Voter ID Law Creates Hurdles for Homebound Man

When Alabama primary voters go to the polls on March 1, they’ll have to show a government-issued photo ID. The law has been in place since 2014 and most people use their driver’s license. But for those who can’t get to a driver’s license office, the law creates difficulties. Samuel Stayer is one voter who ran into problems.

A few years ago, the 72-year-old was diagnosed with cancer and became housebound, spending much of his time in a hospital bed in his Birmingham home. Despite the restrictions, Stayer keeps up on politics.

“I spent a lot of time contacting friends, lawyers, reading, learning about the candidates,” says Stayer.

Stayer is retired from Birmingham Southern College where he was an American History professor. In the 2014 fall election he planned to vote absentee.

“When you return the absentee ballot it says you must include a current photo ID,” says Stayer.

Stayer didn’t have one because his driver’s license had expired and he couldn’t just get out of bed to get a new one. He called the county registrar’s office seeking assurance his vote would be counted.

“She said ‘I cannot guarantee that your vote will be counted,'” says Stayer. “It was extremely frustrating.”

He then contacted Birmingham State Representative Patricia Todd.

“He wanted to vote, but he couldn’t get a photo ID,” says Todd.

Todd contacted Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill. After several phone calls from her and Stayer, Merrill changed Alabama’s absentee ballot application to make it clear physically disabled people can vote absentee. In November 2015, he mailed the new ballot to Stayer along with a letter promising to send a state photographer to homebound voters.

“I think Mr. Stayer has set a great example of what a civic-minded individual needs to do in order to ensure that he or she is involved in the electoral process,” says Merrill.

Despite the extra phone calls and involvement of a state lawmaker, Merrill believes Stayer’s effort to make sure his vote counted was reasonable. Merrill says state law does not make it more difficult for Alabamians to vote.

If he finds one person in the state who is confused about voting, Merrill says he will personally find a way to help.

“It is our desire to ensure that all eligible Alabamians, regardless of their race, creed, color or national origin, have the opportunity to participate in the electoral process,” says Merrill

But Patricia Todd is not convinced Merrill’s attitude reflects state policy. She points to last year’s closure of 31 part-time driver’s license offices, which affected rural areas, some with majority black populations. State leaders said this was necessary due to budget cuts but later reversed the decision after a national outcry.

Todd says voting should be easy but for some Alabama’s ID requirements make it hard for.

“If you’re busy or you’re working late that day or you’ve got kids, it’s a real burden,” says Todd. “I don’t want to say it’s racism. I’m sure in their heart they think they’re doing the right thing, but they never look at the true impact. We’re making it very difficult for people to vote.”

The Secretary of State’s office did send a staffer and an intern to Samuel Stayer’s Birmingham home last November. They brought a camera with them, but it didn’t work. So the intern pulled out his smart phone and took a picture of Stayer, smiling in his hospital bed. Stayer soon received his new ID and can now vote absentee, assured his vote will be counted.

State Representative Patricia Todd is proud of Stayer.

“He’s a real hero for doing what he did,” says Todd.

Other people, Todd says, probably would have given up.

Correction: Story updated 2/25/16 to clarify Secretary of State John Merrill made changes to the absentee ballot and sent staff to Stayer’s home in November 2015. Original story implied this took place in 2014.

US military used laser to take down Border Protection drone, lawmakers say

The U.S. military used a laser to shoot down a Customs and Border Protection drone, members of Congress said Thursday, and the Federal Aviation Administration responded by closing more airspace near El Paso, Texas.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

Pakistan’s defense minister says that there is now ‘open war’ with Afghanistan after latest strikes

Pakistan's defense minister said that his country ran out of "patience" and considers that there is now an "open war" with Afghanistan, after both countries launched strikes following an Afghan cross-border attack.

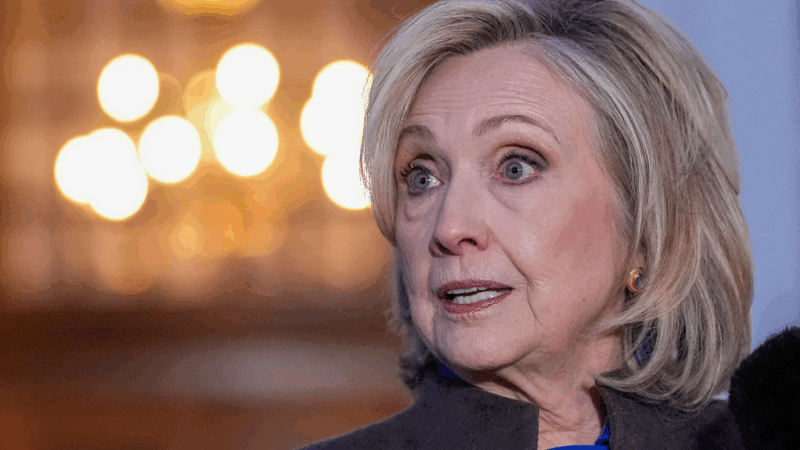

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.