Alabama Cattle Ranchers Hit Hard by Drought

It’s breeding season at Cow Creek Ranch in Aliceville, AL.

Owner Joy Reznicek and some of her ranch hands are preparing to artificially inseminate a few dozen cows.

They move one particularly stubborn cow into the squeeze machine — which gently hugs the cow so she can’t move. That’s when Brice Allsup gets to work. He slides on an arm-length plastic glove, takes a long, slender tube filled with all the ingredients needed to make a baby cow and inseminates the animal. It’s not glamorous, but Allsup’s a pro with more four decades of experience.

“I tell people I get up to my armpits in my work and I can take a lot of crap,” Allsup says.

He won’t know for five months whether the cow is pregnant. The long wait will feel even longer if it doesn’t rain in Alabama.

After months of warm, dry weather, it did finally rain this week. But a few days of precipitation won’t erase months of drought. The lack of rainfall has crippled the state’s $2 billion cattle industry. The drought has forced ranchers to buy hay from out-of-state and if the dry weather persists this winter, things could get a lot worse for farmers and their herds.

Cows eat lots of grass. But grass doesn’t grow without water. Most of the pastures on Joy Reznicek’s 2,400-acres are yellow and dusty. Her ranch looks more like the parched Nevada desert than the rich grasslands of western Alabama.

“It’s very abnormal,” she says. “We would typically see a lot of mud around here this time of year. So, we are abnormally dry.”

Most of Pickens County is under extreme drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Before this week’s rain, it had been months since the area had seen any precipitation.

No rain means no grass for her cows to feed on. Reznicek has needed to tap into her hay reserves. Normally they wouldn’t need to do that until almost February, says ranch manager Jeff Reznicek, and they’re not sure how long their stockpile can last.

“And a lot of that depends on whether or not we get some moisture come January of February,” he says. “If that happens, we’ll get a little growth out of our grass, the days will start getting longer and we’ll get some growth. But if that doesn’t happen, we could be putting hay out until the first of April or something like and we don’t want to get into that situation.”

Creeks and ponds are drying up all over Alabama. So, not only are ranchers having to buy hay but water too. Ranchers that can’t afford to do this are forced to sell off portions of their herds and the money they get from selling their cattle is dropping. Last year, a calf fetched about $1000, this year only half that.

So, Reznicek is determined to breed as many cows as possible. But it could be in vain. A lack of water and food can send cows into survival mode. When this happens to pregnant cows, those expectant mothers often abort their calves.

“It begins shedding those unnecessary things to survive,” she says. “A pregnancy is not a necessary thing for that [cow] to survive, in fact, it’s taking nutrients away from that cow. So, it’s kind of the evolution of that cow surviving.”

But it’s not all bad news for Alabama ranchers. Forecasters predict this winter will be warmer and not as wet as normal. That’s good for cows because their hair is a poor insulator.

When they’re cold and wet, cows burn more energy and need to eat more. Warmer weather means less stress on cows and Reznicek hopes that will make her hay supply last a little longer.

Chilean Smiljan Radić Clarke wins architecture’s highest honor

The Pritzker Prize was awarded Thursday. "In every work, he is able to answer with radical originality, making the unobvious obvious," said fellow Chilean architect and prize chair Alejandro Aravena.

El Niño is set to take hold this summer, driving up global temperatures

A potentially strong El Niño weather pattern will likely emerge this summer and persist through the rest of the year. The hottest years on record generally occur in years when El Niño is active.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

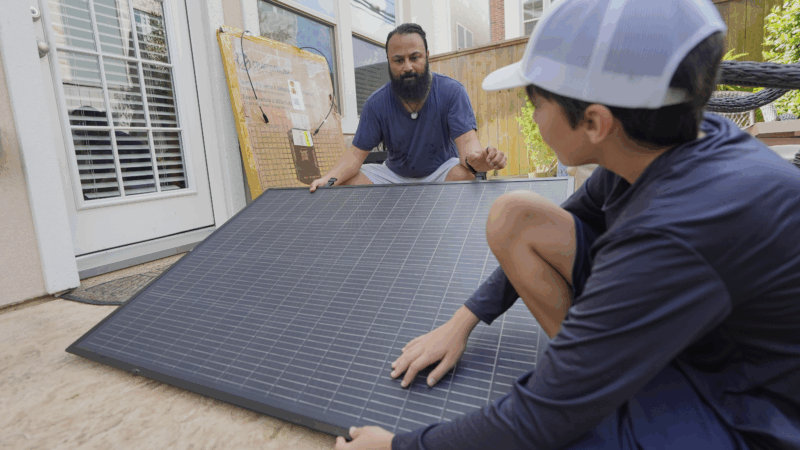

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

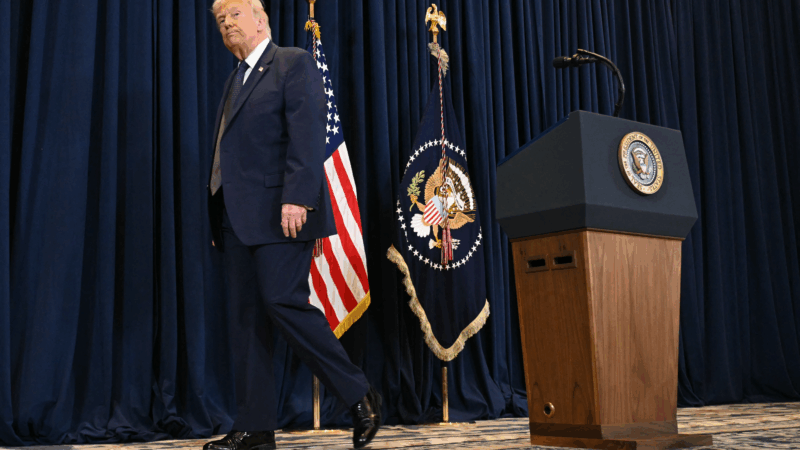

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.