Life After Prison: Ex-Felons Often Struggle to Find a Job

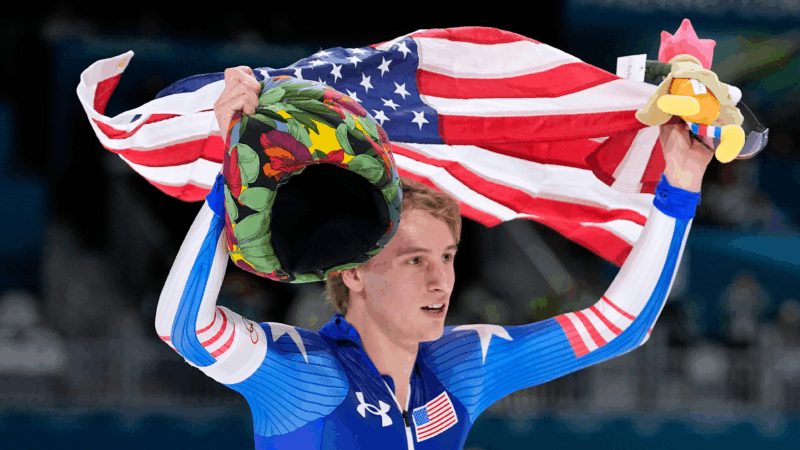

Juanida Pitts, left, and Melinda Ricketts, owners of A Cut Above the Rest Lawn Service and Landscaping, discuss a job with one of their employees, Michael Holly. All three are ex-offenders. Pitts and Ricketts make a point to hire ex-convicts to give them a chance to land on their feet after incarceration.

Throughout the week, WBHM is reporting on the hurdles ex-offenders face once they’re released from prison. One of the primary challenges they face is finding stable employment. In addition to the external struggles ex-felons face when looking for work, many also grapple with internal ones, like drug addiction or mental health issues. But, issues aside, ex-offenders need a job to provide for their basic needs, in addition to money required to pay court expenses and restitution.

The long path back to a normal life begins with whether or not an employer will give ex-offenders a chance.

On a hot Thursday afternoon in Huntsville, Alabama. A small landscaping crew – one man and two women – cut the grass in front of a hotel. There’s something special about this crew. All three have been incarcerated. Melinda Ricketts served two and one-half years at Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women on a drug charge. She says she was tired of being turned down for jobs because of her criminal record. So she started A Cut Above The Rest Lawn Service and Landscaping. And she makes a point of hiring other ex-offenders.

“Those are the ones that seem to work and stay working” Ricketts says. “It’s because they have a mark against them. So they have something to prove.”

Ricketts launched the company with Juanida Pitts, also an ex-con. Pitts leads workshops for her new employees, encouraging them to follow career paths and not just take jobs.

“I also try to instill the fact don’t bring that stinkin’ thinkin’ that you have in prison to the street,” she says. “Come out here, work hard, accomplish some different goals in your life and become a rehabilitated citizen for the state of Alabama.”

Not all ex-offenders are so lucky to have Ricketts and Pitts in their corner. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics study, only 12.5 percent of employers said they’d accept an application from someone with a criminal record. Tanya Dunn knows all too well how difficult it can be. She was recently released from Tutwiler after serving a five and one-half year sentence for check fraud.

“It’s not what they say when you tell them that you’re an ex-felon, it’s the whole expression on their face,” Dunn says. “You don’t have to say anything most of the time. And, so, needless to say, they never called me.”

With that attitude from employers, how can ex-cons ever make a smoother transition back into everyday life?

One idea is to change the standard application for jobs. Those usually have a box to check if the applicant has been convicted of a crime. Manuel LaFontaine, who served time in a California jail for a violent crime, is a member of All Of Us Or None, an ex-offender advocacy group.

“Ban The Box is a campaign that’s trying to reduce discrimination based on someone’s past convictions,” LaFontaine explains. “We recognize a background check may not be necessary for a job decision. We say that because most jobs do not involve unsupervised access to sensitive populations or handling sensitive information like a person’s bank account.”

Five states have banned the question on job applications, but Alabama isn’t one of them.

Overall, the problem won’t be solved without a major attitude shift from employers. Johnny Hardwick, a judge for Alabama’s 15th judicial circuit, says it’s a misnomer that once an inmate is released, he or she has paid their debt to society. As an advocate for ex-offender rights, he says, if no one will hire them, an offender’s debt is never paid in full.

“We don’t wear that red A these days. We use a bright color C for convict or F for felon,” Hardwick maintains. “And that knocks you out of a lot of things in society that you are perhaps able to do. We’ve got a lot of talent and skill wasting away in the penitentiary that we could put to work.”

When ex-felons get back to work, it decreases their chances of recidivism. Still, getting a job is not the end of the story. Ex-offenders may need to learn new workforce skills, or life skills like personal finance and anger

management.

But most of that can’t happen until an employer takes a chance and hires a former prisoner.

Jordan Stolz opens his bid for 4 golds by winning the 1,000 meters in speedskating

Stolz received his gold for winning the men's 1,000 meters at the Milan Cortina Games in an Olympic-record time thanks to a blistering closing stretch. Now Stolz will hope to add to his collection of trophies.

How the FBI might have gotten inaccessible camera footage from Nancy Guthrie’s house

Last week, law enforcement said video footage from Nancy Guthrie's doorbell camera was overwritten. But the FBI has since released footage as Guthrie still has not been found.

How to hone your ‘friendship intuition’

Friendship expert Kat Vellos shares tips on how to make a new friendship stick, including what to do together, how often to hang out — and what to do if the vibes just aren't there.

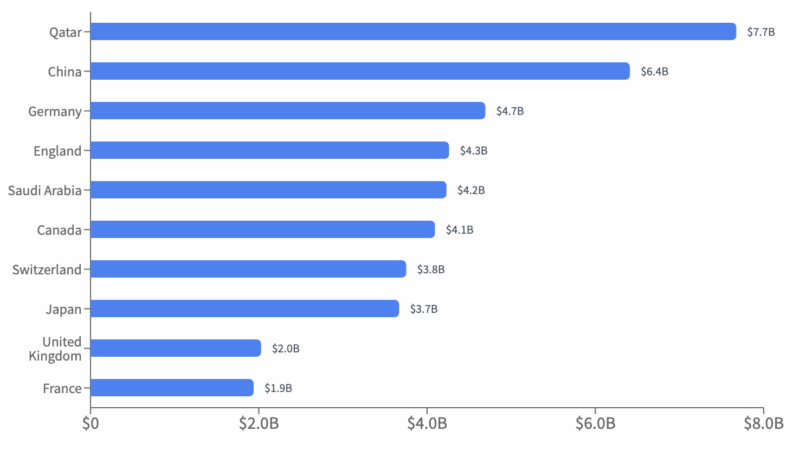

US Colleges received more than $5 billion in foreign gifts, contracts in 2025

New data from the U.S. Education Department show the extent of international gifts and contracts to colleges and universities.

Free speech lawsuits mount after Charlie Kirk assassination

Months after the killing of Charlie Kirk, a growing number of lawsuits by people claim they were illegally punished, fired and even arrested for making negative comments about Kirk.

Swing voters in Arizona say they want to see ICE reformed

Concerns about the tactics of federal immigration agents remain front of mind for some key voters who supported President Trump in 2024.