SFS: By the Numbers

It’s three o’clock on a Saturday afternoon. The Walmart off Parkway East

in Roebuck is bustling with holiday shoppers. The parking lot is full. Customers filter in and out of the store joking, talking and relaxed.

But at night, it’s totally different. A security vehicle patrols the lot. The few cars there are park close to the store. As he loads bags into his car, customer Keith Turner says he knows why.

“I’m a lot more comfortable during the day than at night here. I will come out here at night, but I want to make sure I’m paying more attention because things tend to happen at night, and here I think it’s a little more ample for something to happen in this area, versus some of the other areas where the Walmarts are located.”

Perception of crime is often shaped by city rankings, and all the bad

publicity they generate. But are these “lists” reliable – or as irrelevant as Mr. Blackwell’s Best and Worst Dressed List?

Any discussion on crime statistics begins with the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the FBI. The Association developed The Uniform Crime Reporting Program in 1929 — it defined crime categories, such as homicide, murder, rape, robbery, burglary and automobile theft. A year later, the FBI began collecting, publishing, and archiving those statistics. Tom Bush is assistant director of the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

“It’s basically to assess and monitor the nature and the type of crime in the nation. But, it’s also to generate this information back to the law enforcement community, as well. So, we do use it and publish the information for us to track it, but it’s also a great benefit to actual producers of the information.”

That’s because the FBI uses the data collected from nearly 17,000 law enforcement agencies to compile the “Uniform Crime Report” and publish “Crime In The United States.” This Bible of American statistics is the official record for crime rates in the country.

Here’s the math lesson – and why it’s important. A city’s crime rate is the

number of crime victims divided by the city’s population. That equation ignore some factors that can drastically affect a city’s crime rate. For example, someone visits Birmingham from Atlanta and robs a house. The crime victim is now part of the equation. But, the fact the criminal was just “visiting the city” is ignored. So, the number of crime victims increases, but the city’s population doesn’t. This can skew the crime rate and make it “seem” worse than it is. The FBI’s Tom Bush says the crime rate also doesn’t consider “hot spots” or specific neighborhoods of a city that are more prone to crime or “hot” times of the day when crime is more likely – like late Friday night.

“You don’t get a full picture of the area just based on this data. It’s incomplete. It’s summary data, at best. You’ve got so many variables that come into play on that, all kind of demographics, events,the climate, movement of population. So, if you don’t take those things into consideration, and you look purely at these numbers, I just think it gives a very slanted outcome.”

There’s also the issue of “dark figures.” That’s the number of cases that

aren’t included in the statistic. University of Delaware criminologist Joel Best says many crimes go unreported because victims don’t trust the police or they know the person who committed the crime and are afraid of reprisal.

“I think most criminologists believe that the figures we have for murders are pretty accurate, because murders produce a dead body, they’re relatively easy to count. So, probably those numbers aren’t too far off. But, most other crime statistics have a substantial dark figure, and we can’t even guess how large the dark figure might be.”

John Sloan agrees. He’s chair of the Department of Justice Sciences at UAB and he says the Uniform Crime Reports should not be read as gospel. He says in the late sixties criminologists discovered some police departments doctored the books.

“What they were doing, they were reclassifying rapes as assaults, so there were fewer rapes than there actually were.”

Sloan says two other reports paint a far more accurate picture. First, there’s Self-reports, where authorities ask criminals and juvenile delinquents if they committed certain crimes. Then there’s the National Crime Victimization Survey or NCVS. Each year, it takes a national sample of households and asks if residents have been victimized. If so, did they contact the police? If not, why not.

“In my opinion, the best source that is current, is the NCVS because regardless of whether you reported the offense to the police, or not, you still show up in the NCVS. ”

But, he cautions:

“There is no best measure. There are different measures, which answer different questions that relate to the bottom line question of how much crime is there.”

“Black figures.” Inconsistent reporting. It’s no wonder criminologists rail against those who use these figures to rate the safety of cities. Joel Best at the University of Delaware believes people tend to concentrate on anecdotal evidence, like sensationalized news reports of particular crimes, and ignore the facts, no matter how they’re presented.

“One of the most interesting trends in criminology is during the 1990’s, the crime rate has dropped a great deal, and has remained relatively low. We have a relatively low crime rate, right now. And, yet, I think that most people assume that crime is actually at record highs.”

He’s right. An unscientific sample of people in Homewood confirms it.

Man #1 “It’s going up, there’s a murder every day”

Male #2 “Crime is going up because the Birmingham police aren’t doing their

job.”

Again, criminologist Joel Best.

“So, they’re really not paying attention to the crime statistics.”

It’s natural to assume that numbers tell the truth. But, it was Mark Twain

who said, “Facts are stubborn, but statistics are more pliable.” Words worth remembering the next time an annual ranking of the “the most dangerous” hits the media.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

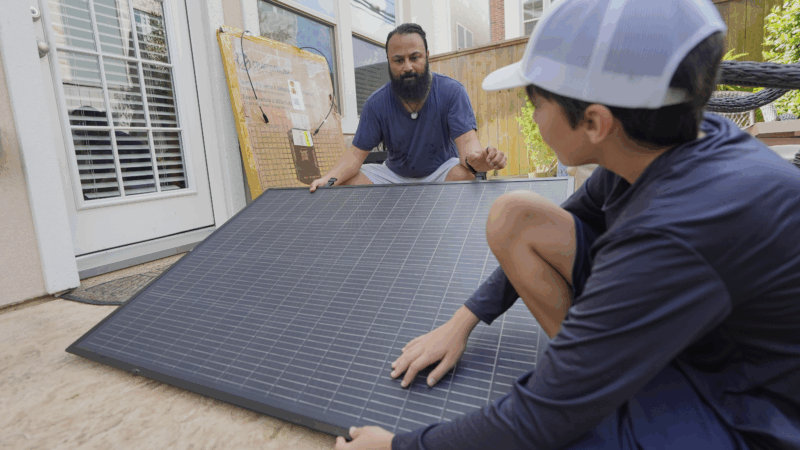

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.