Bilingual Ed in the South: Enormous Economic Consequences

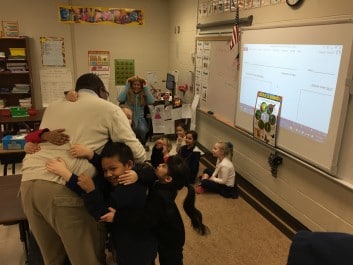

Some of Unidos Dual Language Charter School teacher John Rendon's second-graders getting into a lesson. Play the audio to hear what comes next. For more on Unidos, see Part One of this series, "It's Happening, Even at This School."

Students who don’t speak English as their first language – or “language minorities” – rank toward the bottom in almost every measure of academic achievement. Moral and legal concerns aside, even if their population were to stop rising, the situation signifies a looming hit to the national and regional economies. This week we’ve been exploring language-minority education in the South. The radio version of today’s final story starts with a simple elementary school lesson we hope you’ll try to follow. Listen above, or read below.

Imagine being in second grade and trying to learn math in a language that you’re also learning. That’s the situation for an increasing number of students in the U.S. and the South. If you focus too much on learning English — maybe in special, isolated classes where you don’t hear your peers speaking the native language — you fall behind in math, among other things. But you can’t learn those core subjects from a teacher you don’t understand.

“We put them into school and we say, ‘we’re going to start in a new language – you have no labels for any of these things that you already know,” says author and researcher Patricia Gándara of UCLA. “I mean, the most critical, important learning that occurs in a person’s life is discounted. It’s crazy.”

And those hurdles have increasing economic ramifications as language-minority students make up more and more of the school population of the South and the nation.

“Those kids, given the way we’re dealing with the situation now, are enormously high-risk for not making it in this society. That is going to convert into lower average level of education for the people in those areas,” Gandara says. “The economic consequences are going to be enormous, unless we figure it out.”

Baylor University economist Van Pham agrees. He adds that conservative estimates of the return on someone graduating from high school rather than dropping out are in the order of two dollars for every one dollar spent. And he makes another connection:

“In the labor market, there’s the ‘discouraged worker’ that leaves the labor force because they can’t find work. I think the phenomenon is similar here: these immigrants who are trying to learn the language on top of subject matter – it could get very hard. At some point, they don’t see the point, and they’re going to drop out.”

Language-minority students have some of the highest dropout rates in the nation; some estimates put the cost to the economy at several hundred billion dollars.

And there’s another more subtle connection – something that gets lost when these kids don’t learn the dominant language, something Pham lived when his family came over from Vietnam: He explains that in developing countries, where this has been studied more, having even just one educated person in a household makes the entire family more functional, more integrated into the economy. In the U.S., that role is often filled by a family member who speaks the dominant language. That relative lubricates older generations’ participation in the economy.

And there’s a counterintuitive concept to remember here, too. Margarita Pinkos, a longtime bilingual educator and former Director of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition, starts with a practical example.

“Let’s say that you are IBM, and you’re going to send one of your programmers to work in France,” she says. “And they don’t speak French. But they need to know the labor laws of France. What language would you teach them that in? In English! If you really want not to be sued, you want them to learn that in English.”

But people tend to reverse that logic when it comes to kids in school, maybe because it leads to that counterintuitive idea, which we covered earlier in the series: If you teach language-minorities their math, science, and other core subjects in their native language, in the long run they do better in school, including learning English. But parents, educators, voters, and policy leaders don’t necessarily know that.

Jason Mizell, who’s all of the above, does know it because he sees it with his students at World Language Academy, a charter school in north Georgia where Spanish-speakers and English speakers learn in both languages. He says of the school’s native Spanish-speakers, “they’re going to be able to speak English fluently – read it, write it, at a truly high academic level, but the same thing in Spanish. So it’s not like you’re sort of stripping away their language, but you’re actually building on top of what they already have, and helping them to keep growing.”

He says that should be the goal of all schools teaching language-minorities, “because otherwise you have these kids who graduate, who’re neither here nor there. They end up dropping out of school. Let’s be honest: if you’re not successful in school, you drop out. You look for something else. And a lot of times that something else is not what we want as a society.”

Speaking of that big picture, education leaders and advocates across the South are starting to think that, despite the politics of it, the steady increase in a population that’s consistently under-educated could push leaders to try different approaches. Even if it means putting stock in counterintuitive research findings over “common sense” that turns out not to hold up.

Team USA faces tough Canadian squad in Olympic gold medal hockey game

In the first Olympics with stars of the NHL competing in over a decade, a talent-packed Team USA faces a tough test against Canada.

PHOTOS: Your car has a lot to say about who you are

Photographer Martin Roemer visited 22 countries — from the U.S. to Senegal to India — to show how our identities are connected to our mode of transportation.

Looking for life purpose? Start with building social ties

Research shows that having a sense of purpose can lower stress levels and boost our mental health. Finding meaning may not have to be an ambitious project.

Danish military evacuates US submariner who needed urgent medical care off Greenland

Denmark's military says its arctic command forces evacuated a crew member of a U.S. submarine off the coast of Greenland for urgent medical treatment.

Only a fraction of House seats are competitive. Redistricting is driving that lower

Primary voters in a small number of districts play an outsized role in deciding who wins Congress. The Trump-initiated mid-decade redistricting is driving that number of competitive seats even lower.

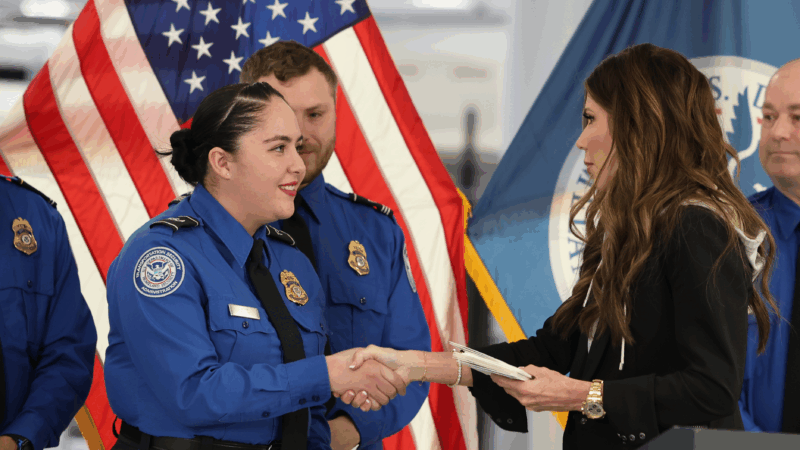

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.