In Football Country, Concussions Spark A Parental Dilemma

More and more people are learning about the risks contact sports pose to the brain. So even here in football-loving Alabama, parents and young athletes are wrestling with a serious dilemma, one that could affect them decades later: to play or not to play. To help parents facing that decision, WBHM’s Dan Carsen got some personal perspective from families who’ve already faced sports-related concussions. Listen above or read below.

Here’s something no parent wants to hear:

“It was like, a one-on-one blocking drill. I don’t know if I like put my head down or something, but we just hit heads. Really hard. And I was just like dazed I guess. My head started hurting, and like, everybody said I looked like dizzy and stuff. It hurt pretty bad. I don’t really remember it.”

That’s what happened to Will Tuggle of Vestavia Hills during a middle-school football practice. The rising junior is six-foot-three now, but he was even bigger compared to his peers back then, and it didn’t matter. And the worry didn’t disappear after the day of that hit.

“There’s not a whole lot you can do,” says Will’s mother, Vicki Tuggle. She says she felt helpless because “they can’t tell you how long the symptoms are going to last, or exactly what the treatment is — there’s not really a treatment. You just have to pretty much deal with the symptoms as they come. There aren’t a whole lot of options.”

Concussions are “clinically diagnosed,” meaning there’s no, say, blood test or scan that definitively shows their presence. And they vary widely in severity and symptoms. Will had headaches and dizziness for weeks. Vicki ended up doing research on her own and connecting with parents who were in the same boat. And it turns out there were plenty of them.

“A bunch of my friends got concussions also. We had a lot of people injured that year,” says Will, before his mom chimes in: “Yeah, at one time toward the end of the season, somewhere between seven and 10. They still wanted to be part of the team, although they couldn’t play. So they would wear their jerseys and stand or sit on the sideline. And there was a lot of talk that, ‘really? That many kids are out with concussions?'”

That eighth-grade year was the last time Will and some of his friends played football.

“I think it weighed into a lot of our decisions,” says Vicki. “I would say a few of them are still playing, but I think most of them have found other sports. They’ve gotten out of the football business. Another friend of his that suffered one decided to play [again] freshman year and ended up getting another concussion. So we felt confirmed that we made the right decision.”

But she says that, without that 20-20 hindsight, especially here in football-loving Alabama, it’s not an easy decision. Anne Giraud agrees. She has two sons who’ve suffered a total of three concussions. Her oldest got two playing for John Carroll High. He seemed to recover within a week each time. But, she adds, “then my youngest Chris played in eighth grade and got a concussion and had a very hard time recovering. He was out of school for the whole second nine weeks, and finally went back in January after Christmas. He was still having a little bit of trouble, and he cannot play contact sports now, forever.”

When I ask whether there’s been any permanent damage, she responds pensively. “As far as we know … you know?”

Even so, she says the play-or-not-to-play decision isn’t easy.

“They’ve always begged to play football. If you knew they were gonna get hurt, of course you would never let them play. But you never know that … until you’re in the middle of it.”

Giraud, like Vicki Tuggle, sympathizes with parents who feel they’re flying blind.

“I did a lot of reading, once Chris got his concussion and he couldn’t — he had such a hard time recovering,” says Giraud. “I’ve really tried to educate myself. We also went to see a neuropsychologist, Dr. Joe Ackerson, a very well known authority in the concussion field.”

Dr. Ackerson, among other things, counsels concussion victims. His son has suffered several playing in football-mecca Hoover and for Sacred Heart University in Connecticut. He says football programs that better protect athletes’ safety usually have better records, too.

“The thing that makes the most difference in terms of reduction of concussions is proper technique, proper coaching, better rules and rule enforcement. That’s going to make more difference than the latest greatest technology, the latest greatest helmet, or anything you can purchase with money,” he says.

As far as treatment, which generally involves rest, he says there’s really no cookie-cutter approach because every brain and every brain injury is different. And that accounts for just one of the layers of uncertainty for parents. Anne Giraud knows it all too well.

“It is a dilemma,” she says. “You have to be educated. You have to know there’s a risk … you have to be prepared to tell them they can’t play. And I think that’s really hard for people.”

Vicki Tuggle sums up the dilemma with a confession of sorts:

“I say now that football is a lot of fun to watch … when your kids aren’t playing it. We’re big football fans — I’m just glad it’s not one of them on the field.”

Experts agree that if there’s even a chance your player has a concussion, he or she should be pulled immediately and checked out. But Vicki Tuggle also has some advice for after that, in the long term.

“Be patient, because the symptoms can last for a fairly long time,” she says.

Will chimes in: “Mmm-hmm. Take your time recovering.”

The Girauds, the Tuggles, Doctor Ackerson and his family — they’re all pretty much on the same page when it comes to protecting the body’s most important organ: education and patience are vital.

Chilean Smiljan Radić Clarke wins architecture’s highest honor

The Pritzker Prize was awarded Thursday. "In every work, he is able to answer with radical originality, making the unobvious obvious," said fellow Chilean architect and prize chair Alejandro Aravena.

El Niño is set to take hold this summer, driving up global temperatures

A potentially strong El Niño weather pattern will likely emerge this summer and persist through the rest of the year. The hottest years on record generally occur in years when El Niño is active.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

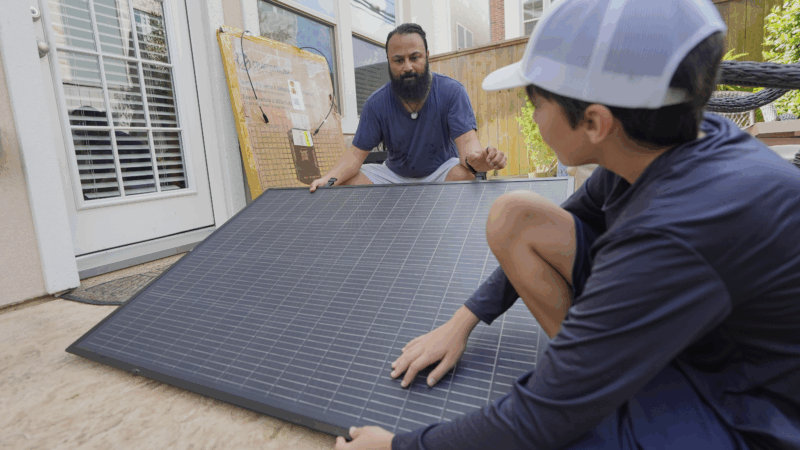

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.