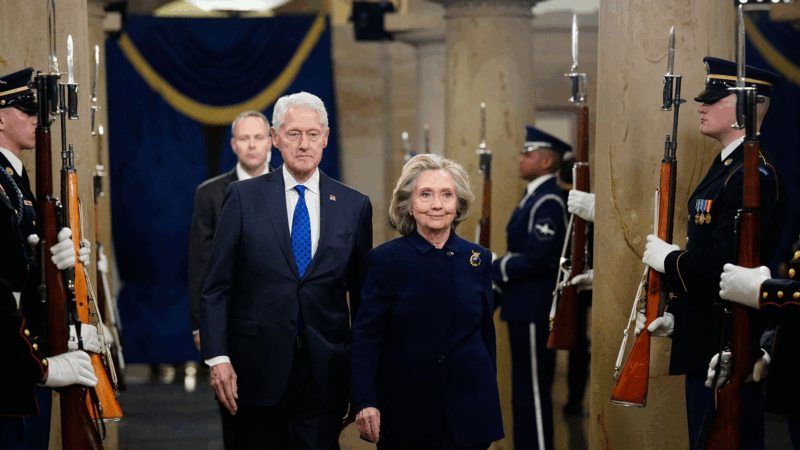

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

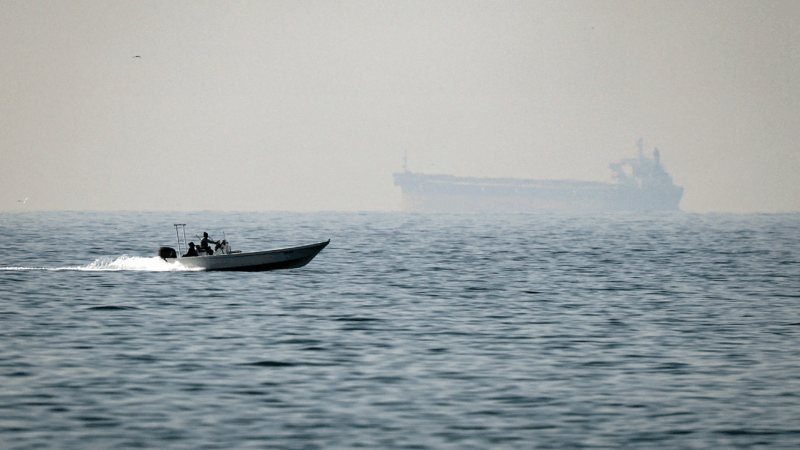

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

‘Hamnet’ star Jessie Buckley looks for the ‘shadowy bits’ of her characters

Buckley has been nominated for a best actress Oscar for her portrayal of William Shakespeare's wife in Hamnet. The film "brought me into this next chapter of my life as a mother," Buckley says.

How, who, and why: NPR flips its famous letters to defend the right to be curious

NPR is standing up for the public's right to ask hard questions in a national campaign dubbed "For your right to be curious." At NPR's headquarters, on billboards in New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., and across social media, NPR's three iconic letters transform into "how," "who," and "why" — a bold declaration of its commitment to fight for Americans' right to ask questions both big and small.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.

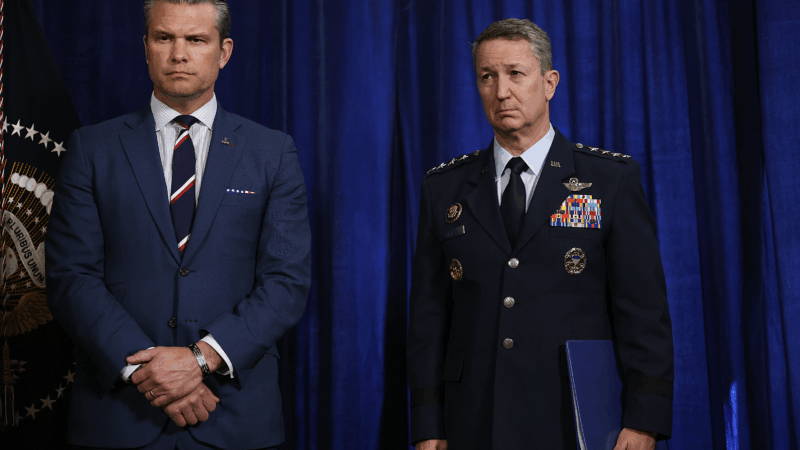

Hegseth: ‘We didn’t start this war but under President Trump we’re finishing it’

The remarks are the first to reporters since the U.S.-Israeli military operations against Iran began Saturday despite weeks of talks designed to stave off a conflict.