Considering Faith: Prayer in School

It’s 28 degrees, and one wonders what it is that can possibly lure 20 teenagers out of their warm beds and into school well before classes begin. Here in the Chelsea High School auditorium, a few students holding notecards take turns below the stage. When they pray, it’s not the hasty dear-God-if-you-help-me-ace-this-math-test-I’ll-never do-wrong-again kind of prayer. They pray for their fellow students, for their teachers, for each other.

Jake Epperson leads this sermon. He’s a junior, and has been a member of First Priority since middle school. Officially, First Priority is a club for Christian students to network. They’re known for their annual See You at the Pole rallies, where students pray around a school flag pole.

The Chelsea gathering is one of hundreds of First Priority meetings happening at schools year-round across the state. About 20,000 students get together weekly and pray in school.

First Priority began in Birmingham in the early 1990s after a Supreme Court ruling upheld students’ rights to form non-curriculum clubs at school, including religious ones. Now there are First Priority clubs across the country. Greg Davis is president of the Alabama chapter.

“Our mission is to help students share God’s love with other students. We want to be able to help students live out their faith, and to really do the things that the Bible talks about, do the things that Jesus did, try to help people, be kind to people, bless people, pray for ppl, encourage people.”

There are other religious groups for students. There’s the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and at Hoover High School, a club called Iqra for Muslim students. But none is as far-reaching as First Priority. The Alabama group has a $700,000 budget. And they are aggressive. First Priority keeps a “salvation report”, essentially a tally of students who have been saved at various schools. Jake Epperson remembers the first time he showed up for a meeting.

“It was kind of odd because I’d never talked about God in school before. So to go into a club where that’s all they talked about, it was really interesting, I liked it.”

Even more interesting is that Jake and other First Priority members see themselves as young ministers guiding their schoolmates toward salvation. And they can be persistent.

“Every morning we always walk around, I get here early, and we walk around and try and invite people. Sometimes they just say OK and they get up and come, and sometimes they say no I’m too tired, or I have to do homework or something. But you know one week they’ll come, so.”

At times, though, persistence gives way to pressure. And Greg Davis says there’s nothing wrong with that.

“Do we not think that kids get a lot of pressure to do drugs? To start drinking when they’re 14, 13 yrs old? They get a lot of pressure. It’s strong. Or to have sex when they’re not ready to have sex, before they should be having sex? Sure. There’s a lot of pressure. And so, my mindset would be if we could exert some pressure the other way to not be involved in those things, then maybe we can balance it out.”

“When I was first invited, I thought what’s the harm. May as well go to get them to shut up, to um, just see what it’s like. ”

Scout O’Beirne is a sophomore at Hoover High School. She was in middle school when a friend invited her to join First Priority. Since then, many more invitations followed.

“Kids would ask me all the time to come to First Priority…more in middle school than anything when I was, people were still finding out, like now it’s kind of accepted, Oh that’s Scout, you know, she’s different, she’s a liberal, she’s not Christian, that kind of thing.”

Some are less forgiving.

“I mean, I’ve had people hint at the fact that I’m going to hell because I’m not Christian. I’ve had people say you know, it’d be a good thing for you to be saved.”

Chelsea High School Principal Jay Peoples says it’s great that students bring their religious convictions to school.

“Because it makes the experience a lot richer and a lot more authentic.”

But he says things can get sticky if a school seems to endorse one religion over another. On the other hand, Peoples says, students are entitled to free speech. And the law says it’s OK, provided the activities are student-led.

“Now if a teacher were imposing that on a class per se, or if a student were taking advantage of a gathering and no one could leave and everyone was being forced to hear something, then maybe that would be a little bit different. ”

Back in the Chelsea auditorium, Jake Epperson and his classmates join together in a song. They’re swaying, their eyes are shut, bed heads bowed. A few arms are up in the air. Epperson says some of his friends say outright that they want nothing to do with salvation. And so he’ll drop it. But not for long.

“Eventually I may bring it back up, and then they may be more open to talk about it, they may say the same thing. But if I don’t try, I’m not doing my job as a Christian.”

And soon enough, they gather their things, and they’re off to first period.

~ Gigi Douban

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

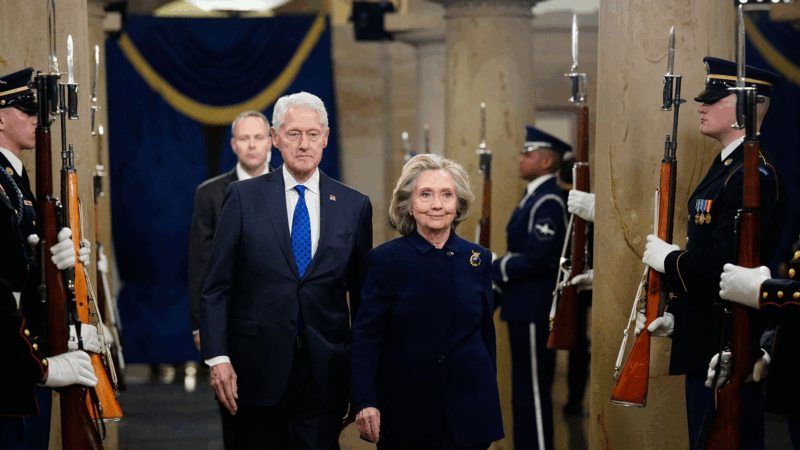

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

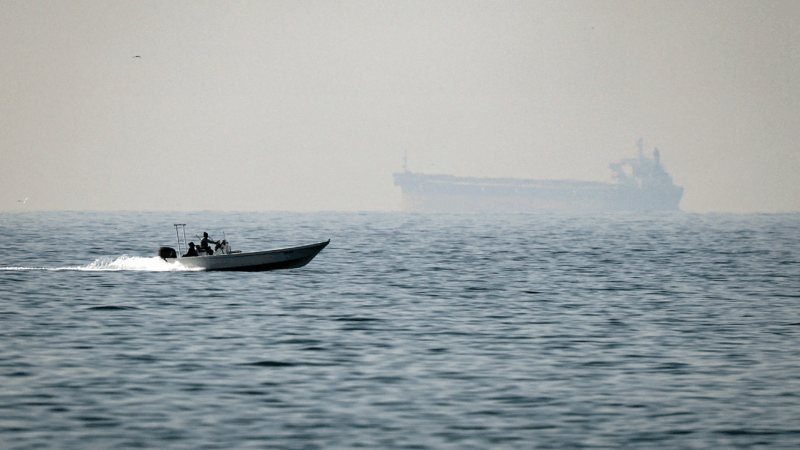

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.