After Almost 100 Years, Birmingham’s Olmsted Park Plan Sees New Life

With the success of Railroad Park in downtown Birmingham, the City has seen increased support for more public green spaces. As the City develops new parks and trails for Birmingham residents, leaders are taking lessons from the city’s history, including seeking advice from a park plan published almost a century ago.

Along Birmingham’s 1st Avenue South, construction efforts are under way to transform an old railroad corridor into a greenway known as the Rotary Trail.

Cheryl Morgan, who helps facilitate the project, says the trail will connect Railroad Park to Sloss Furnaces. The Rotary Trail is the newest addition to the Red Rock Ridge and Valley Trail, a project that will link all of Jefferson County with 750 miles of user-friendly paths.

Morgan says the initiative adds green space and protects the city’s natural resources, but the idea is not new. She says the Red Rock Trail is largely inspired by a park plan published almost 100 years ago.

“We’ve begun to incrementally re-examine the Olmsted Plan for its wisdom, viability, and potential to create these things that are about quality of life and health and well-being,” Morgan states.

The Olmsted Brothers were nationally known landscape architects, famous for designing parks all over the country. In 1925, they published a park plan for Birmingham, known as the Olmsted Plan. It called to “protect the natural wonders and vistas of the city” by adding parks and greenways.

“Originally, if you follow their plan, it’s along our creek system,” says Denise Bell, Birmingham’s floodplain manager. She says the Olmsted brothers planned for beauty and recreation, but ultimately they saw the need to preserve the city’s watershed. “It’s purely along…what we would consider our floodway.”

Birmingham is in a valley, resting at the foothills of the Appalachians. The city’s creeks collect water running down from the mountains and filter it through the floodplains. The Olmsted Plan preserved these major tributaries, specifically those of Village and Valley Creek. Belle says this would have protected the natural flow of water through the city.

Zac Napier,Freshwater Land Trust

Rotary Trail is currently under construction. The project extends the green space of Railroad Park four blocks along 1st Ave N.

But, in 1925, Bell adds, local industry profited from these natural resources, and Birmingham did not follow the Olmsted Plan. She explains, “You had your steel plants and corporations who needed the water. And people needed to get to work, so they located close to the water without really knowing the risk they were taking.”

Belle says most of the people who moved to the floodplains were African American industrial workers. They built communities along Village Creek such as Ensley, East Thomas, and Pratt City. Years of development increasingly obstructed the path of water, which led to significant flooding.

From 1988 to 2007, the City stepped in to complete a series of buyouts to remove homes from these areas.

Many people had to relocate, including Marilyn Roberts of Ensley. Reflecting the flood events, she says, “One year when they had like 8 feet of water. My mom was asleep and woke up and the water was so high, they had to get the boats to go in to get her.”

Chris Hatcher, Birmingham’s Urban Design Administrator, says flooding in these communities forced the City to rethink its approach to development.

“You begin to think about, OK, now that we’ve got structures out of there, residents out of there, what are we going to do with it? Can we do something to make it an asset to the community? Boom! You’ve got what the Olmsted Brothers’ original goal of the plan was,” he explains.

Organizations like the Freshwater Land Trust are helping the city transform vacant buyout property into green space that joins the Red Rock Trail. Other sections of the trail include former mining sites and rail lines that now serve as parks and greenways. These properties were sold or donated by local industries after the land lost its value for mining iron ore.

Wendy Jackson, director of the Freshwater Land Trust, says Birmingham ignored its natural landscape for too long, but now is the time to return to Olmsted principles.

“We had this chance in 1925, we have the chance again to do this, and that was a message that resonated with the community,” says Jackson. She believes the Red Rock Ridge and Valley Trail is changing the face of Birmingham. She says it redirects the city’s industrial past and brings nature back into the urban environment.

“Every time we build a new section of Red Rock Trail, which is now connecting all these green spaces, people get reconnected to places they had forgotten about,” she says. “New energy is born.”

Birmingham may have been a completely different city had it followed the original Olmsted Plan. But with the opportunity to create its own version, the railroad tracks that built the city will now serve as the focal point for preservation.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

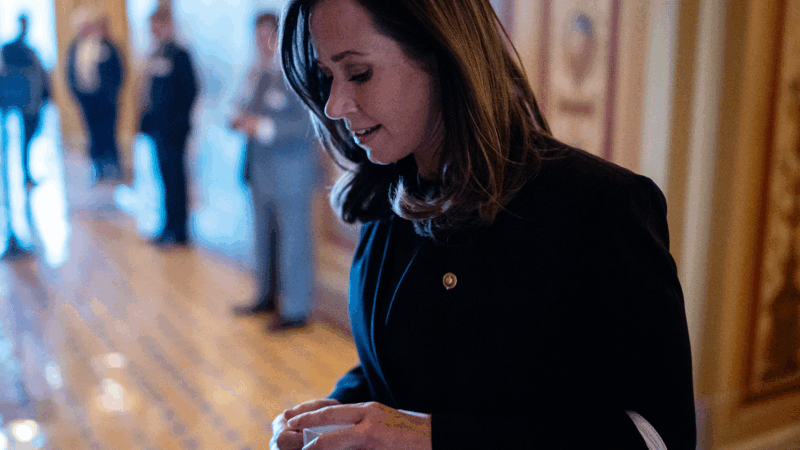

SNL mocked her as a ‘scary mom.’ In the Senate, Katie Britt is an emerging dealmaker

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.