A Day in the Life of a Birmingham Walking Beat Cop

Officer B. Steward of the Birmingham Police Department is a walking beat cop. Walking beats are part of the Violence Reduction Initiative, an effort to reduce crime in the city.

Homicide rates are on the rise across the country. In Birmingham, the city finished 2015 with a dramatic 55 percent increase. In response, law enforcement is stepping up efforts to combat violent crime. One key element: adding more face-to-face engagement between police and the community through old fashion walking beats.

Officer B. Steward from the Birmingham Police Department has been a cop for about a year. He has been a walking beat cop since the city implemented the Violence Reduction Initiative (VRI) last year. The VRI is an effort by city law enforcement officials to lower crime. Most of these patrols take place in West Birmingham, where police officials say most violent crimes occur.

Steward is a utility officer, meaning he doesn’t have a set beat. He patrols different neighborhoods almost everyday and he likes it. The change gives him opportunities to meet people in neighborhoods all over west Birmingham, he says. Today he’s in Powderly.

Steward is white and the beat he’s working is in a predominantly black neighborhood, but the distinction has never been an issue for him, he says. He drives slowly up and down streets, smiling and waving at every person he sees. And they all wave back. He describes it as public relations.

Steward also gets out of the car to walk around and talk to people.

He meets Curtis Sumpter, a retired ironworker. Sumpter and a few of his friends are enjoying a leisurely afternoon.

“I’m glad to see y’all coming. I’m glad to see y’all period around here,” Sumpter says joyfully.

Sumpter and his friends were skeptical at first. They usually see cops only when something bad has happened, Sumpter says. Their first thought when they saw Officer Steward was why would a cop wave, then stop the car and approach them? The group relaxes when Steward explains he’s just stopping by to say hello. Resident Antwan Sanders says this interaction could make people feel more at ease when they see a police officer.

“You gotta make them [people] feel comfortable. If the police make the people feel comfortable and tell them, ’Hey! Hey! I just came out here to talk to y’all,’” says Sanders. If more cops talk to people on their beats it might help build trust between the two, he says.

Foot patrols are popping up all over the country. Cities from Boston to St. Louis have added or increased walking beat cops, who spend their shifts smiling, waving and talking to people. Steward says, depending on the number of calls he gets in a day, that’s pretty much his life. The life of a walking beat cop in Birmingham. He says it’s changed him.

“You actually get to learn a lot more about what’s going on around the beats you’re working,” says Steward. “A lot of times people are thanking you for what you do.”

Steward says not only has this program helped him get to know the community, but it’s also helped show the people in the community that cops are human and even approachable. That’s what police leaders are going for according to Captain Scott Praytor with the Birmingham Police Department. He says face-to-face interaction is paramount to building stronger relationships between the police force and the communities they serve.

“We need to learn to talk to one another again and to communicate,” Praytor says. “In this age it’s hard to do, with all the social media, to actually look somebody in the eye and talk to them again, to be able to have a conversation. And we’ve got to get back to being able to do that.”

Those relationships can lead to community tips that stop crime in its tracks, Praytor says. And many West Birmingham residents agree. Walladean B. Streeter is the President of the Bush Hills Neighborhood Association.

“I hear so many times at meetings when they [residents] say, they report something to you,” Streeter says. “And I say, well have you called the police? ‘I don’t wanna get involved.’ But they want you to get involved.”

When people get to know the police officers that patrol their neighborhoods, they’re more likely to say something to law enforcement when they see a crime, Streeter says. She adds this can only lead to safer communities.

Viral global TikToks: A twist on soccer, Tanzania’s Charlie Chaplin, hope in Gaza

TikToks are everywhere (well, except countries like Australia and India, where they've been banned.) We talk to the creators of some of the year's most popular reels from the Global South.

Memory loss: As AI gobbles up chips, prices for devices may rise

Demand for memory chips currently exceeds supply and there's very little chance of that changing any time soon. More chips for AI means less available for other products such as computers and phones and that could drive up those prices too.

Brigitte Bardot, sex goddess of cinema, has died

Legendary screen siren and animal rights activist Brigitte Bardot has died at age 91. The alluring former model starred in numerous movies, often playing the highly sexualized love interest.

For Ukrainians, a nuclear missile museum is a bitter reminder of what the country gave up

The Museum of Strategic Missile Forces tells the story of how Ukraine dismantled its nuclear weapons arsenal after independence in 1991. Today many Ukrainians believe that decision to give up nukes was a mistake.

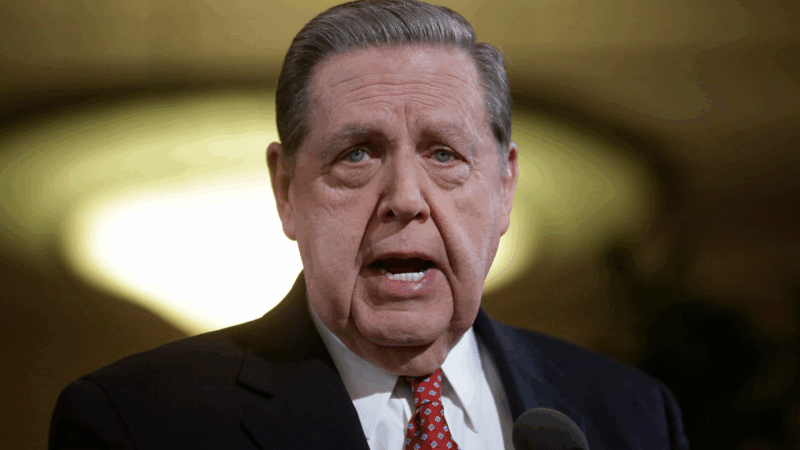

Jeffrey R. Holland, next in line to lead Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, dies at 85

Jeffrey R. Holland led the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, a key governing body. He was next in line to become the church's president.

Winter storm brings heavy snow and ice to busy holiday travel weekend

A powerful winter storm is impacting parts of the U.S. with major snowfall, ice, and below zero wind chills. The conditions are disrupting holiday travel and could last through next week.