Birmingham Land Bank

Adrian Ward has fond memories of kids and families from growing up in Birmingham’s College Hills neighborhood.

She moved away and lived a couple of places. Then seven years ago she felt the tug of home and decided to move back to the street where she grew up — right across from her mother.

“When I told my family that I bought a house in the neighborhood, I did everything without telling everybody,” Ward said. “Somebody said, ‘I hope it’s not the house across the street.'”

Ward was a little embarrassed because it was the house across the street. Trees had fallen though the roof. It was not in good shape.

But a nine-month, total renovation later Ward had a 1930s home she loved. Her front porch has nice views of Legion Field and the downtown skyline. But the quiet neighborhood has a downside.

“Right now, across the street from me, next door to me, there’s just empty lots,” Ward said. “And that makes me said.”

For a neighborhood champion such as Ward, that’s meant calls to the city about overgrown weeds and calls to police about suspicious vehicles. Empty lots don’t help her property value. There’s still embarrassment.

“Sometimes you don’t want people to come into your neighborhood cause you don’t want them to have to pass those conditions because they’re like, ‘are they safe? Where does she live?'” said Ward.

What is a Land Bank?

“We wanna turn our housing communities and residential areas that have blight into prosperous communities,” said Jay Roberson, Birmingham City Councilman. He says one way to spur that turnaround is a land bank.

The Alabama legislature authorized the creation of a Birmingham land bank earlier this year. The city council is currently considering an ordinance setting it up.

This is how it would work. If a lot’s property taxes haven’t been paid for five years, and the land doesn’t sell at a tax sale, a land bank can acquire it. The land bank can then demolish, rehab, occupy or sell the property. City officials say as many as 4,500 lots in Birmingham could qualify.

Land banks have been around for decades, but Emory University law professor Frank Alexander says the discussion has particularly picked up in the last few years.

“The recent movement toward land banks is really a recognition that new tool is needed to be able to go after these abandoned properties and put them back into productive use,” said Alexander.

When owners walk away, properties are often “stuck” with back-taxes worth more than the value of the lot.

“So what we are doing with land banks is to unlock the inventory of property which is not accessible to the marketplace,” said Alexander.

He says with careful planning and input from community, lank banks can turn abandoned properties into housing, businesses or green space.

The Power of Land

Land banks though aren’t without critics. Audrey Spalding is with the Mackinac Center, a free-market think tank in Michigan. She studied the St. Louis land bank, which is one of the nation’s oldest. She discovered it kept acquiring more and more properties. Eventually as much as 10-percent of the land in the city was owned by the St. Louis land bank.

What was happening is land bank officials were refusing to sell properties because the buyers’ plans didn’t meet what the city wanted.

“The land bank can hold that property at hardly any cost, at hardly any repercussions and wait for what they hope to be a better offer,” said Spalding.

Meanwhile the property remained blighted. Spalding says such patterns have been observed in other land banks.

In some cases they’re a target for corruption. In May, Federal authorities arrested two employees of the Indianapolis land bank alleging they ran a fraud and kickback scheme.

“People underestimate how powerful it is to have control of land,” said Spalding.

Birmingham City Councilman Jay Roberson dismisses those concerns. He says he doesn’t believe the city will allow properties to just sit vacant.

Roberson hopes to have the Birmingham land bank in place by the end of the year, with a wave of neighborhood redevelopment to follow.

~ Andrew Yeager, December 17, 2013

Offshore wind developer prevails in U.S. court as Trump calls wind farms ‘losers’

A federal judge ruled Monday that work on a major offshore wind farm can resume, handing the industry at least a temporary victory as President Trump seeks to shut it down.

Minnesota officials sue to block Trump’s immigration crackdown as enforcement intensifies

More than 2,000 federal immigration agents are in Minnesota, and that number is expected to increase. On Monday, an NPR reporter witnessed multiple instances where immigration agents drove around Minneapolis — and in parking lots of big box stores — and randomly questioned people about their immigration status.

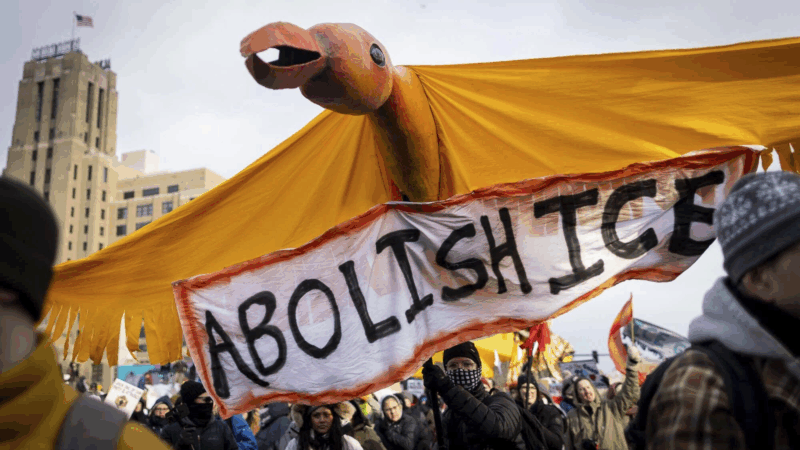

In photos: A week of protests against ICE

People across the country gathered to protest against ICE over the past week.

Elon Musk’s X faces bans and investigations over nonconsensual bikini images

After the social media app's AI chatbot started generating sexualized images of women and children, two countries have blocked it and several more have launched investigations.

Trump administration tells states to end ‘orphan tax’ on foster kids

There's a growing move to end what some call "the orphan tax" and stop states from taking benefit checks from children and youth in foster care.

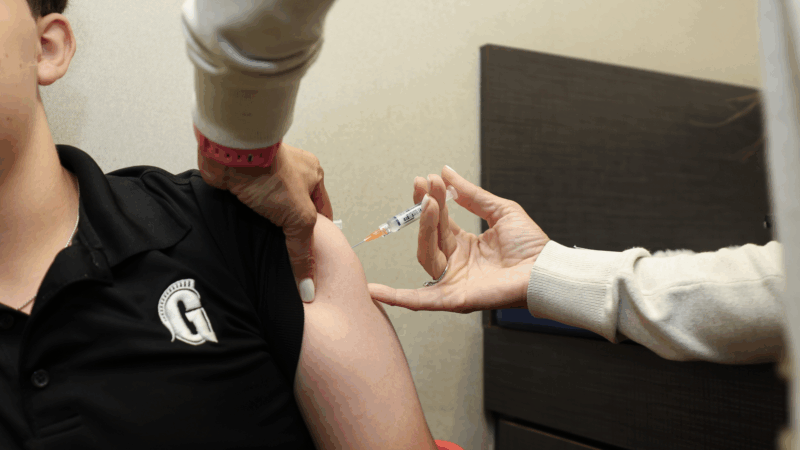

Flu shot recommendation for kids dropped just as the illness rages

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dropped its advice that kids get an annual flu shot at a time when flu cases and hospitalizations are surging.