Alabama Charges More Women for Chemical Endangerment of Children than Any Other State

In August of 2014, Casey Shehi gave birth to a healthy baby boy at Gadsden Regional Medical Center. But not long after, she was arrested for chemical engagement of a child. Shehi was confused at first, she says, until she remembered that she’d taken two anti-anxiety pills during her pregnancy, given to her by her then-boyfriend.

Shehi’s story is part of a growing trend. In the last few years, authorities have aggressively prosecuted women for prenatal drug use. A joint investigation by ProPublica and AL.com found that Alabama prosecutes more pregnant and new mothers for this than any other state does. Al.com’s Amy Yurkanin reported the story with ProPublica’s Nina Martin. Yurkanin tells WBHM’s Rachel Lindley how it all started.

Interpreting Alabama’s Chemical Endangerment Law

“The chemical endangerment law was originally passed in 2006 to address the issue of meth labs in people’s homes and the danger of exposing young children to the chemicals involved in making meth,” explains Yurkanin. In 2008 and 2009, a couple of prosecutors began applying that law to women who used drugs during pregnancy, saying that exposing an unborn fetus to chemicals or drugs is the same as exposing a born child to a situation where drugs are being manufactured.

“Those cases were upheld by the Alabama Supreme Court in 2013 and opened the floodgates for prosecutors who wanted to start applying this chemical endangerment of a child law to any woman who uses illegal substances during her pregnancy,” says Yurkanin.

This concerns many in the public health community.

“The fear is that women will not go see doctors if they are afraid that doctors will turn them in for using drugs during pregnancy and that they might end up in jail,” Yurkanin says. And since the law was written with meth labs in mind, Yurkanin says there are a lot of details left to the interpretation of individual law enforcement officials.

For instance, she says, the statute doesn’t say anything about legal prescription drugs. “Prosecutors will tell us that they aren’t going to prosecute a woman who’s on a legal prescription for painkillers, but technically they could.”

Consequences And Separation

From the beginning, Yurkanin says there were vast disparities in how Alabama counties applied the law to pregnant women.

“Take Birmingham and Jefferson County. We found two cases in the Birmingham office and Jefferson County’s D.A.’s office,” Yurkanin says. “Contrast that to Etowah County, where there were more than 30.”

Counties handle sentencing very differently, too. “A lot of counties really do concentrate on getting women into pre-trial diversion or drug court or treatment programs,” Yurkanin explains. But in other counties, women go straight to jail.

The children of these women generally end up in some form of foster care. She says these cases often lead to the separation of mother and baby.

“We bring up the Casey Shehi case, where it was maybe a couple doses of Valium,” says Yurkanin. “There was another case out of Crenshaw County, where a woman lost custody of her child for two and a half years.”

In that case, the woman was arrested in 2012. “For two years and a half years, this woman lost custody of her child,” says Yurkanin. “The mother claimed that she had a legal prescription for Lortab. The district attorney never disproved this.”

In 2014, prosecutors declined to proceed with the case, and the mother and child were reunited.

“That’s one of the consequences that can happen when this law is misapplied,” Yurkanin says.

Alabama’s Struggle With Newborn And Infant Health

Alabama has long struggled with the issue of newborn health and infant health. “I think this is an attempt to maybe improve some of these outcomes,” says Yurkanin.

“We have such high infant mortality rates and newborn mortality rates, but people with experience in public health have raised a lot of questions about this policy and are really not sure that this is the right way to go,” she says. “We’re using a law that wasn’t intended for this, so there are some unintended consequences, such as women who are being swept up in these cases, who probably don’t deserve to go to jail for what they’ve done.”

There are also looming questions about hospital drug-testing policies, including the issue of privacy, for pregnant women and new mothers. Yurkanin explains that hospitals weren’t very forthcoming with that information during the Al.com/ProPublica investigation.

“We surveyed about 49 hospitals that offer maternity services, and we received only seven responses back,” Yurkanin says. “We’re not entirely sure what the different policies are across the state, but it’s fairly clear that a lot of these women are coming to the attention of law enforcement through the healthcare system at some point,” Yurkanin says.

“That raises a lot of questions of the constitutionality of that; whether these women are giving consent to be drug tested. A lot of these questions are unanswered right now.”

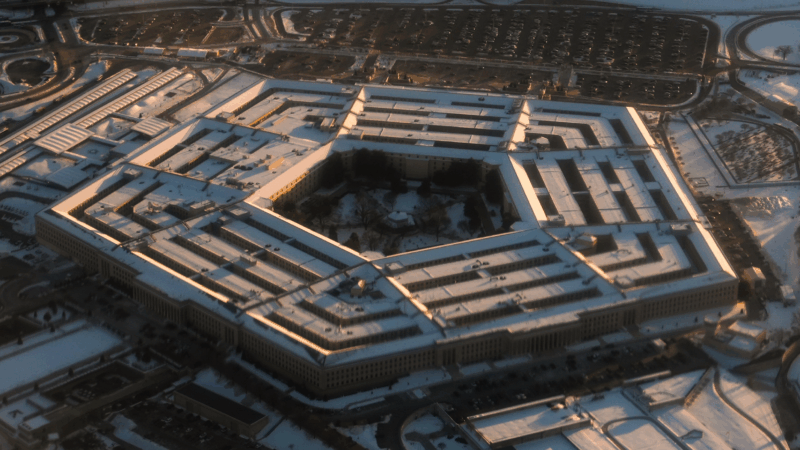

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

A new film follows Paul McCartney’s 2nd act after The Beatles’ breakup

While previous documentaries captured the frenzy of Beatlemania, Man on the Run focuses on McCartney in the years between the band's breakup and John Lennon's death.

An aspiring dancer. A wealthy benefactor. And ‘Dreams’ turned to nightmare

A new psychological drama from Mexican filmmaker Michel Franco centers on the torrid affair between a wealthy San Francisco philanthropist and an undocumented immigrant who aspires to be a dancer.