Civil Rights Pardons

Birmingham Mayor Larry Langford has issued a blanket pardon to those arrested in the city during the 1960s civil rights protests. Some 2,500, including children and the Reverend Martin Luther King Junior, were jailed during that era of fire hoses and police dogs. But as WBHM’s Andrew Yeager reports, the move seems more about reconciling the past than altering the record books.

Carol Jackson-Walton calls herself an activist. She sits facing a podium and arc of chairs in a library meeting room, waiting for the start of a city council candidates forum. It’s civic participation that’s far less intense than in 1963 when Jackson-Walton suspended her college career to march on the streets of Birmingham. She says police would round protesters up and take them to the courthouse.

“We looked up on the screen. And I said, I was the first person to see their face up there and I had a number. That’s when it became real to me. I have a criminal record.”

That criminal record would grow, as she and others fought a city leadership intent on maintaining segregation.

“I can remember going to jail once. We stayed one night. The next time was two nights. The next time in jail three. Four and then there was one time. I know I was in there an entire week. When I count it all up, maybe 15 or 16 times or more.”

Jackson-Walton’s record could be changed thanks to a blanket pardon issued this week by Birmingham Mayor Larry Langford. It would allow anyone convicted of protesting the city’s segregation laws to apply for a pardon. Langford, who faces a federal bribery trial later this month, says the idea came after a reporter called the city asking if Birmingham had ever issued pardons for civil rights protestors. The city hadn’t. Still the mayor doesn’t expect people to start lining up.

“Because to many who suffer during that era, it’s a badge of courage and a sign of the struggle.”

Three years ago, Alabama passed a law which offered a similar pardon. But a spokesman for the state parole board says just a single person has applied for one under that law. So even though the action may not mean much work for record keepers, Langford says the move is important for healing, as the city says, “I’m sorry.”

“Sometimes an apology does more for the person extending the apology than it does for the person receiving it.”

Former U.S. Attorney Doug Jones successfully prosecuted two former Ku Klux Klansman for the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church. He says the pardon doesn’t just right a wrong, it sends a message.

“Just as with the church bombing cases, Mr. Mayor, justice delayed does not have to be justice denied.”

For many protesters who were arrested, people like Myrna Carter-Jackson, they appreciate the gesture. But she doesn’t feel the need to seek a pardon.

“But pardon us for what? What did we do that we need to be pardoned? You pardon people when they’ve done something wrong. So I don’t remember being a party of something wrong.”

And now, neither does the city of Birmingham count any wrongs.

Camp Mystic parents from Alabama seek stronger camp regulations

Sarah Marsh of Birmingham, Ala. was one of 27 Camp Mystic campers and counselors swept to their deaths when floodwaters engulfed cabins at the Texas camp on July 4, 2025. Sarah’s parents are urging lawmakers in Alabama and elsewhere to tighten regulations.

Court rebuffs plea from domestic workers for better pay and respect

They're often paid low wages and lack job protections. A petition to the country's supreme court to support their demands did not see success — and they are protesting.

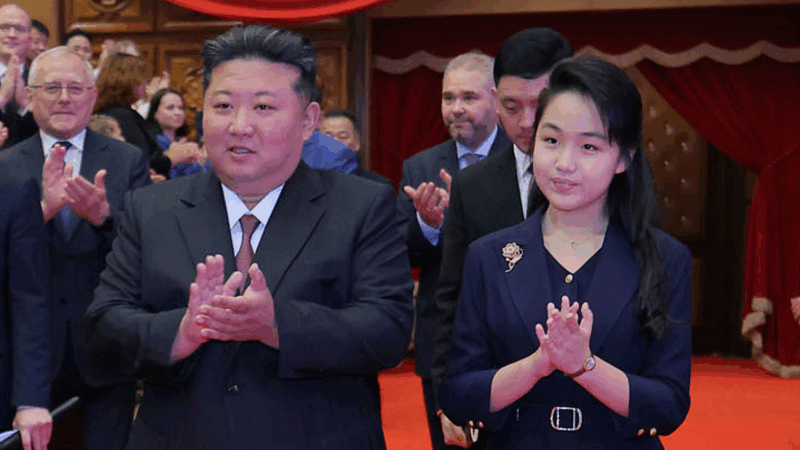

Spy agency says Kim Jong Un’s daughter is close to be North Korea’s future leader

Seoul's assessment comes as North Korea is preparing to hold its biggest political conference later this month, where Kim is expected to outline his major policy goals for the next five years.

Using GLP-1s to maintain a normal weight? There are benefits and risks

Drugs like Zepbound and Wegovy are intended for people who are overweight. Some patients are using them after bariatric surgery to keep pounds from creeping back. Others may just want to lose a few pounds.

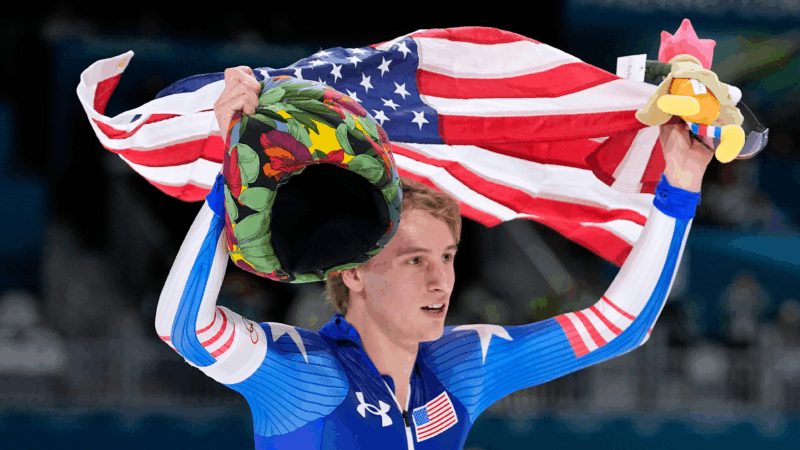

Jordan Stolz opens his bid for 4 golds by winning the 1,000 meters in speedskating

Stolz received his gold for winning the men's 1,000 meters at the Milan Cortina Games in an Olympic-record time thanks to a blistering closing stretch. Now Stolz will hope to add to his collection of trophies.

How the FBI might have gotten inaccessible camera footage from Nancy Guthrie’s house

Last week, law enforcement said video footage from Nancy Guthrie's doorbell camera was overwritten. But the FBI has since released footage as Guthrie still has not been found.