Holiday Hunger: Harder To Address When School’s Out

Birmingham– Roughly 30 million students in the United States rely on federally subsidized school meals. Even so, more than half that number are in real danger of malnutrition. So many kids depending on school for food

Birmingham– Roughly 30 million students in the United States rely on federally subsidized school meals. Even so, more than half that number are in real danger of malnutrition. So many kids depending on school for food

may seem troubling enough … but what happens when school’s closed? Our Southern Education Desk reporter Dan Carsen has more on that deceptively simple question as districts across our area prepare for the holidays:

Rachel Price works full-time at a daycare center in Birmingham. She’s a single mother and makes

minimum wage, so she has full-time worries about feeding her children and grandchildren. Ironically enough I caught up

with her on her lunch break. As we stood between the squat brick building and a main thoroughfare, she confided,

“It hurts as a mother, tryin’ to tell your child they can’t go into the kitchen and get something.

It’s definitely a struggle. I have a lot of sleepless nights. I cry a lot.”

That’s because of practical details many of us don’t have to sweat. But for Price, the “little” things get

big, quickly. Like at the supermarket, or on her kids’ doctor visits:

“A lot of times you sit and you wonder, ‘Am I going to have enough? Do I go with

cheap, you know, do I go with noodles and sandwiches, or do I go with healthy meals?’ I

have had [my kids] where their iron was low, because I chose to go the noodle route.”

About 17 million food-insecure children across the country face these kinds of tradeoffs, and far more than that

depend on school meals for the bulk of their nutrition … but what happens when school’s closed?

“A lot of them do go hungry,” says Karen Kapp, director of Better Basics, a United Way children’s literacy and enrichment program

serving much of Alabama. She says as kids’ brains are maturing, the ones who aren’t getting enough

food can fall further and further behind.

Linda Godfrey, a nutrition and foodservice consultant, used to run summer-school feeding programs.

She’s seen the need firsthand. “Sometimes,” she says, “at six and six-thirty in the morning, they would have their faces to the door. And as

soon as the doors would open at eleven o’clock, they would already be lined up, and they were extremely

hungry. Especially on Monday.”

Children regularly fall through the cracks between school, food stamps, and community or church food

banks. A recent national survey found three in five teachers regularly see hungry

students.

At Hillview Elementary just north of Birmingham, curriculum specialist Tammarra Tippett helps run summer school, which includes

meals. But she sees teachers step in year-round.

“I do have teachers who send food home with their students over the weekend or provide

an extra breakfast snack out of their own pockets,” she says, adding, “They care about the kids and they know you can’t

learn on an empty stomach. You can’t get the results.”

She’s not just talking about test scores. Hunger increases the chances of academic failure, which

statistics show pushes people toward unemployment or even crime. Research also links malnutrition to

short-term and long-term health problems.

School systems and communities do have programs to get food to needy kids during breaks, but

frequently funding is short and guardians can’t manage the logistics. Summer programs especially rely

on centralized feeding sites, leaving carless rural kids hungry. And of course there’s pride. Food-service

expert Linda Godfrey offers more perspective:

“I had children that would come up to me and say, ‘I really don’t want to be out of school for

Christmas, because we know we’re not going to get much to eat.’ We can say over and over and over it’s

a parent’s responsibility to feed their children. But the bottom line is, they don’t.”

Rachel Price has perspective of her own. She knows lots of parents like her, working full time but not making enough money for heat,

transportation, and food. She says she used to refuse help, but one Thanksgiving she broke down and

accepted a food basket from her kids’ elementary school.

“I’ve been fortunate enough to have organizations that have helped,” she says. “So if you find yourself in a

situation where you need help, don’t be too proud to ask for it, because it’s not about us as parents. It’s

about our kids.”

But even swallowing pride doesn’t guarantee enough nutrition for needy children. When school’s closed,

some rely on a patchwork of programs that varies greatly depending on where they live. But many just

go hungry. And that has ramifications not only for their futures, but for the rest of us.

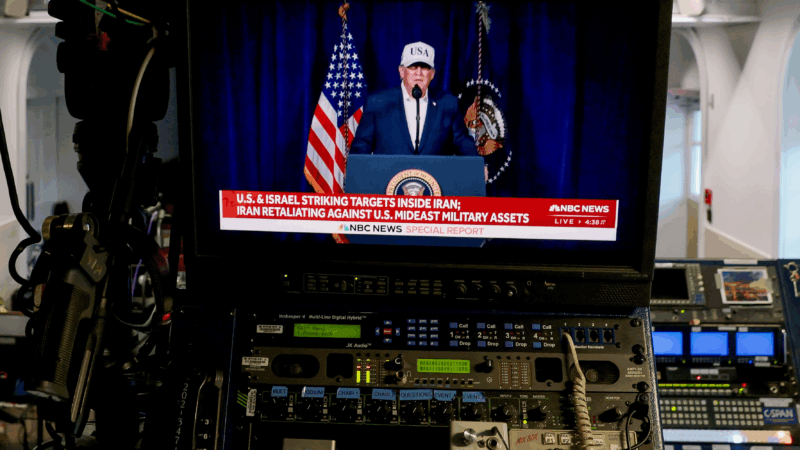

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed in Israeli strike, ending 36-year iron rule

Khamenei, the Islamic Republic's second supreme leader, has been killed. He had held power since 1989, guiding Iran through difficult times — and overseeing the violent suppression of dissent.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.