Birmingham’s Senior Population Rises While Affordable Housing Remains Limited

By Michelle Little

On a recent Thursday afternoon, residents at Episcopal Place in Birmingham put together puzzles and chatted in the common room. A bell rang signaling lunchtime, and the residents filtered into the community kitchen to pick up boxed lunches of roast beef with rice and gravy.

Episcopal Place is an independent living facility for low-income seniors and adults with disabilities. It opened in 1979. Executive Director Tim Blanton said there was a big demand for affordable housing.

“We started with 100 apartments, and the need was so great that ten years later we added 48 more apartments,” Blanton says.

Rents at Episcopal Place are subsidized by the federal government and can be as low as $300 per month. Just like at some of the ritzier independent living facilities for seniors, residents here can get rides to the store and to doctor appointments. They take computer classes and participate in activities like salsa dancing.

Greater Birmingham’s senior population is rising faster than all other age groups and is expected to double by 2025, according to a recent report by Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham. But federal money for senior housing has been cut in half during the last decade.

Rent at independent living communities in Alabama can be as high as $2,600 a month. With few facilities like Episcopal Place, the demand for affordable and safe senior housing is still high. Episcopal Place resident Thelma Jackson’s primary concern was a safe neighborhood.

Jackson worked for years in downtown Birmingham and lived in West End. She led a successful career teaching homemaking skills at the YMCA.

“The black Y we use to call it – on Eighth Avenue. There was a black Y and a white Y downtown,” Jackson says. “But I worked with the black Y as a teacher – sewing, cooking, homemaking skills.”

After she retired, she was diagnosed with cancer. She moved in with her youngest daughter and eventually went into remission. But by then, her West End neighborhood wasn’t safe anymore.

Jackson says her family had concerns.

“The four children decided that I didn’t need to go back to the house in West End because it had become a different community than when we moved in. People were selling drugs in the house next door to me,” she says.

And Jackson felt secure and welcome when she and her son visited Episcopal Place.

“We came in the door, as we walked in the door, I said Derek ‘This is home.’ He said ‘Momma you haven’t seen anything yet.’ I said ‘I know, this is home – it feels like it,” Jackson says.

But the people at Episcopal Place told her it would be a while. Jackson filled out the forms and waited. Three months later, an apartment opened up. She was lucky. According to Blanton, of Episcopal Place, the typical waiting period is 18 – 24 months.

“We get calls every day,” Blanton says. “People call in, most of the time they need housing. You know something has happened to make them call that they need it now.”

Long waiting lists are a reality at many affordable senior housing facilities across the state and the U.S. There are a few other low-income housing options for seniors in the Birmingham area but some are full and one is closed for renovation.

Many U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development properties were built decades ago when there was more federal money for new developments.

“Those funds continue to flow – they were a lot more robust in the 70s and 80s,” says Adrian Peterson-Fields with the Housing Authority Birmingham District.

Since 2010, federal money for affordable senior housing has dropped significantly. There’s also more competition from private developers. They’re eligible for federal tax credits even if they build pricey independent living facilities.

But Tim Blanton, of Episcopal Place, said there’s still a tremendous need among older adults who don’t have a lot of money to spend on rent. If he had 100 more beds, he said he’s pretty sure he could fill them all in no time.

One note: Episcopal Place is a sponsor of WBHM programming, but the station’s news and business departments operate separately.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

U.S. states take steps to guard against any potential threat from Iran

Iran has made prior attempts to launch terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, but all have been thwarted in recent years. States are bracing for a heightened threat after the war.

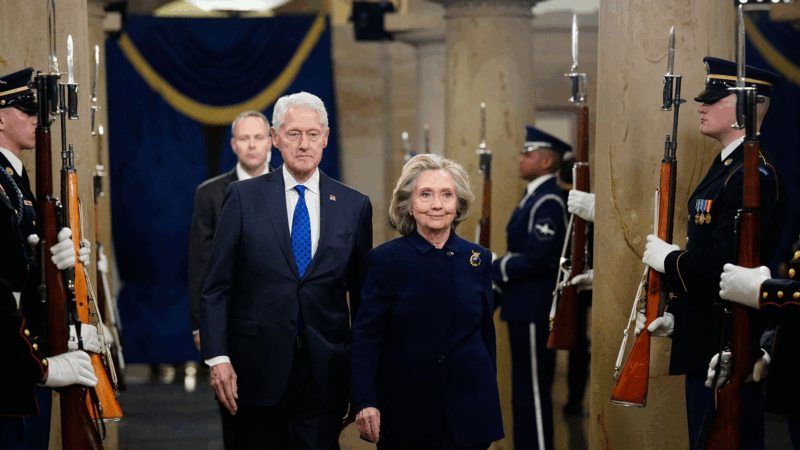

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.