Cutting-Edge Forensic Research At ASU Could Help Solve Murders

Montgomery, Ala. — Believe it or not, in a healthy human body, microbial cells outnumber human cells by about ten to one. Scientists, doctors, and health-conscious people are learning more and more about our “personal ecosystems.” But what happens to this individualized community of life after we die? Some Alabama State University forensics researchers are looking at patterns, which could — among other things — help investigators solve murder cases. WBHM’s education reporter Dan Carsen has more:

Ten Alabama State University students take notes in a Crime Scene Investigation class. A projector screen shows gruesome photos of damaged bodies in various stages of decay. Dr. Gulnaz Javan helps the would-be investigators piece events together.

“What you can tell — the story?” she exhorts. “It’s very bloody, the shirt.” When several students begin to notice key details, she excitedly pushes them along. “Yes, exactly! Here, can you see fingers … he tried to rape someone.”

Javan is from Turkey but she’s worked in government and university labs around the U.S. She recently got a National Science Foundation grant to pursue a line of research so new it needed a new word: “thanatomicrobiome.” As the Greek roots hint, it means the living things in a body after that body dies.

Javan says previous forensic research focused mainly external factors. “My project is very different,” she adds. “I focus on the internal organs like liver, spleen, heart, brain, and if it’s possible, I can collect the blood.”

Basically, once we die and our immune systems stop working, the microbes living in us go to town. They multiply rapidly and spread to organs that had been relatively sterile. And as ASU biochemist Sheree Finley says, “There are unique microbial signatures at certain time-points during the decomposition stages.”

Finley is studying microbes in the soil underneath corpses. By “microbial signatures” she means the types of microbes present, as determined by their DNA. And this could lead to a new way for criminal investigators to establish what they call post mortem interval, or time of death. Right now, they can go by odor, body temperature, or even the life-stage of maggots. But soon they might also rely on the populations of microbes inside a corpse. That’s one goal of Dr. Javan’s two-year, $200,000 grant. It’ll pay for her and five students to study microbes from a hundred cadavers.

I meet the team in the lab as a machine they call “the beater” shakes vials of tissue and solvents so fast they blur. They’re identifying microbes in organ samples by extracting their DNA. As you might guess, forensics research is not always pleasant. When Javan started the work with cadavers, she stopped eating meat. The smells of refrigerated tissue samples — let alone 10-day-old bodies — are intense. (Be glad you can’t smell this story.) I ask Finley why she and others are attracted to this kind of work:

“Well this is quite fascinating, wouldn’t you agree?” she responds. “We think of death [as] there’s no more life. But actually there’s a lot of life in soil and in dead bodies. And if we

can tap into the activity and the abundance, we can actually use that to give us more information about death.”

Objective figures, including microbes counted by sophisticated computer programs, could help with that at crime scenes. “[With today’s methods] the investigator has to use his or her subjective opinions,” says Finley. “But when we look at the microorganisms, it cuts out the subjectivity of it, and we can actually look at data to determine the time of death.”

West Virginia University’s Suzanne Bell has been in forensics for three decades and this year was named to the first U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Commerce National Commission on Forensic Science. She calls Dr. Javan’s work “promising,” and says decomposition is so complicated that any new tools to determine time of death are welcome:

“It’s a really, delightfully complex process. And there are lots of variables involved in it, but this I think will help us sort some of those out. I think this is a good step in the right direction.”

This new step could help verify or contradict crime suspects’ stories. And Dr. Javan’s NSF grant is a new chapter in the story of this historically black university — it’s the first grant for ASU’s forensics department. Though that program is only four years old, the research raises a question that reaches back to the earliest humans: If microbes have evolved to be with us in life, then why not in death?

And the work could very well help answer the more specific question of how a person actually died.

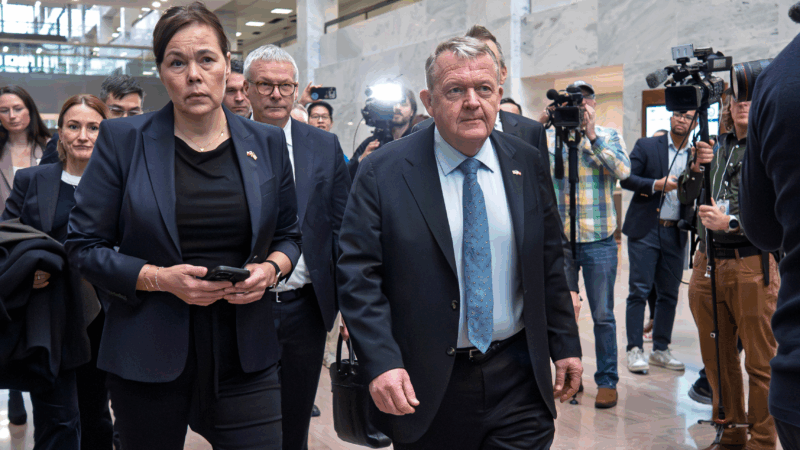

European troops arrive in Greenland to boost the Arctic island’s security

Troops from several European countries, including France, Germany, Norway and Sweden, are arriving in Greenland after talks between Denmark, Greenland and the U.S. on Wednesday highlighted disagreement.

More students are going to college. Affordability and workforce training are factors

Overall enrollment is up slightly at colleges and universities, driven by gains at community colleges and public four-year programs.

What Teddy Roosevelt has to do with Trump’s moves in Venezuela and Greenland

Presidents James Monroe and Theodore Roosevelt helped shape a policy that rationalizes U.S. intervention in Latin America and elsewhere. But Trump has brought that idea to a whole new level.

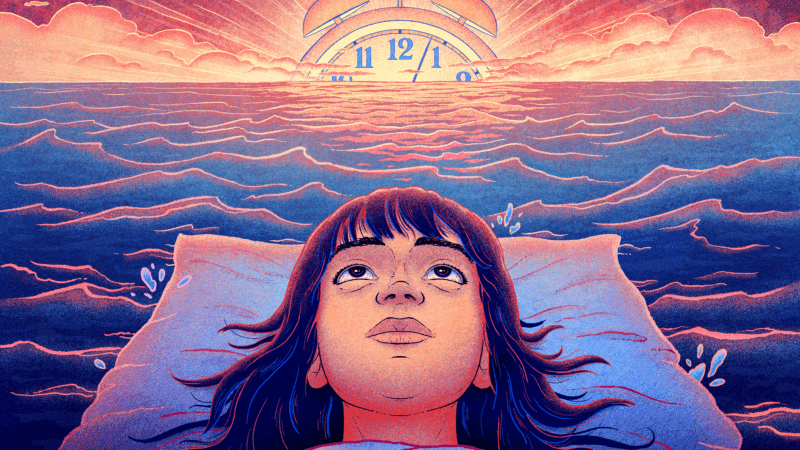

4 ways to beat the anxiety of insomnia — and get back to sleep

People struggling with insomnia tend to hyperfocus on the fact that they can't sleep, which can prevent them from getting any shut-eye. Experts share effective practices to overcome sleep stress.

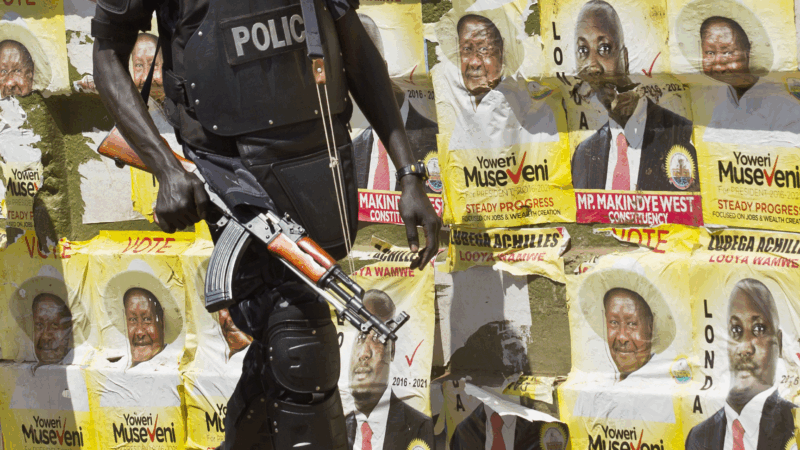

Uganda goes to the polls amid heavy security and internet blackout

Ugandans are voting in a tense presidential election as 81-year-old President Yoweri Museveni seeks to extend his four-decade rule amid an internet shutdown and heavy military deployment.

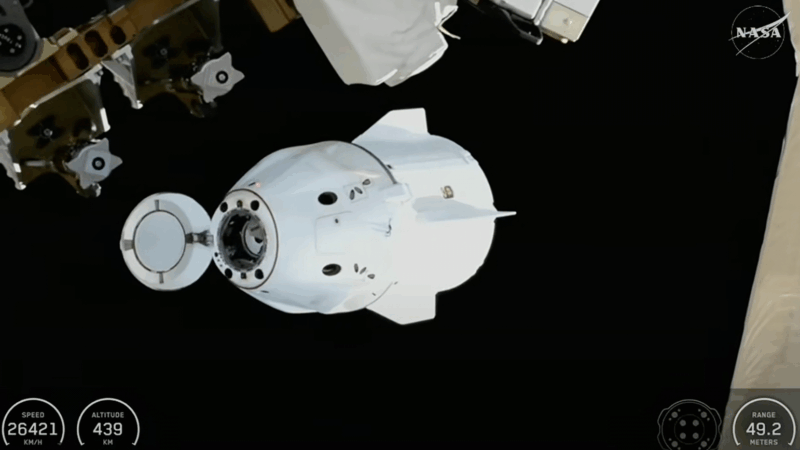

After a medical evacuation from space, NASA’s Crew-11 returns to Earth a month early

Four people from NASA's Crew-11 mission splashed down off San Diego successfully completing five months aboard the International Space Station. The trip was cut short due to a medical issue.