Woodlawn Students Growing a Healthier Neighborhood

Where some see blight and signs of economic decline, others see potential. Under the flight path of Birmingham’s airport and a stone’s throw from busy railroad tracks, almost a dozen Woodlawn High School environmental science students are planting fruit trees. It’s part of a partnership between the school, the Woodlawn Foundation, and The Nature Conservancy that’s transforming vacant lots into lush landscapes to benefit kids and the community.

Junior Jerick Hamilton, who also works at Woodlawn High School’s farm and at Jones Valley Teaching Farm, pretty much does it all.

“Anything from setting up irrigation, to harvesting different crops, to delivering them to teachers,” he says. He discovered his love of growing things back when, as he puts it, his fifth-grade teacher “kind of willed me in.”

That fifth-grade teacher, Scotty Feltman, now teaches environmental science and farming at Woodlawn High School. Today Feltman and his students are planting apples, persimmons, and pears. He says that when kids get their hands dirty and put plants into the ground, they begin noticing the living world around them.

“We don’t always do that. We’re always really occupied with who’s calling us, or the texting … For our students to see that there are a lot of neat things happening around them every day, that’s really rewarding for me.”

It seems to be rewarding for junior Adia Gardner, too.

“It’s fun! And then you get to eat it? It’s awesome!” she says while wielding a shovel, adding, “It’s just good to come out and, like, actually know where your food is coming from.”

Students in this pilot program have already made a woodland park and a meadow for flowers and pollinators. They’ve also made an absorbent “rain garden” to filter water, decrease storm runoff, and reduce bacteria- and mosquito-attracting puddles. The nonprofit Woodlawn Foundation provided the lots, and The Nature Conservancy is leading the project.

Francesca Gross, urban conservation manager at The Nature Conservancy’s Birmingham office, says, “We’re working on growing new conservationists. It’s just a delight to have these kids out here, working in their own neighborhood and seeing how we can transform vacant land into something that’s beautiful and useful, and something they built with their own hands.”

She says it’s vital for the community to buy in, too.

“That’s probably the most important part. It involves a big investment of listening and talking with people about how they feel about their neighborhood,” Gross says. “Does this fit with what they can do, what they care about? That’s critical. One of the biggest mistakes you can make is to think of a project and then go and sort of impose it on a community. Just like the planting itself, this is very much a collaborative process, and I think that’s the key to success.”

That’s true especially with something so new.

“A lot of the kids I work with have never done this before,” she says. “They have never connected an apple tree with an apple. And [now] they’re connecting with nature, getting outside more … We’re just really excited to be a part of that.”

Transforming the lots depends partly on expertise from Gross, Feltman, and landscape architect Jane Reed Ross, who worked with students on the designs. Ross says any community’s physical environment has direct effects on residents’ mental and physical health. That’s one reason the woodland lot has a pedestrian path, the meadow has a tetherball court, and the absorbent rain garden is on a parcel that was prone to unclean puddles. But Ross says she appreciates the process as much as the results.

“They’re developing green thumbs. Kids love gardening — it’s universal,” Ross says. “They embrace it because they recognize that it’s real, and they’re exposed to so much that’s not real. They really get into it.”

Jerick Hamilton and his classmates hope residents will do the same and even bond over the lots.

“If we’re planting and doing things together that are beneficial to all of us,” he says, “I feel like it could bring us closer.”

Besides that possibility, and kids having fun while learning science, conservation, and design, there’s also the lure of sweet, free, local snacks.

“Hopefully my senior year,” says Hamilton, “I’ll be able to try an apple that I planted.”

And he’s not thinking only about himself.

“Anybody can come, and hopefully two years from now, grab a pear or an apple … and see that Woodlawn is growing as a community.”

Seahawks win Super Bowl title, pounding the Patriots 29-13

Seattle's "Dark Side" defense helped Sam Darnold become the first quarterback in the 2018 draft class to win a Super Bowl, to win the franchise's second title.

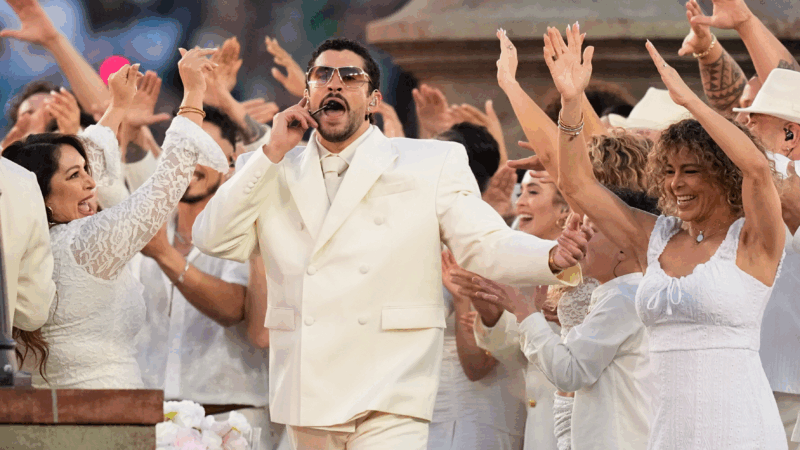

No, that wasn’t Liam Conejo Ramos in Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

A publicist for Bad Bunny confirmed to NPR that the little boy in a blue bunny hat detained by ICE in Minneapolis last month did not participate in the Super Bowl halftime show.

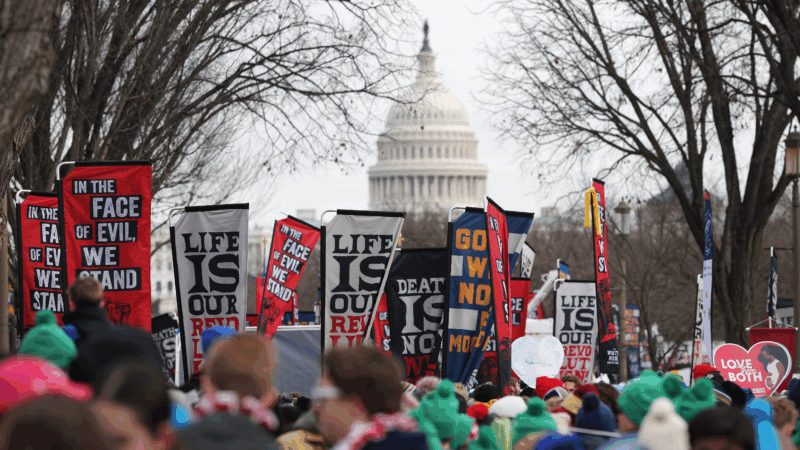

March for Life attendees may have been exposed to measles, DC Health warns

D.C. health officials are contacting people possibly exposed to measles at the March for Life in January, as confirmed cases rise nationwide.

U.S. gave Ukraine and Russia June deadline to reach peace agreement, Zelenskyy says

"The Americans are proposing the parties end the war by the beginning of this summer," Zelenskyy said, speaking to reporters on Friday.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.