Taking on Tests: Opting Out in Florida

It’s the fifth season of the year in Florida: testing season. Millions of Florida’s public school students, from third grade through 12th, are preparing to take the Florida Standards Assessment. The test has drawn scorn from parents, teachers, school administrators, and even lawmakers—yet it remains the main measure of how schools and districts are graded, kids promoted, and teachers evaluated. Lynn Hatter of WFSU reports about how some parents and children are protesting — choosing a form of civil disobedience by opting out — for the Southern Education Desk series, “Taking on Tests.”

About 20 people showed up for one of the Leon County School District’s Community Conversations. At least a quarter of them were school district officials. Last year, 18 Leon County students opted out of taking the Florida Standards Assessment. That’s a tiny fraction of the more than 20,000 students for whom no data was recorded. There are more than 1.7 million kids in grades 3-10 who take state assessments.

Technically, there’s no such thing as “opting out” of Florida’s standardized tests. State law mandates all public schools students take the exams. The state doesn’t keep track of opt outs. It does use a series of codes to record tests that ended up without a score, and that could be for a range of reasons. One of those, NR2, is used when tests are incomplete, a popular move for opt-outers. The Orlando Sentinel reported there were 20,000 of those exams last year, up from 5,500 in 2014.

It’s a national trend. According to FairTest.org, New York led the nation with more than 22,000 kids refusing exams. Louisiana recorded 5,000 opt out proponents. Orlando’s Cindy Hamilton says despite small numbers overall, the movement is growing.

“We’re here to protest. Protest isn’t supposed to be comfortable. This is civil disobedience. It’s protest. We’re here to fight for something. We’re here to fight against something,” Hamilton says.

But she says many school districts are throwing up firewalls to block kids from trying to escape the exam.

“That’s what’s rolling down from the Department of Ed. And our superintendent, Barbara Jenkins, holds that in her heart,that she must test . And she’s not given direction as Leon County is considering, on how to treat kids who opt out. They have no idea what to do with these kids,” says Meredith Mears, an opt out advocate.

The Opt Out Florida network links local groups. It’s recently published a detailed how-to guide to opting out of the exam. The lengths families will go to protest the exam is intense—from staying home throughout the testing period, to breaking the seal on the exam, but not filling it out. But as Opt Out Leon’s Beth Overholt notes, it’s also not without risks.

“A lot of people opt out by keeping their children at home. Then you run into the truancy issue where it’s the secret handshake …it should be a little more clear,” Overholt says.

Anything the state deems as an excessive absence could end up with a family having to fight it out in court. And because there’s technically no such thing as opting out. parent Kelly Hartsfield says she ran into confusion from teachers her children’s schools.

Leon County School Superintendent Jackie Pons has long derided the way Florida uses standardized tests to grade schools and districts—and more recently, teachers. He’s no fan of the Florida Standards Assessment. Pons says he wants to work with opt out parents to make sure there’s a common message for principals and teachers to handle families that want to opt out. But he admits, he’d prefer they take the test.

“Some of the students who don’t end up testing are some of my best students you know? I know that. That’s sort of a selfish thing I would tell you. I’d like to have them in there. I’d say that. I’m being totally honest with you. But I do understand,” Pons says.

Schools, districts and teachers are judged and rated based largely on those assessments. Students can be promoted or retained based on their performance. Good scores yield more money, so districts have an incentive to test. But it’s that same emphasis on testing that’s frustrated parents. There’s also another effect. The opt out movement in Florida has been largely made up of white, middle and upper class families. And education activist Meredith Mears says she wants to see more low-income and minority families engage in the movement as well. Those kids statistically perform worse.

Still, the movement forges on. Whether it will grow will depend. Since there’s no such thing as opting out, later this spring when test scores come back, education watchers will be counting the number of codes like “NR2 and NT” which could suggest whether a kid opted out of the exam.

This Southern Education Desk series is supported by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

U.S. and Iran to hold a third round of nuclear talks in Geneva

Iran and the United States prepared to meet Thursday in Geneva for nuclear negotiations, as America has gathered a fleet of aircraft and warships to the Middle East to pressure Tehran into a deal.

FIFA’s Infantino confident Mexico can co-host World Cup despite cartel violence

FIFA President Gianni Infantino says he has "complete confidence" in Mexico as a World Cup co-host despite days of cartel violence in the country that has left at least 70 people dead.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

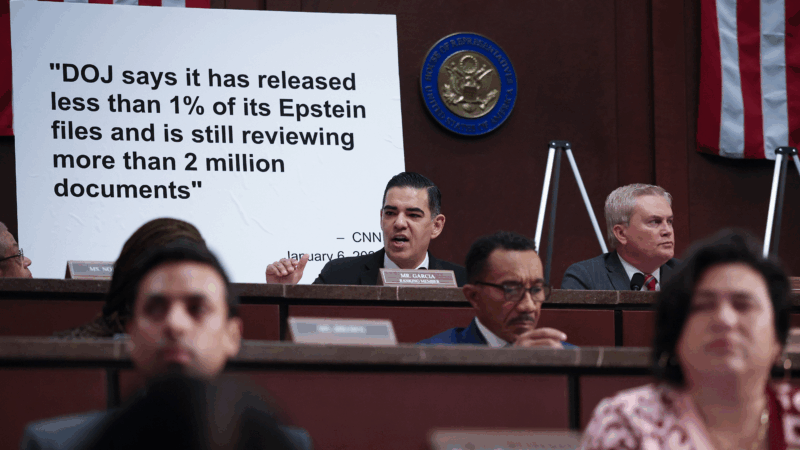

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

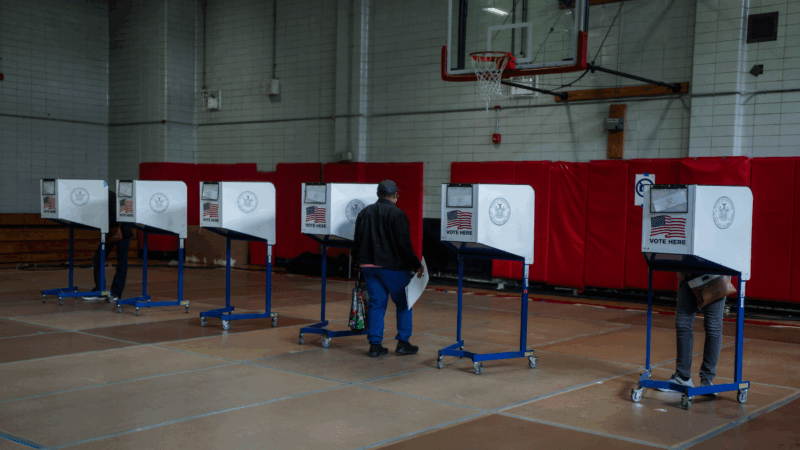

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.