Priming the Pipeline for STEM in the South: Student Incentives in Alabama

Given thousands of related job openings but only hundreds of computer science college graduates, Alabama is trying to ramp up its computer science education. That includes a new policy allowing those classes to count toward core math graduation requirements. WBHM’s Dan Carsen concludes the Southern Education Desk series “Priming the Pipeline for STEM in the South” with a visit to a Birmingham-area class that’s leading the way. Listen above or read below.

Hoover High School junior Griffin Davis is all about his computer science class.

“Honestly, this is probably my favorite part of the day,” he says, “because I get to come in here and I get to be on the cutting edge of things. I get to be … what’s next.”

He’s engineered 3-D-printed parts that’ll help drones drop probes into the Cahaba River, and he’s helped teach programming to grade-schoolers. That’s the type of interest this new class is meant to spark. It’s a more accessible version of an Advanced Placement computer science course — sort of like a science class for non-science majors. It’s meant to be less intimidating than the older, more specialized standard AP course and attract kids from all backgrounds.

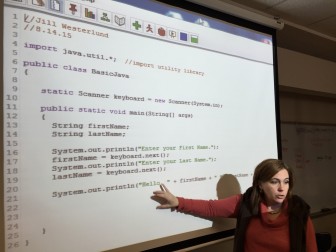

Jill Westerlund teaches both classes — about 40 students altogether. She also writes a computer-science education blog.

“I would love it if every student had a course that incorporated some concepts of technology, whether they’re thinking about innovation, global impact, ethical issues,” she says. “And there’s no way that computer science isn’t a part of everything, whether you’re a mechanic, whether you’re an engineer, whether you’re an accountant.”

The national nonprofit code.org wants to smooth that pathway from class to career. It’s teaming up with educators — not to mention providing funding — to boost the number of computer science teachers in the state from 50 to 100 by next school year.

This year, “comp sci” classes can count toward math graduation requirements.

“That definitely makes sense,” says Davis. “Programming is a whole bunch of data. And you just have to interpret it and then make it easy to use.”

On coding possibly counting as a foreign language in Florida, Davis says, “It definitely is [a foreign language]. The reason I really enjoy programming is … I picked up Spanish really easily; language came easily to me. And I like building things too. I’ve wanted to be an engineer since I was born, basically. So, what programming allows me to do is put those two things together.”

And he says of computer science what foreign-language experts say about their field: “Start it earlier. In elementary school.”

After more than two decades of teaching, Jill Westerlund agrees. As for allowing computer science classes to count toward math graduation requirements, she sees pros and cons.

“A student would be able to take more credits toward their goal in college or the workforce,” she says. “The con, if they’re going to go on to college: do you really want to miss a year of drill-down math on daily basis? Computer science is built on math, but it’s not the same as math homework and math problems every single day.”

But she also thinks the pairing could ultimately increase funding for computer science classes and access for kids across Alabama. The results remain to be seen because the policy and the partnership are so new. What seems certain now, though, is that more kids are getting fired up and engaged in computer science and possibly becoming very employable in the process.

The Southern Education Desk is supported by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. You can access the series and learn more at southerneddesk.org.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

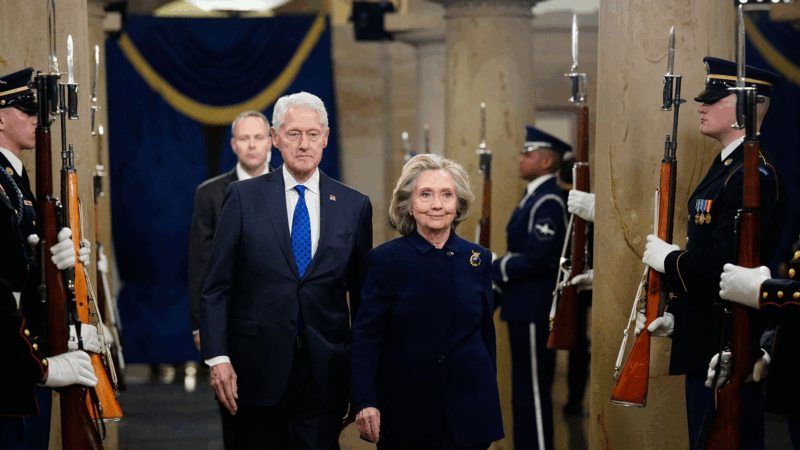

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

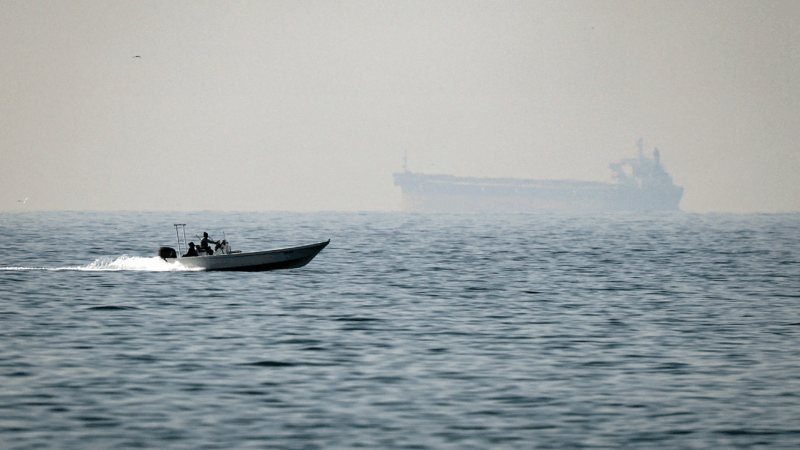

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

‘Hamnet’ star Jessie Buckley looks for the ‘shadowy bits’ of her characters

Buckley has been nominated for a best actress Oscar for her portrayal of William Shakespeare's wife in Hamnet. The film "brought me into this next chapter of my life as a mother," Buckley says.

How, who, and why: NPR flips its famous letters to defend the right to be curious

NPR is standing up for the public's right to ask hard questions in a national campaign dubbed "For your right to be curious." At NPR's headquarters, on billboards in New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., and across social media, NPR's three iconic letters transform into "how," "who," and "why" — a bold declaration of its commitment to fight for Americans' right to ask questions both big and small.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.